As I make my way through the busy streets of Ashrafieh, it might be due to my biased perception but my eyes are drawn to Maktabis everywhere. And all of them in the carpet business. There’s Nivine Maktabi’s Oumnia, with its modernist tribal rugs, Hadi Maktabi’s traditional Oriental carpet shop and the ultra-contemporary Iwan Maktabi, which stands out with its edgy storefront. Currently, that’s occupied by an enormous installation, a hanging bronze dome in cross-section, filled with multi-coloured spools of thread. Inside, rugs and carpets are displayed on a large scale, spread out, hung on the walls, lying on raised platforms or stacked in ways that you can catch glimpses of their different compositions and textures.

As I make my way through the busy streets of Ashrafieh, it might be due to my biased perception but my eyes are drawn to Maktabis everywhere. And all of them in the carpet business. There’s Nivine Maktabi’s Oumnia, with its modernist tribal rugs, Hadi Maktabi’s traditional Oriental carpet shop and the ultra-contemporary Iwan Maktabi, which stands out with its edgy storefront. Currently, that’s occupied by an enormous installation, a hanging bronze dome in cross-section, filled with multi-coloured spools of thread. Inside, rugs and carpets are displayed on a large scale, spread out, hung on the walls, lying on raised platforms or stacked in ways that you can catch glimpses of their different compositions and textures.

On the first floor, nothing looks especially ancient. There are so many pieces I want to touch. In the centre, some of the rugs look like there’s water running across them, like raindrops streaming and gently coalescing down a window. Look closer and you’ll see that what appears to be water – in shimmering blue, lilac and gold tones on a largely beige background – is actually Arabic script, which fades out and disappears as it runs from left to right, in streamlined fashion.

