Speed may be life’s most powerful addiction, especially when you have nothing but wide desert road before you. Warren Singh-Bartlett spends time with the controversial Riyadh drifters who have turned an underground adrenaline-charged diversion into a growing urban sport.

When it comes to cars, I am profoundly ignorant. I couldn’t fix a flat tire, don’t know the difference between a transaxle and a transmission, can barely tell a Carrera from a Cortina and (dare I admit it), at the grand age of 38, have only driven once in my life.

Yes, once. But if there is one thing I do know about cars, it is the chest-pounding, teeth-rattling ecstasy of tearing down a deserted country road, eyes tearing, wind whistling through your hair as the trees all blur into a single streak of green.

It is precisely because I understand that kind of pleasure that I do not drive. For having flashed through the jungles of the Yucatan Peninsula, past Mayan pyramids, troupes of startled monkeys and the occasional terrified chicken in a rather saucy silver BMW convertible with reclining seats, an epic sound system and the ability to go from 0 to 60 in six seconds (okay, so I do know one or two things about cars), the idea of traffic lights, pedestrians or driving at less than 150km/h is unbearable. I mean, what is an accelerator useful for if not to accelerate?

During a recent trip to Riyadh, I discovered that I wasn’t the only person in the world unable to keep my foot off the accelerator. Coming out of the Kingdom Mall one Thursday evening, I was greeted by the sight and sound of two very fast cars – here I couldn’t be more specific than to say one was yellow and the other was blue and they both looked expensive – racing along Olaya Street at breakneck speed, weaving with suicidal insouciance in between the other cars.

Intrigued – okay, consternated – I did what any inquisitive person would do in the 21st century. I turned to the Internet. There, in the caches of various online video repositories, I found out that racing through moving traffic was suburban compared to what some young Saudis were doing.

PASSION IS FORGED INTO PRECISION, CARELESS CAREENING INTO A SINGLE-MINDED DESIRE TO DRIVE BETTER, FASTER AND MORE GRACEFULLY THAN ANYONE ELSE.

There were clips of kids getting out of moving cars and ‘surfing’ along the road on their sandals. Others were captured riding on the bonnet, crashing into crowds of spectators or sending their cars into high-speed spinouts as they drove directly into the path of a speeding truck. Such antics have turned some of the more daring – the ones who go by names like ‘Danger’ and ‘Terrorist’ – into underground heroes, whose latest stunts are advertised on the Internet and captured for posterity on DVD. Madness. Recklessness. Excess testosterone. It’s all very Hollywood in an American Graffiti kind of way.

“They compete to see who can do the most ridiculous thing,” Suleiman Alquraishi tells me, when I mention the clips I have been watching. “Most of them are driving stolen cars, some are on drugs and others are just young and a little too crazy. There have been some spectacular crashes.” Crashes, spectacular or otherwise, are exactly what Alquraishi and his friends are trying to prevent. Management consultant by day, he is a founding member of the Top Racing Team, Riyadh’s first unofficial drag-racing club.

It meets weekends in an industrial estate in Kharj on the southern outskirts of Riyadh. There, on dusty, deserted roads, Alquraishi and his friends race, secure in the knowledge that there are no other cars and certainly no pedestrians to get in the way. Come on a Thursday night and there can be anywhere from two to three hundred cars here, each eager for their moment on the strip.

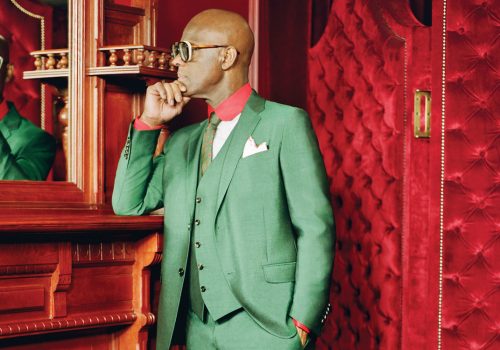

Riyadh’s youth meet every weekend to show-off their extreme driving skills and their souped-up wheels.

