Founded just four years ago, Tinder has launched a slew of offshoot platforms – including the exclusive and secretive Tinder Select – and has forever changed the game of love. Like many good love stories, this one begins on a night out. It is spring 2012, and a group of young men sit hunched around a table in Cecconi’s, a ritzy Italian restaurant on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. They are smart, good-looking, and on the hunt for women. They bend studiously over their phones, frantically texting girls they know, to see if they will “hang” with them for the evening.

Founded just four years ago, Tinder has launched a slew of offshoot platforms – including the exclusive and secretive Tinder Select – and has forever changed the game of love. Like many good love stories, this one begins on a night out. It is spring 2012, and a group of young men sit hunched around a table in Cecconi’s, a ritzy Italian restaurant on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. They are smart, good-looking, and on the hunt for women. They bend studiously over their phones, frantically texting girls they know, to see if they will “hang” with them for the evening.

Two metres away is a table of young women, also on a night out. One of the men clocks them. He has dark, intense eyes and fast, excitable hands. Perhaps, he suggests to his friends, they should try talking to these girls instead. The bolder members of the group approach the women. They then do what young men across the world have been doing for centuries – the agonising courtship of small talk.

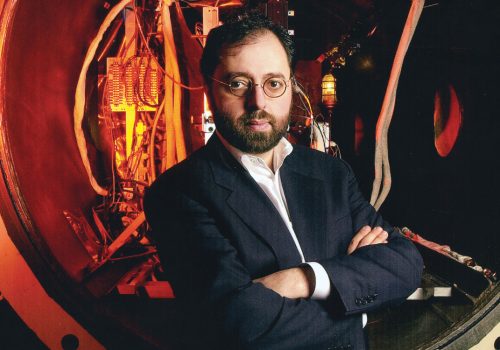

Sean Rad, the 30-year-old CEO of the dating app Tinder, laughs when he tells me this story. We meet over lunch in a small, unpretentious café off Oxford Street in London. He orders ginger tea and honey, because he tells me, he is “sick”. Some sort of cold/flu/temperature thing that he just can’t shift.

“I was like, this is comical! There we were sat in a restaurant all on our phones texting girls to see who would come out. But when I looked around there was a table of girls right next to us!” He takes a sip of tea. On one wrist he wears a chunky gold Audemars Piguet. On the other, three ‘intent’ bracelets made of string, the sort of thing students come back with after a gap year. One reads ‘Dream’, the second, ‘Power’. The third one simply says, ‘Breathe’.

If you’re single, under 35 or have children of a consenting age, you will be familiar with what Tinder is and what it does. If you’re not, these are the basics. Tinder is essentially a location-based mobile phone app, whose icon – a small red flame – can be found on the phones of single (and sometimes not so single) men and women across the world. Users open the app, get presented with an ever-revolving carousel of cheery/pouty/Blue Steel headshots and start swiping. Swipe left to reject and right to give the nod. A conversation is only initiated if both users right-swipe. It’s called “a match”; the digital equivalent of saying, I fancy you, you fancy me, let’s get this thing moving. Now a whole generation of men and women need never know what it feels like to be rejected.

For the record, I’m not a Tinderer (to tinder is now a verb). I’ve been out of the dating game since 2002, but I work with an office full of young, single men and women. They have all used Tinder. Even when not using the app they speak in a strange language of “right-swiping” (as in, “I’d right-swipe him”) and of mystifying maladies such as Tinderitus (like RSI, but for your index finger, after over-zealous swiping).

Some say Tinder has revolutionised the dating scene, facilitating introductions (or, as they’re called in Tinderland, “connections”) that would not ordinarily happen. Others say it is a “hook-up” app; the scourge of modern love, making empty one-night sex as easy as, well, swiping right. A Vanity Fair journalist wrote about “the dawn of a dating apocalypse” in which users – the men in particular – used it addictively for casual sex.

I ask Rad what happened when they approached the table of girls in 2012. He laughs. “We got rejected! They were like, ‘This is awkward. We’re eating dinner. Leave us alone!’”

The brush-off did give him an idea. What if you could combine mobile phones and dating, he thought when he got home. Better still, what if there was a way of knowing whether a woman was interested in you before you made the first move? In the summer of 2012, Rad and a small group of friends got to work. Twenty-three days later, Tinder was born.

Four years on, Tinder facilitates 1.3 million dates a week. There are 9.6 million daily users, accounting for some 1.8 billion swipes a day. Tinder is part of Match Group, which includes other dating sites such as OKCupid and match.com. In November, Match Group was valued at around $3 billion ahead of flotation on the New York stock exchange – according to one recent estimate, 1 billion USD would come from Tinder.

If that were all – Rad is reported to own more than 10 per cent of the company – this would be a happy, uncomplicated tale of love, riches and megabytes. But this is start-up land. Things get complicated, quickly. And Tinder’s story (by which I really mean Rad’s story) has been more tumultuous than most.

“I feel like I have been through more in the past three years than some people do in 20,” Rad tells me with his characteristic lack of guile. He makes an unusual CEO. His forthright, unfiltered manner has polarised anyone who has watched his phenomenal rise, winning him fans – and getting him into trouble.

