Add a little optical illusion to the basic utility storage credenza concept and you have Rocky, a sideboard of sorts that stretches classic cabinetry geometrics into a perspective-challenging third dimension.

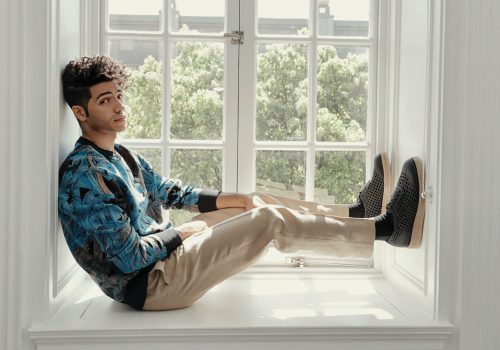

Born in Beirut but based in Paris and as passionate about graphic design as he is about furniture or lighting, Charles Kalpakian’s designs sit at the junction of several different overlapping worlds.

A quote from Gibran. A vase called ‘Saida’. A room divider called ‘Hawa’. A light fixture entitled, ‘Travail sur le Cèdre du Liban’. If his surname hasn’t already suggested as much, in the opening moments of our chat, it becomes clear that Charles Kalpakian may live and work in France but his roots are firmly in the Middle East.

Born in Beirut and brought up in Bahrain and currently sharing a workspace with a collective of fashion designers, artists and graphic designers in Paris, Kalpakian thinks of himself and of his work as a kind of ‘bridge’ between France and the Middle East. While the idea of acting as a bridge between cultures is neither new – nor for that matter confined to the Middle East and Europe – Kalpakian’s take on his self-appointed role is somewhat different. Rather than represent one side or the other, he takes aspects of both and blends them to create something new. And contemporary.

“I try to re-appropriate Orientalism,” he says, in response to my question about where he places himself on the design map. “We are heavily influenced by Western design and I like it myself but there is also something very beautiful about the way people live in the Middle East, even though I’m sure it has changed a lot, too.”

And so, simple and graphic, the bold but graceful lines of his work contain within them echoes of the Middle East’s calligraphic past and Europe’s Minimalist present. Or should that be the other way around? For while it is often forgotten, Europe has its own rich calligraphic present and the Middle East its own well-developed Minimalist past – after all, the father of modern architectural Minimalism, Le Corbusier, made no secret of the fact that his approach was influenced by an appreciation of the vernacular architecture of the Maghreb.

“When people [in France] think of Middle Eastern graphic, they think of something very ornamental, jewel-like, very crafts-oriented. I try to give a new sense, I take its essence and work with that.”

Shadows, a three-dimensional lighting panel intended to be hung on the wall, is an excellent example of that approach. Composed of a series of differently angled, semi-overlapping rhomboids, it casts both light and shadow light across its surface in a way that suggests both installation and an ultramodern take on the musharabiya, stripped though it is of any overt cultural appurtenance.

The bridging aspect of Kalpakian’s professional identity is not restricted to cultures, it also applies to disciplines. Projects in graphic design, architecture, lighting design and typography in his portfolio appear alongside object and furniture design, making him both multidisciplinary and multicultural. When his parents ran an advertising agency and his grandfather was a woodworker, design influences as he grew up were obviously quite varied.

Jar is a family of vases, also designed for Dar en Art

Another major influence – a logical outgrowth of his fascination for calligraphy – was street art and it was here, rather than on-screen or in the workshop that the designer first began to experiment with ideas as a teenager. For a while, he was quite taken with graffiti’s possibilities but eventually, he became frustrated by its two-dimensional nature and applied his interests to objects instead. Or at least to two-dimensional surfaces that have a three-dimensional aspect – an ongoing project to design a contemporary carpet for an Armenian-Lebanese dealer in Paris is based on the kind of impossible, cyclical and never-ending staircase Escher introduced into the popular consciousness in his lithograph, Ascending and Descending.

“For me,” the designer explains of his tail-chasing, Ouroboros-esque pattern, “that describes exactly the relationship between Europe and the Middle East.”

Whether Kalpakian has chosen his hybrid approach for himself or has had it forced upon him – less open than the British, he says that the French are still very focussed on ‘European’ design and that he isn’t really seen as a ‘French’ designer – is debatable.

Still, if being identified as a ‘Middle Eastern’ designer is a cross, it’s one he doesn’t seem to mind bearing, adding cheerily that while he may have been placed in a niche, the positive side is that those who approach him know who he is and what they want. While it might be limiting, being identified in France as a ‘Middle Eastern’ designer hasn’t hurt his career, as the young designer’s collaborations with assorted European design houses, amongst them Habitat, Dar en Art and Nemo-Omikron and the Marais-based contemporary design gallery, Galerie BSL, attest.

So what, I ask him, about coming home? “I do want to come back or at least, to work more in the region and I have been in touch with Carwan Gallery in Beirut about doing something. But I want to gain as much experience as I can here so that when I come back, I can do something really big. But you know, if there’s anyone reading this who’s interested in working together, tell them to get in touch.”

RIGHT: Functional art, Wall Shadows Lighting for Italian lighting specialists, Nemo Omikron, embeds LED lamps in a 3D panel to create an interplay of light and shadow, both illuminating and sculptural. LEFT: Formed from metal and evoking the symbol for Lebanon, the Cedar floor lamp functions as both a light and screen.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Paris Se Quema