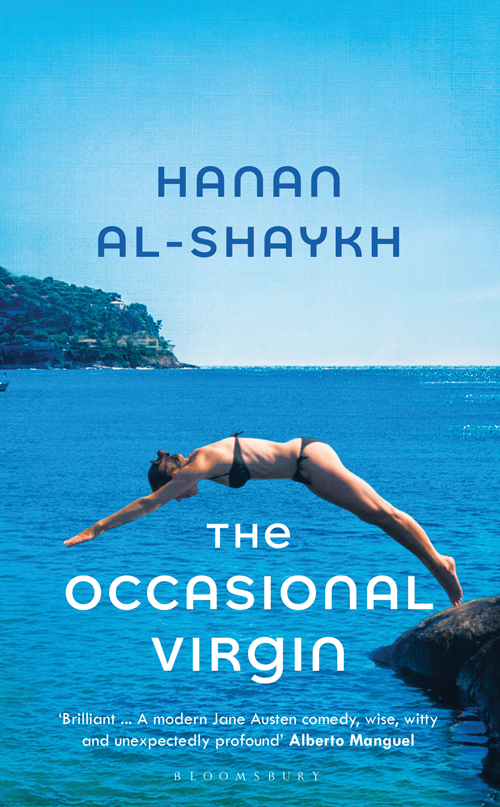

Lebanese novelist and playwright Hanan Al-Shaykh’s work often challenges traditional women’s roles in the Arab world and was initially banned in many Arab countries. Her most recent book, ‘The Occasional Virgin’ is no exception.

Lebanese novelist and playwright Hanan Al-Shaykh’s work often challenges traditional women’s roles in the Arab world and was initially banned in many Arab countries. Her most recent book, ‘The Occasional Virgin’ is no exception.

In her elegant London apartment overlooking Grosvenor Square in Mayfair, Hanan Al-Shaykh sips white tea while recounting a speaking event at the 2018 Wimbledon Book Festival in which she appeared with her daughter, illustrator and film costume designer, Juman Malouf.

“In the programme they described us as, ‘two generations of Muslim women coming together’. I almost didn’t go. For me this was not relevant, it was marketing and sensationalism, to classify us as exotic in some way. I don’t like labels and we were talking about storytelling. In the end I did it because Juman persuaded me that we shouldn’t care.”

Al-Shaykh has always had strong opinions when it comes to religion, female sexuality, otherness and independence, the predominant themes of her novels. She refused to appear at the Edinburgh Book Festival last year with a fellow invitee who was veiled – “I felt again this was an attempt to create a false conflict, to show two Muslim women with opposing views for the sake of the watchers.”

While she herself is Shi’ite – her father was a devout believer – as a young woman in Lebanon in the 1960s she remembers aspiring to be like her forerunner, fellow feminist writer Leila Baalbaki, valuing female education and the freedom even to sit in cafés alone and without religious or parental controls.

From her earliest fiction to her most recent novel, ‘The Occasional Virgin’, (which follows the lives and loves of two feisty young women – Huda, a Muslim Arab who fakes her virginity with a strawberry and Yvonne, English and non-religious), Al-Shaykh writes with great humour and humanity about what it is to be an independent Arab woman – something that has drawn criticism from more extreme quarters.

“It is not that I have an issue with Islam, I am Muslim after all,” she says, “but as a woman I have always been about being accepted for who you are and for progress and freedom across faiths. I have to be frank,” she says.

Photgraphy: Sara Lee

Her 1992 novel ‘Beirut Blues’, follows a girl who has left Beirut and another who stayed during the Lebanese civil war, depicting this tragic time that divided the nation and forced so many to flee and live far away from the country of their birth – an issue clearly still relevant today. Al-Shaykh’s ability to capture the zeitgeist in her books is perhaps what has seen her sometimes singled out.

On the refugee issue today, Al-Shaykh is circumspect: “People who make it to the West from difficult places are so courageous, I don’t think anyone realises how hard that is and what it takes. To come with no money, often no education, to try to make something, a new life is very, very brave. It should be applauded.”

That feeling, to strike out on your own and go against what society expects and indeed decrees for you, perhaps comes as much from her mother – whose life is described at length in Al-Shaykh’s 2009 memoir ‘The Locust and The Bird’. Her mother, a child bride at 14, later risked it all, walking out on Hanan and her siblings when she was just seven years old, to be with her long-term true love – something it took many years for Al-Shaykh to come to terms with.

Does she see herself as a rebel then?

“Any writer is rebellious, I think. It is our nature. Simply by writing, by what we do. But in my work – and there are others who are far more daring than I – I simply pose questions as I see them. For example, I’ve always found it perplexing when people especially in the Arab world get upset to find a young woman is no longer a virgin. Why is this a thing?” Al-Shaykh says. “We are women, creating babies is part of our make-up, love making is a natural thing, marriage or not. Ever since I was a child I asked such questions, I don’t think this is rebellious but simply natural, part of an inquisitive mind.”

“My critics say I write about sexual encounters in order to attract attention but my accounts are extremely tame compared to other writers. And why shouldn’t I write openly about that and other issues that after all, a major part of women’s lives?”

Her next project is a novel covering, in part, themes of racism, something once again topical and of which she has experience both from her own trials of being an Arab woman in the West, and of seeing the experiences of her nephew and niece whose mother is Liberian. And she is considering a personal memoir but not to cover the specifics of her life but, “the times I have lived through – from being in Saudi Arabia to being in Egypt under Nasser and of course Lebanon.”

She sips her tea and adds, “It is vital to document these periods in history for sake of the future, and through relatable and intimate stories, otherwise how can we, the world, move forward?”