Many of us romanticise the lives of writers, that is, until we try being a writer ourselves. It was the Slovenian philosopher and cultural theorist Slavoj Zizek who said that writing is a form of self-torture, which immediately brings to mind those incredibly frustrating moments of writer’s block or self-doubt regarding the purpose and nature of our profession.

Karim Dimechkie wouldn’t disagree, though he has made his whole life about writing, and writing well. “Every morning, I have a chat with myself for about half an hour that what I’m doing isn’t completely ridiculous,” he says to me, chuckling over a steaming cup of coffee.

Although writing is this cerebral, impassioned activity that’s inextricably linked to thought, for Dimechkie, it’s not really a conscious process. “I was a really bad writer for a while, during those years of stilted prose that came from a formal education – I thought I had to be a Salinger or a Fitzgerald – but then I came out on the other side. I became a real writer when I stopped thinking about it,” he tells me, disarmingly.

Charming in a quiet way, Dimechkie’s eyes often glaze over when he gets lost in his own thoughts. “In the same way, very little of my initial draft was conscious. It was only when I was 70 pages in, that I realised I was writing a novel. There was a certain momentum to it and it took a life of its own,” he pauses to stroke his ginger beard. “It was like dreaming onto the page,” he says, referencing his first book, which just came out this summer.

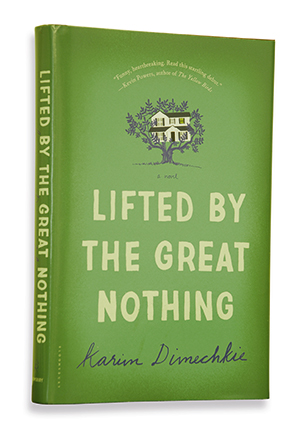

During his creative process, the characters Dimechkie created lived inside him for a while; he spent one year writing, and double that time editing the resulting 800-page manuscript into less than half its length. “I had to do a lot of slashing, killing my darlings, as Oscar Wilde would put it,” he continues. Entitled, ‘Lifted by the Great Nothing’, his novel is published by Bloomsbury and has already received rave reviews as an original and staggering debut. It even got an Oprah mention and to think that it all actually started from a joke, with the phrase “Audi, Fucks” (Howdy, Folks), which is the way Rasheed (the protagonist’s father in the novel) speaks, and was originally part of a writing prompt that Dimechkie was working on during his graduate fellowship.

During his creative process, the characters Dimechkie created lived inside him for a while; he spent one year writing, and double that time editing the resulting 800-page manuscript into less than half its length. “I had to do a lot of slashing, killing my darlings, as Oscar Wilde would put it,” he continues. Entitled, ‘Lifted by the Great Nothing’, his novel is published by Bloomsbury and has already received rave reviews as an original and staggering debut. It even got an Oprah mention and to think that it all actually started from a joke, with the phrase “Audi, Fucks” (Howdy, Folks), which is the way Rasheed (the protagonist’s father in the novel) speaks, and was originally part of a writing prompt that Dimechkie was working on during his graduate fellowship.

“At first, he was foreign, leaning towards Russian,” he explains, “but not Arab. My creative writing teacher happened to be Palestinian and she nudged me in this direction.” Although Dimechkie’s father is actually Syrian-Lebanese (his mother is French), he has only been to Beirut a handful of times and spent most of his upbringing in the US, mostly Boston and Minnesota, so the link to his roots is tenuous, at best. Yet even though it isn’t autobiographical, he has written a coming of age novel featuring a boy named Max, whose father (Rasheed) may be Palestinian-Lebanese, but desperately tries to be American in every way.

Lies are a focal motif running through the novel from the more weighty ones Rasheed (aka Reed) tells his son about their past and the nature of his mother’s death to the lighter bedtime stories he would recount at night, concerning the adventures of Kip and his ‘Man-dog’ of a brother, which were actually taken from real stories, such as Robin Hood, though Rasheed never admits it and Max doesn’t tell him he knows until much later.

“Lying is central to youth,” Dimechkie intimates. “When I started writing short stories in school – each one of which I ruined by over-working – people lied to me and I lied to myself in order to keep writing. In my mind, I was ready for the New Yorker,” he breaks into a small laugh, “Maybe it’s necessary to be a bit delusional sometimes, in order to get somewhere.”

“After studying philosophy in college, I had a dead end job in an environmental consulting firm and I decided to make my great escape to Paris, where I taught English and was also commissioned to write a blog about Parisian life.” He then applied for an MFA at the University of Texas, and got in as a Michener Fellow (the fellowship is named after a prolific American author), which officially marked the beginning of his writerly life.

During his time there, he gradually moved away from the short story as a genre. “I hadn’t perfected the form – a short story is like a watered down novel and I didn’t know how much more comfortable I would be with the huge canvas. It’s so unwielding that you can just let go.”

Without giving the novel away, a sense of what Dimechkie does with language can be gleaned from the title alone – Lifted by the Great Nothing. “There are a lot of reversals here. It’s the juxtaposition of opposites, being synthesized into something unexpected but inevitable. It’s the lifting element of grief. It’s the fact that the most alive you’ll ever be is when you are straddling life and death, which gives you wisdom and an emotional spectrum you’ve never touched before. It’s also how light and darkness can make something beautiful.”

ABOVE: The way Dimechkie writes about relationships is highly complex and unsettling, often with unexpected turns of phrase that render his writing both lucid and evocative, raw and articulate.

If we strip down that existential layer further, we move back to Max, who seems obsessed by his own mortality, and whom death seems to trick a few times; the first is at the very beginning of the novel when he almost dies from choking on chewy sweets a girl gives him at a celebration hosted by his neighbours, the Yangs, to witness the blooming of a rare Asian plant called camukra that takes 14 years to blossom, and less than five minutes to open and wilt. If this sounds like magical realism, well, it isn’t exactly that. But what Dimechkie definitely does is intertwine humour and tragedy in what he terms his ‘emotional plot’. “People have this fear of comedy but it’s incredibly profound. I have this resistance to romanticising suffering.” The result is an oeuvre that is as hilariously entertaining as it is devastatingly cruel.

The novel’s male narrator has a multi-faceted voice that’s both strong and sensitive yet where unusually, most of the traumas were somehow inflicted by the women in Max’s life, whether it was his absent mother, his father’s emotionally manipulative girlfriend/colleague or by his first lover and sexual awakening. In other words, it isn’t a story we’re used to hearing but it’s a distinctly masculine perspective. “I guess I lost patience with men who are stoic and unfeeling, this idea of the numbed man. What interests me more are these vulnerabilities.”

Dimechkie is now working on his second novel (he’s already written over 400 pages). “My first was finished a year ago,” he explains, noting how long the publishing process takes. “I remember it fondly, like you would an ex. Now, it’s like I’m with a new person and it’s all a bit surreal.” Apparently, it will be nothing like his first (girlfriend), told as a theatrical dialogue between two men. The protagonist is in a coma and his interlocutor facilitates the telling of his story, and how he ended up there.

Though we have spent the bulk of our conversation talking about the process of becoming a fiction writer, I ask him, again, how he does it, how he crafts the flow. “There’s a rhythm to writing, and I try not to lose my ear for it. It becomes an obsession, and it’s not always a happy thing but it defines the tone of my day. Funny enough, it’s the books I read as a kid, like Roald Dahl and John Steinbeck, that still inspire me and so, when I feel I’ve lost my voice, I read the staples and if something like Kafka sounds terrible to my ear, then I know that I’m just messed up in the head today.”

PHOTOGRAPHY: RIAD DIMECHKIE