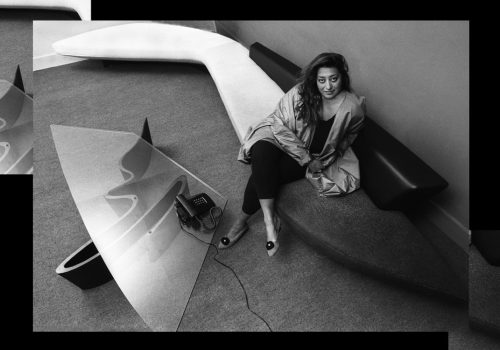

Azza Fahmy is one of the most internationally renowned jewellers to emerge from the Middle East, creating pieces that best represent Arab culture. Bespoke went to London during Fashion Week to meet with the master craftswoman.

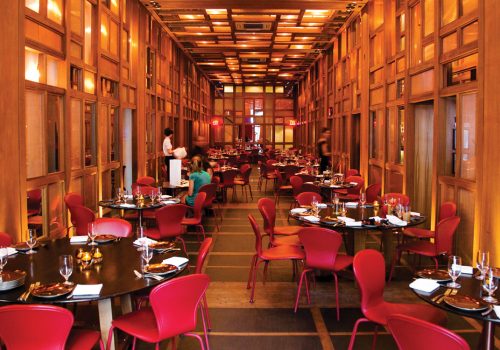

Azza Fahmy reclines in her seat looking out beyond her red framed glasses with a hint of bemusement in her eyes. For a master in the jewellery business, her demeanour is calm and somewhat understated. She’s dressed casually for our interview at the Fifth Floor Café of London’s chic department store, Harvey Nichols. “I’m more of a spiritual person,” she says in response to a question about how she came to be one of the region’s foremost female jewellery designers. (Fahmy was actually the first Egyptian female jeweller in an industry dominated by generations of men.) “I believe that it was designed for me,” she continues brushing back the dark tendrils of her bobbed hair.

MY JEWELLERY WAS TRULY DIFFERENT. IT WAS RELATED TO CULTURE AND THE RUINS AND HERITAGE. I THINK THAT’S WHY PEOPLE STARTED AND CONTINUE TO BUY FAHMY.

Fate, Fahmy believes, played more than just a cameo role in her life. Initially interested in becoming an interior designer after completing a Bachelor degree at Cairo’s Faculty of Fine Arts, she happened to be at a book fair one day, where she came across a book that changed the course of her life and the way Arab women would accessorise their ears, necks, wrists and fingers. It was a book on medieval jewellery and Fahmy was captivated. “As soon as I read the book, I knew that I would spend the rest of my life designing jewellery,” she confirms.

It’s probably a combination of this sense of sheer certitude and a vision to bring back the Arab golden age through her motifs that have made her so successful. Following her meeting with providence, she enrolled as an apprentice in Khan El Khalili bazaar where she learned the subtleties of the trade. Her training at the Khan was not without its challenges. Still no place for a young woman, she faced male detractors who would go out of their way to convince her to recede from the craft, “It was difficult at the time,” she recalls without passion or anger. “It was strange for them but in the end they accepted me and actually taught me a lot.” Following her stint at the souq, she was awarded a fellowship to study the craft at London Polytechnic’s Sir John Cass College.

It’s probably a combination of this sense of sheer certitude and a vision to bring back the Arab golden age through her motifs that have made her so successful. Following her meeting with providence, she enrolled as an apprentice in Khan El Khalili bazaar where she learned the subtleties of the trade. Her training at the Khan was not without its challenges. Still no place for a young woman, she faced male detractors who would go out of their way to convince her to recede from the craft, “It was difficult at the time,” she recalls without passion or anger. “It was strange for them but in the end they accepted me and actually taught me a lot.” Following her stint at the souq, she was awarded a fellowship to study the craft at London Polytechnic’s Sir John Cass College.

What Fahmy probably learned during her years in the Khan was how to weave Arabic calligraphy and motifs into stunning and extravagant designs. What she took from her time in London may have been an ability to revamp it and make it stylish. Being able to transport the ancient and make it wearable for the fast-paced and refined twenty-first century Arab women is no easy task. But Fahmy had an interesting playground to experiment in. For it was the 1960s and women were coming into their own. No longer relegated to being demure and unseen, they were burning their bras, joining social and political movements, wearing mini-skirts and sporting big hair. When Fahmy opened her first luxury jewellery boutique in 1969, fashion was on the brink of an overhaul and pop icons were dredging up the ancients in order to invigorate the future. These were the times of Boney M’s Rivers of Babylon. Oscar de la Renta and Nicole Farhi designs were rattling the haute-couture industry with their brash and confident colours. Fahmy’s designs thrived and continue to be some of the most sought-after pieces among style and jewellery aficionados. In short, a Fahmy piece speaks a language that transcends time, in no small measure due to its preponderance of big pieces of gold.

Close to four decades later and Fahmy’s pieces still reflect a wide range of Arab and Islamic traditions and periods. She draws inspiration from the Bedouins, Umayyads, Mamluks, Persian Safavids and Ottomans. She is also credited with having revived the use of classical poetry and Islamic wisdoms beautifully set as calligraphy and incorporated into many of her creations. These often express profound spiritual values lost to the modern Arab world, “My jewellery was truly different. It was related to culture and the ruins and heritage. I think that’s why people started and continue to buy Fahmy,” she says.

With 150 artisans under her watchful eye, Fahmy’s most recent pieces have a more modern and eclectic appeal to them. She is careful to point out that her collections – like her more recent collaboration with fashion designer Julien McDonald at this year’s London Fashion Week show – surpass trends ensuring that her creations are for the long haul and not a fetish of the moment. “The pieces are about inner beauty as well as the sensual and psychological. It’s more than just a piece of jewellery,” she says, her petite frame leaning forward. “It’s a piece of art, it’s a piece of culture and all that combined makes you feel wonderful.”