Shaun Killa was invited by Sheikh Mohammed and his two sons – Sheikh Hamdan and Sheikh Maktoum – to attend the installation of the final piece of the museum’s façade in October 2020.

Architects don’t typically like to break out of the box when it comes to naming their firms. Take Perkins Eastman, Kohn Pedersen Fox, Foster and Partners and Zaha Hadid Architects as prime examples of this fact. But, as ever, rules are made to be broken and there are at least three noticeable industry outliers. First among them? MAD Architects, which was founded by Ma Yanson in Beijing in 2004. Then came BIG, or the Bjarke Ingels Group, which has, since 2005, been the memorable name behind some of the world’s most iconic projects. And most recently, there has emerged a world-class firm in Dubai, headed by a South African-Englishman. It’s called Killa Design and it’s producing buildings that are as cool as its name.

Killa Design’s founder and principal, Shaun Killa, moved to the Middle East in 1998 as part of Atkins’ multi-disciplinary crew on the Burj Al Arab. And, following the completion of that project, he became the firm’s design director, helping them win numerous high-profile competitions like Almas Tower, the Dubai Opera House and the Bahrain World Trade Centre (BWTC) – the first skyscraper in the world to integrate wind turbines into its design. “What I loved about Atkins was that it was a firm that was technical and design-led,” reveals Killa, who also tells us that the things he loves most about being an architect are the late nights, design work and mentoring of talent. In any case, such was the rapid rate of expansion during his time at Atkins in Dubai that the office grew from a meagre 60 people in 2000 to a 700-strong team just seven years later. Nevertheless, by 2014, and after 16 years of loyal service, Killa says he was ready for a change.

“I noticed clients were looking for something different,” he says, “a more hands-on approach where they could benefit from a closer relationship with the architect in terms of taking special projects through to completion.” So in 2015, he went ahead and took the plunge, co-founding his own practice, Killa Design, along with a former Atkins associate, Allel Hadri, who serves as their Managing Director.

Yet, this ingeniously named new studio wasn’t even up and running yet, and Killa himself was still enjoying a much-needed break, when they were invited to participate in one of Dubai’s most important recent projects. That project was the Museum of the Future (MOTF) and even though Killa had to singlehandedly compete with more than 20 international teams, he still managed to show the efficacy of a one-man-show working on a dining room table. “I submitted our proposal for the Museum of the Future, took a break, went back on holiday and then upon my return, while I was still exploring business ideas, I got invited to design another project – the Address Beach Resort for Emaar, which is a twin-77-storey tower with the highest occupied skybridge as well as the highest infinity pool in the world. I was given almost no time and was informed that a lot of huge international competitors like SOM, KPF, all the big boys, had already submitted. Honestly, not having many resources certainly made it challenging.” Still, with the few people that Shaun had, they managed to submit four options.

Around two weeks later, Killa says he received a call to go and present his Museum of the Future design to the project’s architectural jury, consisting of ministers and other high-ranking delegates. “Immediately after finishing the presentation, they just shook my hand and said congratulations you’ve won Museum of the Future, just like that.” As if things couldn’t get any better, Killa received a call not long after informing him that he had also won Emaar’s Address Beach Resort. One can only imagine what kind of mad scramble ensued, with Hadri and Killa needing to find office space while also hiring and seconding the necessary staff to get those two important projects off the ground, without any delay. “At first we had to work out of a friend of mine’s office but eventually we moved into our own premises,” says Killa about his eponymous firm which is now, as he puts it, “dedicated to creating buildings and masterplans that are sustainable, innovative, contextually inspired and have a holistic approach to the natural and economic environment”. As a matter of fact, Killa Design specialises in mixed-use, high rise, luxury hospitality, as well as cultural projects and waterfront master planning. “We now number around 80 people,” he adds.

Killa’s Museum of the Future is, to put it simply, an extraordinary piece of architecture, but the project’s brief wasn’t all that remarkable: create an exhibition space of around 12,000 sqm, plus an auditorium, restaurants, shops, parking, and of course all of the plant space to support such a museum. Yet, proving right the old adage about imagination being unleashed by constraints, it was the proposed land’s limitations in size that provided the spark for some killer (or rather Killa) creativity. “They said the museum could be on any land belonging to the Emirates Towers and that it was up to the architect where they choose to put it. So, there was an area in the front, by Sheikh Zayed Road and the Metro where there was a tiny triangular plot being used as a car park, and then there was a much larger area at the rear of the site, which represented about a third of the total site and this was empty except for some trees. As such, anyone wanting to make a traditionally horizontal museum would automatically go with the rear site. But I thought to myself that if this is such an important project for the government of Dubai, and I go and put the building at the rear, then just one or two per cent of tourists and residents are ever going to see it from a distance. You have to understand that there is so much going on in Dubai, and there’s so much to do, that the only way to attract people to anything is by advertising. And, in my opinion there is no better advertising than the actual building itself. So, I realised that this project simply had to be at the front. After all, this is a building that had been directly requested by the Prime Minister of the UAE [Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum] and that doesn’t happen very often.”

The contents of the Museum of the Future are still being kept under wraps until the museum opens some time before Expo 2020 (October 1st, 2021).