The crowd is mostly late 20-somethings, although there are also plenty of teenagers and the odd 40-plus. It is also fairly flush, so among the souped up Volkswagens and Hyundais there are also Carreras, Ferraris, Porsches and even a few SLRs. In fact, one of the Thursday night regulars is the branch manager at Riyadh’s Ferrari and Maserati dealership. The crowd is mixed in the sense that there are religious types with their longer beards, teenagers who have modified their own cars, bankers who have bought something readymade and several princes and this being Saudi Arabia, it’s all male, although I do hear several stories of women racing out in the desert. I am also told that at least one prominent Saudi woman competes from time to time in Formula Three events at the racetrack in Bahrain. “She’s a better driver than most men,” my confidant tells me proudly, although he won’t reveal her identity. “I might know, I might not. Her family don’t know she’s driving, much less racing, so it’s better I don’t mention her name.”

It’s clearly a big social event. Sitting on carpets rolled out beside the road, the men wait for the next race, drinking sodas and cracking jokes or else stand in small groups around the cars, checking out engines, swapping mechanical tips and generally kicking back with friends. Tech-friendly, they compare specs, exchanging information on the best way to get the most out of each car.

One group appears focussed around a lightly bearded, spectacle-wearing slightly gangling youth, who appears to be in his late 20s. Soft-spoken and unassuming, it turns out that Wajdi is something of a local hero and that, in his category, he holds the title as the second fastest driver in his age-range in the world.

The driving here, like the drivers themselves, is controlled. Passion is forged into precision, careless careening into a single-minded desire to drive better, faster and more gracefully than anyone else. Stunts like the ones evangelised online are firmly discouraged, less I suspect because the crowd here entirely disapproves, more to ensure the police have no reason to shut them down. Reckless drivers are asked to leave and if necessary, politely but forcefully driven away. Still, the grid of skid marks suggests that donuts, wheelies and the odd high-speed spin do happen.

So well organised that with the proper backdrop and real racing cars, this would be indistinguishable from an FIA meet but self-regulation does not mean sedate driving as speeds considerably in excess of 200 km/h are common. “The fastest I’ve seen here was a car that tipped out at 300km/h,” Abdallah al-Zuhair tells me. Corporate banker by day, Top Racing deputy team manager by night, Al-Zuhair’s voice warms slightly as he remembers. “We heard this loud rumble and then something flashed by. We just looked at each other, it was a real ‘what-the-f’ moment.”

For a long time, Riyadh’s racers were all dressed up with no place to go. Drag-racing was frowned upon and for a while, it was illegal to modify cars. Some of the country’s more conservative religious figures even came out against the sport claiming that at best it was a waste of money and at worse, it put lives in danger.

But eighteen months ago, drag-racing was officially recognised as a sport and since then, its status as has changed considerably. Altering a car no longer leads to being stopped at police checkpoints and having proven that it is a responsible event, the Kharj meet is no longer broken up or monitored by police. Better yet, there are three racetracks currently under construction and soon, Riyadh racers will have properly designed courses where they can push themselves even closer to the limit.

Of course once the tracks do open, the meet will have to relocate but Alquraishi sees this as a necessary and positive step towards creating a more professional racing culture in the kingdom.“There was one guy who used to come here and do some really crazy moves,” he says, as a bright blue Ferrari Spyder flashes past, “he was scary but he really knew what he was doing. A lot of the guys here have real talent; there just isn’t any way to tap it yet.”

Battling inertia, friction and the limitations of its engineering, another car flashes by, screeching and roaring, practically spitting flames. It is probably burning as much petrol in a kilometre as most cars burn in a day. I’m reminded of the admonitions of those religious conservatives. Drag-racing is wasteful. It’s self-indulgent and it’s dangerous. But it is also magnificent.

As it hurtles into the darkness, wheels barely touching the ground, car and driver seem to have overcome gravity. In this moment, they are unstoppable, so powerful and so glorious that I swear, for just a second, they seem capable not just of breaking the 300km/h record at Kharj but of breaking the bonds of Earth itself and heading straight for the stars.

Photography by Rudy Najjar