Is your identity as a Palestinian at the root of your drive, inspiration and self-expression?

It’s an interesting question. My inspiration has come naturally since childhood, I’m like a kid who never stops drawing. But I think there’s a drive in all of us to make pictures, it’s a human language thing – we put pictures and words together.

However, I want to state very clearly that none of my work is my self-expression. It’s not about me. It’s about creating an avenue of communication between me and those who want to communicate back, and also with society. I see being a painter as being a connection to society, where I have a responsibility not to be individualistic and narcissistic, but to look at the world outside me. Where does this idea of self-expression come from? Well, let me ask you, are the icons on a Church window a form of self-expression? Of course not – nobody ever thought of self-expression until the first half of the 19th century, with Romanticism, when Beaudelaire came up with the idea that it was all about inner feelings, and it has expanded from there. Essentially, I think the world is much more interesting outside us than inside us.

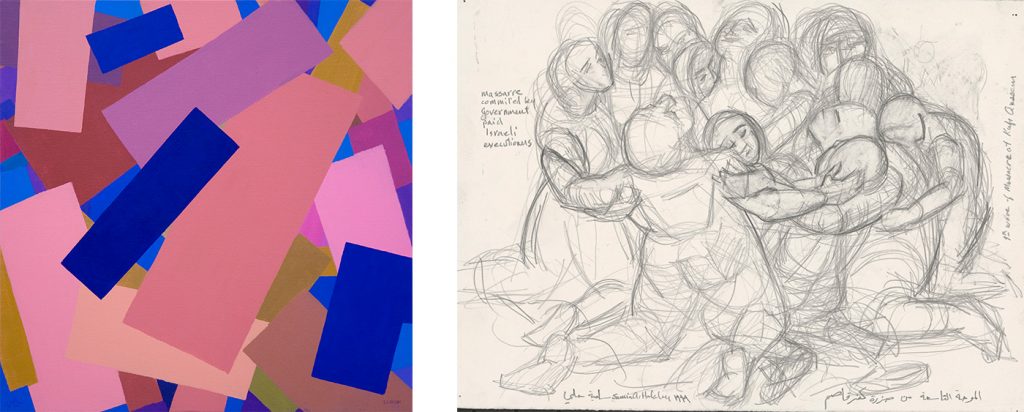

Left: The Red One, 2018 (122 x 152.5 cm) / Right: Light in Darkness, 2015 (178 cm x 178 cm)

Does the fact that you approach your art so intellectually limit you in any way?

I think there’s room for that intuitive side in my work, but it’s with a scientific attitude. As an abstract painter, I’m imitating reality, but in a different way. For example, I have ideas about cities, how they have buildings and avenues and people are moving in and out of the buildings, and when I put this all together with my experience, I can’t photograph this idea but I can intuitively come up with something that talks about that. When you see the painting, you may not see that, but you will recognise that there are some large shapes that are stable and some smaller shapes moving around them. And that might not be exactly what I saw, but it will follow the same principles. I know it sounds a little esoteric.

How did things change when you found representation with an international gallery in 2008?

What Ayyam did for me – and some people might find this strange – was to provide me with space in my studio. If I kept painting at the rate I had been before I joined Ayyam then I wouldn’t have had room for even a bed in my house. But I’m also grateful for their support. For example, last year they agreed to show a group of my paintings that were based on my book ‘Drawing the Kafr Qasem Massacre’. These paintings have some very political attributes, though I consider them to be a documentation of the history of Palestine – and the book clearly states my political ideology about the guilt Israel is exhibiting about pillaging the villages of Kafr Qasem in 1956. It’s not easy for a commercial gallery to tackle this. I’m not making art that you can interpret in any way you want. I’m making art that is definitive – and furthermore my voice is definitive.

I think the world is much more interesting outside us than inside us.

Are your abstract paintings also political?

Yes, but in a different way. I never make them about pedestrian politics, because to me that would destroy the important explorative attributes. But if you pay attention to the abstract movement of the 20th century, its basis is very political. Even while the West says the movement belongs to them, it’s actually based on the working class revolution, the capitalist revolution. It was never about abstraction – abstraction is something new and very important, but for example while Russian abstract artists were running around putting up posters during the day, they did not put pedestrian politics in their paintings; I approach it the same way.

If you look at 19th century painting before the Impressionists – the ruling class were usually the ones being depicted. But Abstraction doesn’t praise anybody. It’s not about praising rich men or women, it’s about praising principles we see in nature.

I think of a mother or father cooking a meal, and they don’t put feelings in it, they put their brains in it. They choose good ingredients and cook it so it’s healthy. That feeling of satisfaction only comes when you eat it. That’s how I think of my paintings. When people find something very beautiful, it is something in them that’s being touched. Something in them that has seen that beauty in the world already, and they recognise it in my painting. They would have no importance if no one liked them, so there’s somewhat of a social aspect here.

How long does it take you to complete a painting?

In the 1960s and 70s, when I got an idea for a painting, I would not stop till it was done, even if I stayed all day or all night. But now, it takes many many days, sometimes up to three months, because I’m sketching out ideas. And to cover an area that is two metres by four metres, that doesn’t happen overnight.

Do you find it difficult to be a Palestinian artist?

Definitely. Especially in America.

What are your thoughts on the Palestinian situation now?

Growing anger. Something has to change. Israel has to be dismantled and disarmed. They are endangering the entire globe. It’s really upsetting. And, I think the resistance in Gaza is just amazing, I can’t believe it. What they’re doing is moving the world with their lives. But I’m not depressed, I see a larger international picture with growing support for Palestine. And we’ve made many international friends, even though we haven’t been handed billions of dollars on a silver platter to bolster media support.

Left: Brick City at Night, 2015 (92 cm x 92 cm) / Right: A drawing from Halaby’s book, ‘Drawing the Kafr Qasem Massacre’ (2016), which depicts the massacre that took place on October 29th, 1956 (the same day that Israel launched a surprise attack on Egypt’s Suez Canal along with French and British forces providing an international diversion). A last minute curfew had been imposed by Israel on eight Palestinian villages, including Kafr Qasem, and the late communication to the villagers, (between 4:30pm and 4:45pm) ensured that all Palestinians returning home from work past the 5pm curfew time were slaughtered.

Your family came to the US in 1951. How have attitudes towards Arabs changed in that time?

In some ways it’s gotten worse, and some ways better. Being Palestinian is very unpopular here, especially in NYC. I remember driving here from the Midwest in 1972 to start teaching at Yale University, and I could immediately feel the difference. The Midwest was much more open, much more accepting. And I imagine California and the West Coast as well, but New York and the East Coast are very difficult. So policies keep getting worse, but we are gaining more friends.

What are your thought on the use of social media?

I’ve been using Instagram for about eight months. It’s the first time I ever joined social media and I find it fun. I’m strictly making it a doorway into my studio, not other things. I posted a red painting and asked “Too much red?” And people replied “Never too much red!” People like red.

What is your latest show about?

The key piece in the show is called ‘Simultaneous Depth’, which will be in my next show in Dubai. The word simultaneous is inspired by Futurism, which often talks about simultaneity and bringing time in as a dimension into painting. They have a non-moving painting and try to communicate the dimension of time and movement in it. So I’m inspired by those ideas, I’m trying to make shapes that are recognisable, like squares that interconnect and are seen though each other, not by transparency but through interaction.