In 2014, his best friend and fellow Tinder co-founder Justin Mateen had a sexual harassment lawsuit brought against himself and the company by former vice-president of marketing Whitney Wolfe. Mateen – Rad’s best friend – had been in a relationship with Wolfe. When they broke up Rad and Mateen were accused of subjecting Wolfe to “a barrage of sexist, racist and otherwise inappropriate comments”.

Eventually they settled out of court for a reported 1 million USD, Mateen left the company and Wolfe enacted the sort of coup de grace that could only happen in Silicon Valley: she launched a rival dating app called Bumble – one in which it’s the female users who initiate the conversation. Neither side has admitted any wrongdoing, but the case did nothing to resolve Tinder’s reputation for having a laddish, jock-dominated working culture. (Like most start-ups, it employs a high percentage of men.)

Eventually they settled out of court for a reported 1 million USD, Mateen left the company and Wolfe enacted the sort of coup de grace that could only happen in Silicon Valley: she launched a rival dating app called Bumble – one in which it’s the female users who initiate the conversation. Neither side has admitted any wrongdoing, but the case did nothing to resolve Tinder’s reputation for having a laddish, jock-dominated working culture. (Like most start-ups, it employs a high percentage of men.)

It got worse. Shortly after, Rad was fired as CEO, with the board citing inexperience. (“It was more about mistakes not yet made than mistakes already made,” he explains, although observers were quick to note the timing, so soon after the sexual harassment case.) Critics of Rad said he was naive and out of his depth.

Six months later though, he was reinstated. Then, on the eve of Match Group’s flotation, Rad gave an interview to the London Evening Standard. He said he was “addicted” to Tinder – “Every other week I fall in love with a new girl” – and boasted about a famous supermodel who was “begging” him for sex.

This was supposed to be Rad’s second chance, but it seemed as though nothing had changed. Was he still a liability? When the journalist asked him what he found attractive he confused the word “sapiosexual” (meaning someone who gets turned on by intelligence) with “sodomy”. It went viral.

So let’s talk about sodomy, I say as he forks a mouthful of asparagus omelette.

“Oh God,” he says shaking his head. “I was really sick, so just bear that in mind.” He laughs nervously. “So grasping for the word in my head was partially because my mind was frying.” Did his mum read it?

She did, he tells me. He describes her reaction as “confused”. So did his team. “But being the laughing stock of the internet for two minutes … That taught me a lot.”

While Tinder has had a lot of growing up to do over the past three years (not least figuring out a way to monetise it), so too has Rad. He’s 30 now and although he has the boyish enthusiasm of someone ten years younger, he has the mettle of a survivor.

In interviews in the past he’s often described sitting in a bar swiping through the glamorous women on his Tinder feed as though he can’t believe his luck. Today he describes himself as “reserved” and says he finds meeting new people “challenging”. He has only had three proper relationships in his life, he tells me, and, yes, he met his last girlfriend, Alexa (daughter of tech billionaire Michael Dell) on Tinder.

“I think the perception is that I’m this LA tech party guy, but the truth is I’d rather sit in a room with my best friends than go to some crazy party.” An example: he was recently invited to the Playboy Mansion. He didn’t go.

He looks embarrassed when I ask if he is dating. “I am,” he says nervously. “But it’s early days.” All he will tell me is that she is definitely not famous, nor is she a supermodel. The far less glamorous truth is that she works in tech and was a friend before anything happened. “Actually,” he concedes, “we’re sort of serious.”

Rad is the son of Iranian-Jewish immigrants. His parents (who own a successful consumer electronics business set up by Rad’s grandfather) live in Bel Air, a smart LA suburb a short drive from Rad’s apartment in West Hollywood. Rad grew up listening to the family talk business at the dinner table. He has said, “I got a master’s degree in business before I left home.”

Interestingly, when the new CEO was brought in, Chris Payne, a veteran tech professional and business leader from eBay, he lasted less than five months before Rad was reinstated. (There was a standing ovation when he walked back in as CEO.) Why Payne didn’t last longer, no one appears to know. But when you enter Tinder HQ, the Frank Gehry-designed glass building on Sunset Boulevard, you get a sense of what might have happened (outside, Tinder tourists pose for selfies beside the logo). Tinder is a young place. There are beanbags and people hunched over laptops in high-top trainers and low-rise denim. There is a wall of candies, a basketball court, a fancy-looking drinks area that dispenses three different types of kombucha, the fermented tea, as well as wine and beer on tap (otherwise known as “the winerator” and “beererator”). You get the feeling anyone who remembers plaid shirts and Dr Martens the first time around might have a tricky time fitting in.

Last year, Tinder introduced SuperLike, which enables users to alert people that they have liked them. SuperLike is included as part of Tinder Plus, the company’s premium subscription service. The basic app is free but for a monthly fee Tinder Plus gives members unlimited swipes and five SuperLikes a day. Rates are more for the over-thirties (as Rad said, with typical bullishness, around the launch to one interviewer: “How much would you pay me to meet your future wife? Ten thousand dollars? Twenty thousand dollars?”)

The company also recently launched a new by invitation-only platform called Tinder Select, which is meant to serve only the elite users on the app, including CEOs, supermodels, and other hyper-attractive/upwardly affluent types, and Tinder Social, which essentially allows you to plan your night out by inviting people you know, as well as matching with other groups who are going out that night, too.

He could have done with that on his night out in Cecconi’s, I say.

“Right,” he agrees. “It’s come full circle.”