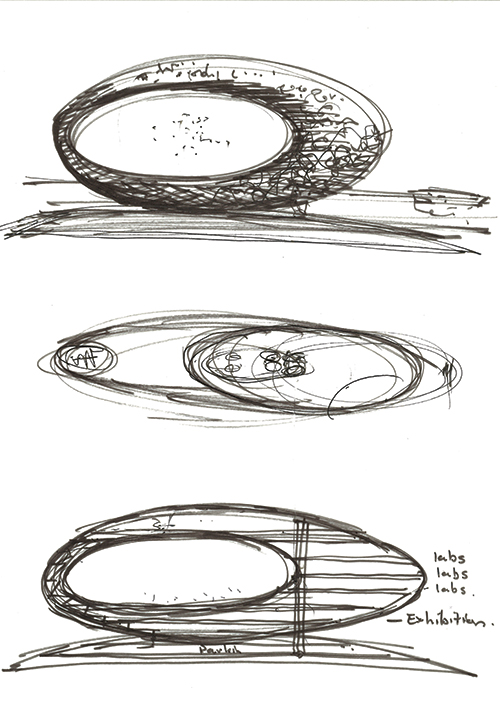

The area at the front that Killa was referring to was indeed highly visible, as it was on Sheikh Zayed Road, the main artillery expressway that every visitor to Dubai ends up taking to get in and out of the city, but it was far from a no-brainer as its tiny size severely limited the museum’s footprint and required it to be vertical in orientation. “I had six weeks to design the project and for the first three, I managed to come up with about four or five ideas that I sketched out and then had massed into 3D to have rendered. Once I got them back, I spread them out over my dining table only to realise I didn’t like a single one. They just weren’t powerful enough. They were out there and had a wow factor but they also seemed a little derivative of ideas that had already been seen before. They weren’t magnificent enough. So, I pushed all of them aside and I said to myself I can do better,” recalled Killa.

“Honestly, the biggest lesson I can teach any architect who ever works with me is to learn how to self-critique. It’s a common mistake for good architects to think that, if they’re designing something, then the work must be good. But that isn’t always the case. So, what you have to do is really challenge yourself. Can I do better? It’s a problem that starts from when you’re a fresh graduate, as you get used to doing whatever the studio master wants and so you end up relying on them to critique your work. But then, by the time you leave, you don’t have your own character or your own measure of what’s good,” continues Killa. “Anyway, going back to three weeks in, I pushed everything aside and spent the next two days beating myself up. But on the second night at around 2 o’clock in the morning I did this preliminary sketch of the museum and it’s pretty much the project you see today.” What made that design so unique was a number of key elements. First of all, Killa lifted the project above the elevated Metro line by positioning the carparks, the auditorium, the shops, the restaurants and the MEP systems in the museum’s base. Then, because he had removed the trees from the existing plot, and wanted to replace the greenery in elevation, he designed the base to be a verdant hill with everything contained within. Next, for the building itself, he decided upon an oval shape that would encompass seven floors, each measuring nine metres in height, thereby giving the museum’s forthcoming curators all the space they would need for their future of education, future of transportation, future of aviation, future of government services, future cities, future sustainability, and any other exhibition they were planning for. Then he added a void right in the middle, as a powerful representation of everything we don’t yet know about the future. “It’s the people who seek the unknown who are the ones who invent things and discover things and they are the ones who will ultimately continue to replenish the museum,” rationalises Killa. Finally, saving the best till last, he decided to contextualise the museum within the Middle East, and also Dubai, by creating cut-out windows in his design that are actually Arabic script that tells tales of the future, via quotes attributed to Sheikh Mohammad.

TOP: A rendering of Sheybarah Island, a new resort off the coast of Saudi Arabia for which Killa Design was hired to create unique overwater and inland villas. BOTTOM: The three turbines of the BWTC fulfil around 15 per cent of the office tower’s electricity needs.

I ask Killa how he came up with such a cohesive concept and he reveals that he owes a lot to the philosophies of Feng Shui. “This oval shape represents the Earth and Sky, it’s also one of the most powerful shapes of nature. In nature you don’t find any right angles: everything from a cell to an atom is built up of these kinds of structures. So, it was really a question of trying to fit the verticality of everything that was required without any columns, along with the void of the unknown, the windows containing a message and a sense of direction that suggests the museum is moving forward with the time, that’s how it all came about.”

Given the amount of fanfare the project has received concerning its LEED-Platinum environmental credentials, the highest rating a green building can achieve, I ask Killa what his reaction would be to someone like Rem Koolhaus who has previously said that “sustainability is such a political category that it’s getting more and more difficult to think about it in a serious way. Sustainability has become an ornament.”

“That is extremely sad for someone who should know better,” contends Killa, clearly ruffled by the question. “Sustainability isn’t an add-on to a building, from my point of view sustainability is a global concern and every single architect should start every single masterplan and building – from the very first line – with the aim of reducing energy consumption.”

What about his own future, I ask? What does Killa Design have in its project pipeline? It turns out they’re working on the overwater and inland villas of Sheybarah, an extraordinary hyper-luxurious resort set on a deserted island 25 kilometres off the coast of Saudi Arabia. “The project won’t require a single electricity cable or a drop of water from beyond its own shores. It’ll produce all its own energy, water and treat its own sewage using only the power of the sun.” And what might you ask ties such a grand hospitality project to the Museum of the Future? “Our aim is to always create beautiful legacy projects that inspire others to be more sustainable, more innovative and do things differently. When I created the Bahrain World Trade Centre years ago, it inspired a movement towards sustainability across the Middle East, but it also created a sense of national pride among Bahrainis. I love that and I believe the Museum of the Future is already doing that among the people of Dubai. It’s going to become a true icon not just for buildings but as something that can help change minds.”