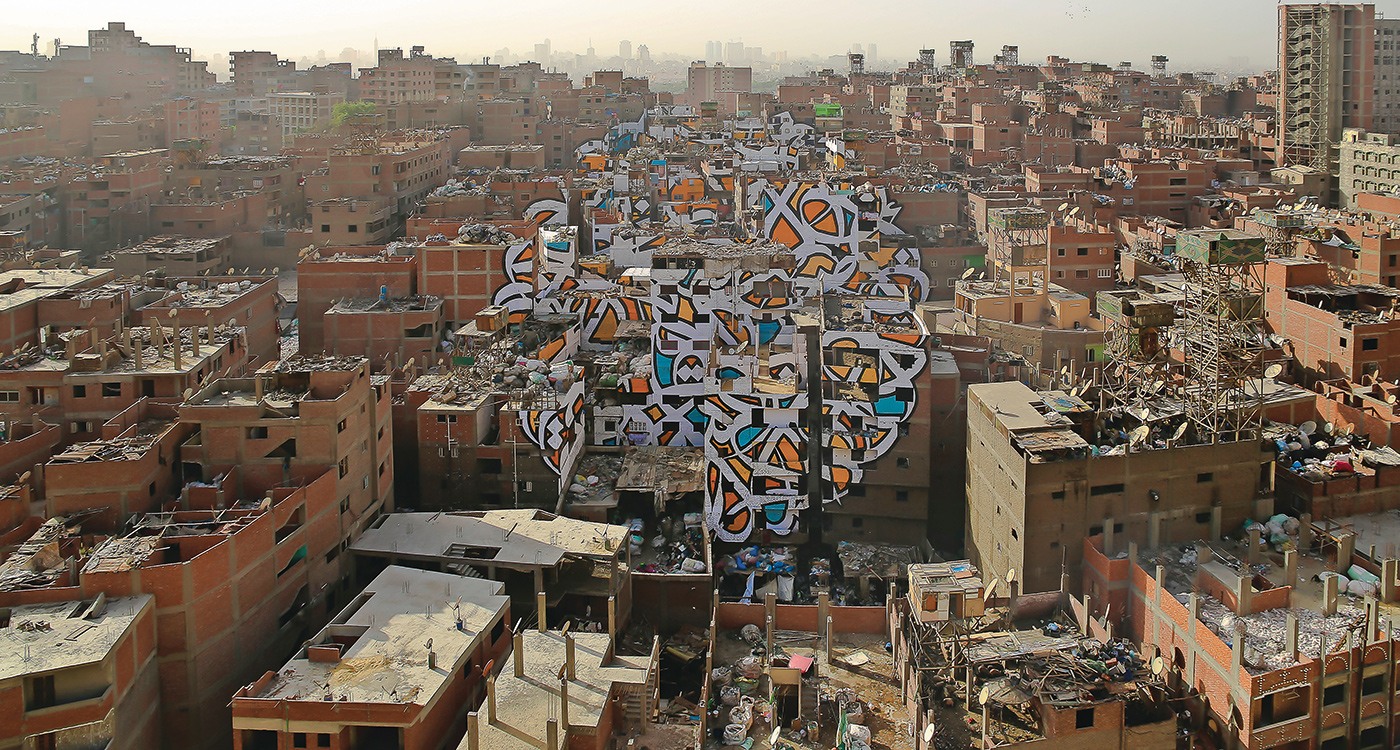

Cairo is a city of scale – it’s the first thing you’re confronted with when you see it from the aeroplane. Not only can you see the Pyramids of Giza, the city’s oldest and most famous example of art at scale, but there are also the vast tracts of red, mud-brick buildings, stretching almost to the horizon, that house the majority of the city’s 20 million residents.

Last spring, the French-Tunisian artist eL Seed added to Cairo’s landmarks when he and his team painted a huge mural spread over 50 buildings. The artwork, which depicts a circular pattern of Arabic calligraphy painted in black, white, orange and blue, can only be fully discerned from the vantage point of a mountain peak on the edge of the Zaraeeb district.

The artist’s choices, first to paint a piecemeal mural only visible in full from one location, and second to set it in such a poor neighbourhood, a Coptic Christian area where most residents are in a generations-old guild of garbage collectors, reflect his intent to engage the idea of perception.

“I knew Zaraeeb was poor but I wanted to bring beauty to it by creating an artwork,” the artist says in an interview from his base in Dubai. “To see the neighbourhood properly, as well as the artwork, you need to change the angle from which you’re looking.”

“I knew Zaraeeb was poor but I wanted to bring beauty to it by creating an artwork,” the artist says in an interview from his base in Dubai. “To see the neighbourhood properly, as well as the artwork, you need to change the angle from which you’re looking.”

eL Seed first heard of Zaraeeb in 2009, when then-president Hosni Mubarak ordered all the pigs in Egypt to be killed, in response to fear of a swine flu epidemic. The animals killed included those kept by garbage collectors in Zaraeeb, who relied on them for meat to sell, as well as to help consume the city’s organic waste.

It’s no surprise then that the residents are mistrustful of outsiders, be they Egyptian or French. “At first they were suspicious,” says eL Seed. “They were asking, ‘Who are those French guys, why are they coming here, why would they spend money on this?’”

But as time passed, attitudes changed. “One day, they would say hi. The next day they said hi and offered us tea. The following day it would be tea and a chat. The following week we were invited for lunch. And when we went home, we all cried,” eL Seed says.

Art has a way of encouraging new perspectives. eL Seed’s project, given both its physical and human scale, magnifies the potential of art to stimulate new ideas and reshape existing ones. As the work’s calligraphy reads, quoting a third century Coptic Christian bishop: “Anyone who wants to see the sunlight clearly needs to wipe his eyes first.”