On September 12th, 1962, John F. Kennedy told the United States, “We choose to go to the Moon.” What JFK and the American public didn’t know yet was that by investing in its space programme, it was also getting memory foam, precision GPS, the cardiac pump, food safety standards, invisible braces and the Dustbuster. Indeed, NASA has a rich history of spin-off technology; by-products of its mission to explore the solar system and it’s definitely among the space programme’s most tangible legacies, demonstrating that ambitious ventures can reap diverse rewards to the benefit of all.

In the present day, and half a world away, Dubai is no stranger to moonshot projects. Many are stipulated by ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid himself, and space has become just another frontier, albeit one deep-rooted in history: 700 years ago, this region was in fact at the forefront of astronomy – the very reason many of the stars visible to the naked eye have Arabic or Islamic names.

The modern-day U.A.E. Space Agency, however, was formed as recently as 2014, and Dubai’s Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre was established in 2015. The centre has already successfully launched two homegrown satellites, and the Emirate is targeting Mars with plans for a probe in 2020 – the Arab world’s first mission to another planet. More ambitious still, there are plans to develop a human settlement on Mars by 2117. (In comparison, NASA’s Journey to Mars outline extends to sending humans into low Mars orbit in the “early 2030s”. Dutch private venture Mars One plans to put boots on the ground in 2032, while Elon Musk’s SpaceX is aiming to do the same in 2024.)

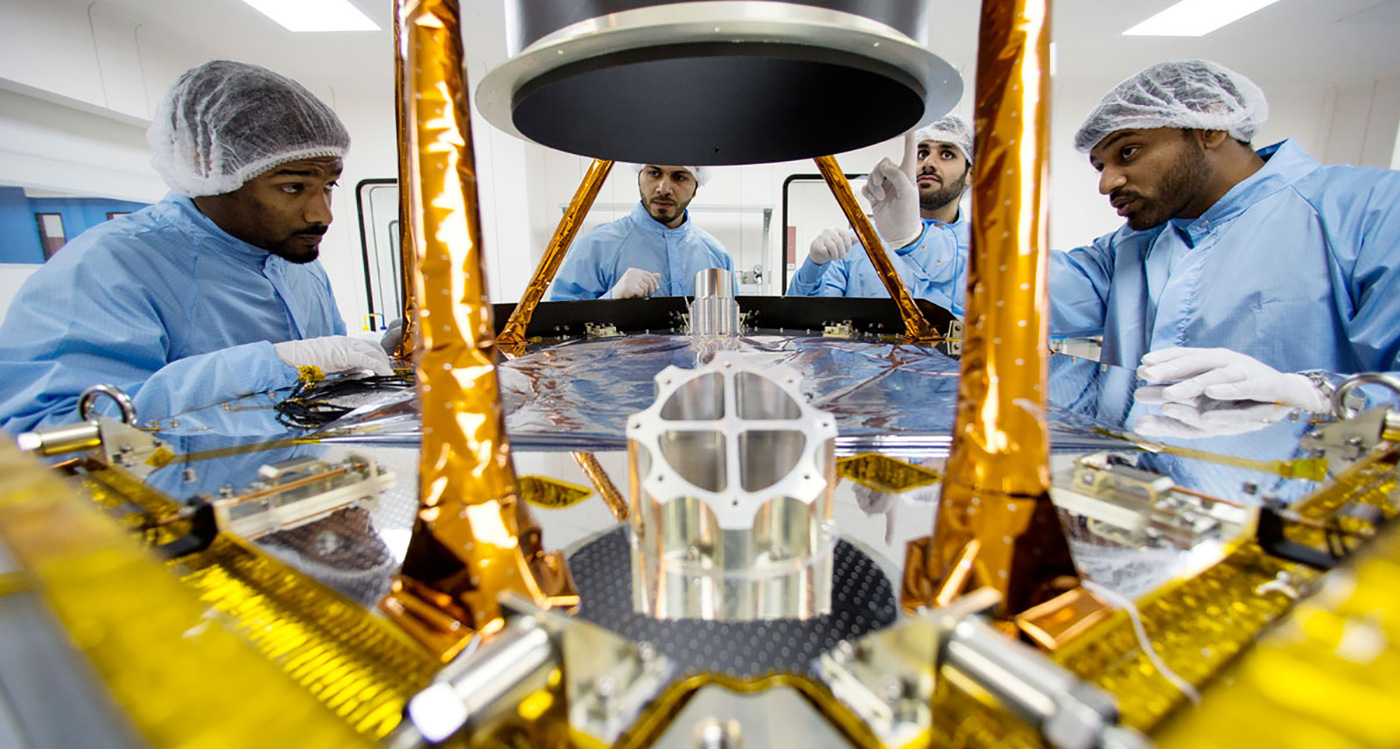

The Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) has already designed, developed, launched and currently manages two Earth-observational satellites – DubaiSat-1 and DubaiSat-2, and it’ll be putting into orbit a third, KhalifaSat, in 2018, before its Hope Probe spacecraft makes the journey to Mars in 2020.

At the World Government Summit in February 2017, the U.A.E. previewed its vision of what that colony might look like. And in September, Sheikh Mohammed and Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, unveiled renders of Mars Science City, a 136 million USD simulation centre planned for the desert outside Dubai.

Designed by maverick master builder Bjarke Ingels (BIG) and covering over 17.5 hectares – the largest project of its kind – it will include biome laboratories simulating the surface of Mars, agriculture testing areas and a museum. Much of it will be built using 3D printers, including walls made of desert sand.

No timeline was given for Mars Science City, but speaking at the launch Sheikh Mohammed told the audience, “The UAE seeks to establish international efforts to develop technologies that benefit humankind, and that establish the foundation of a better future for more generations to come.”

What the agency has on its side in this ambitious endeavour is an ideal geographical location for a launch pad, thanks to mild weather, open desert spaces and, because it is near the equator, less thrust is required to get missiles into orbit.

Still, the Emirates’ space programme – which has teamed up with over 20 space agencies around the world – is aware it’s entering towards the back of the race, and its modus operandi appears to emphasise the benefits of the journey over the final destination. It’s all part of a plan to stimulate the nation’s science industries and boost its STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) credentials.

“Our primary target is having education and outreach,” says Sarah Amiri, U.A.E. minister of state for advanced sciences, and science lead at the Emirates Mars Mission. “It’s about building people, it’s not about building buildings… It’s creating people that are creative enough to stimulate your economy and to stimulate the growth of your entire nation.” In other words, space is a means to an end.

Afshin Molavi is a senior fellow in foreign policy at John Hopkins University, and monitors trends shaping the Middle East. “We sometimes think that the only way a space programme is successful is when you have men on the moon planting a flag, or in the case of Dubai maybe rockets that land on Mars,” he says. “But a space programme is successful because of what it does on Earth.”

Whether the U.A.E.’s investment manifests itself in an off-world colony, a new generation of homegrown scientists, or the next Dustbuster, Emirati lives could be the better for it.