Beirut was once home to hundreds of palaces. Perched on the hills of Ashrafieh, Zokak El Blatt, Clemenceau and Kantari, and spreading east to Gemmayze and Mar Mikhael, these spectacular gems of the Ottoman and French Mandate eras were built by wealthy Lebanese merchants seeking peace and quiet, with easy access to Beirut’s commercial core.

Beirut was once home to hundreds of palaces. Perched on the hills of Ashrafieh, Zokak El Blatt, Clemenceau and Kantari, and spreading east to Gemmayze and Mar Mikhael, these spectacular gems of the Ottoman and French Mandate eras were built by wealthy Lebanese merchants seeking peace and quiet, with easy access to Beirut’s commercial core.

The boom years of the 1950s and 1960s, the decade and a half of civil war, and then the reconstruction era that followed all but eradicated these incredible houses – along with the vast majority of Beirut’s historic buildings. “We have only 200 heritage buildings left in Beirut, out of 4,500 in 1994. That means that in just 20 years, we’ve lost over 95 per cent,” says Naji Raji, founder of Save Beirut Heritage, an NGO fighting for the preservation of the city’s architectural heritage.

Many of the historically significant buildings that survived the wrecking ball did so because of private initiatives, like that of Annabel Karim Kassar, who recently purchased the once magnificent Beit Tarazi in Gemmayze for a reported mega-sum of 18 million USD. “I acquired the building after five or six years of negotiation,” says Kassar. “There were 20 owners, with 20 points of view, and no one was speaking to the other.”

At the end of May, during Beirut Design Week, AKK Architects (Kassar’s firm) staged an exhibition inside the 19th century palace. Titled ‘Handle with Care’, the show aimed to engage the public in the restoration process, with survey drawings, photos and models, as well as a film presentation and round-table discussion all forming part of the experience. “I did this exhibition to help people understand their heritage and the importance of protecting old Lebanese traditions,” says Kassar.

The handsome building, which clearly should be a listed structure, dates back to 1870, and despite the wearing of time bears testament to many Ottoman architectural details. One of the most striking is a Baghdadi ceiling comprising brilliant and intricately designed tiles. “There are only three such ceilings in all of Beirut,” says Kassar. “There’s one at Lady Cochrane’s Sursock Palace, and another at the Heneine Palace in Zokak El Blatt.” Another intriguing feature is a wall fountain that possibly served as some sort of bathroom, since there were apparently none in the house.

As the name would suggest, Kassar purchased the 750-square-metre three-storey Beit Tarazi from the Tarazi family. “They lived here for a long time,” she says, adding that the house was last inhabited in 1983. She points to an old piano on the premises and explains how it used to belong to a female pianist in the household. “She was extremely eccentric,” says Kassar, “and legend had it that she would frequently throw vases at people.”

Born in France, Kassar has a long list of memorable designs to her name, both in Lebanon and abroad. Her various projects include the once popular Balima Café in Beirut’s

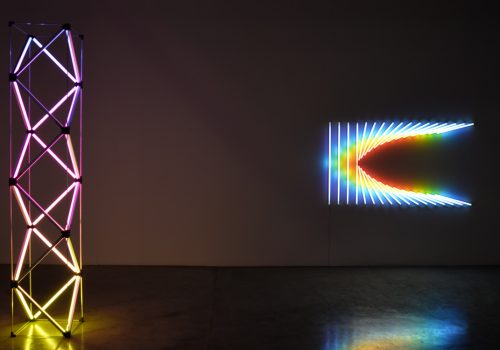

Saifi Village (now closed) and the dazzling Cinemacity at Beirut Souks (AKK served as the local coordination office for the French architecture firm Valode et Pistre, working alongside Dada & Associates who oversaw the complete interior design). In addition to Beirut and London, her firm has offices in Dubai – she designed the Almaz by Momo restaurants in both Dubai and Abu Dhabi. And most recently, in 2016, AKK won the inaugural London Design Biennale medal for its installation at Somerset House, on the banks of the River Thames.

While Kassar plans on preserving as many old architectural details as possible, she also wants her future home – now renamed Beit Kassar – to offer contemporary amenities and creature-comforts. “I will preserve colours, ceiling details and the original floors,” she says. “And I will also try to avoid concrete as much as I can because the original house had no concrete.”

The ambitious project will require a massive amount of structural work, cost millions of dollars and will take at least two years to complete. “It’s a residential project,” says Kassar. “One house. Or maybe two apartments. I haven’t designed the plan yet.”

It is located on Gouraud Street – Gemmayze’s main artery – and is walking distance to shops, restaurants, cafés and Mar Mikhael’s bustling nightlife offerings. Yet, because of its size, architectural beauty and enclosed 700-square-metre rear-situated garden, it remains a haven from the city’s frenetic life. Interestingly though,

Kassar says she has plans to re-establish the ground floor street-side area as a commercial space – she favours either a café or an exhibition space, for that is how it had been designed originally. Still, her main goal is to create a unique living experience that highlights the architectural legacy of the house. “A lot of old houses are disappearing,” she says. “We have to stop destroying them. If I hadn’t bought this house, it could have been bought by a developer who would gotten permission to destroy it.”

The architect believes that the elegant aesthetics of the Ottoman era are part of the Lebanese people’s collective unconscious. For her, it’s necessary for the Lebanese to remain connected to their roots – she believes that such a connection is essential for growth. “I very much hope that Beit Kassar will inspire others to preserve the other remaining historic buildings we have in this beautiful city.”