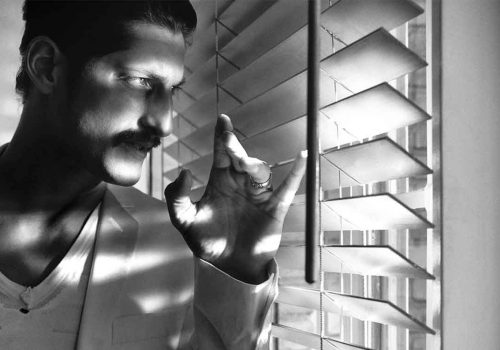

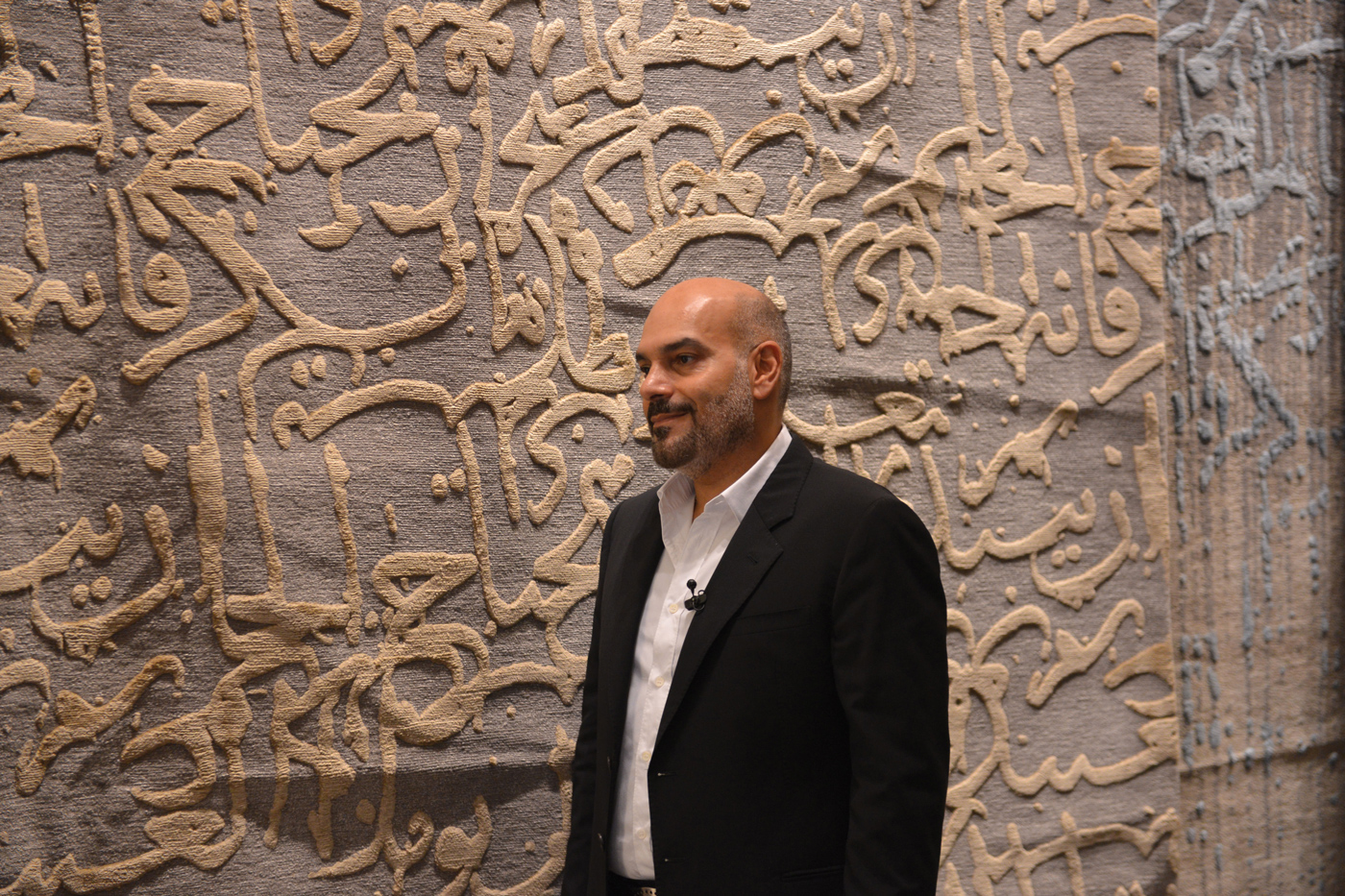

Mohamed Maktabi, who is a third-generation carpet seller turned designer from the Maktabi family, calls this pattern the ‘waterfall effect’. “You know, sometimes an art or design product looks so elaborate but the idea behind it is simple,” he tells me as we walk up another two floors of his flagship store, past the design studio and (where all kinds of older carpets – Iranian, Turkish, Tibetan and Afghan – are piled up neatly) into his office. Here, he’s hung a couple of modern art pieces on the wall by Azra Aqiqi Bakshayesh, an Iranian calligrapher, one of the few who is a woman. He explains that his eye for calligraphy comes from his first exposure to the art form by painter and sculptor, Parviz Tanavoli, during his numerous visits to Iran. “Iran has a longstanding tradition of contemporary art and Tanavoli can be considered the father of this tradition. He was also a carpet collector.” For his part, Maktabi does it the other way around as an art collector and carpet-maker.

As we chat, he gives me a brief family history – his grandfather, Hussein Maktabi emigrated to Beirut from Isfahan and his father, Abbas, became the founder of the high retail end of the business, an innovator.

“My father wasn’t very traditional in the sense that although I have five sisters, he didn’t want to exclude them from the company,” Maktabi continues. “Iwan Maktabi was an offshoot of the main business started by my grandfather and it was an instant success. So in 1995, I took a sabbatical from the mother company, Maktabi Zurich, with the support of my father of course, to work on Iwan Maktabi with my sisters and I never went back.”

Roughly half of Iwan Maktabi’s collections are contemporary, which might be one reason for its success. As Maktabi puts it, “We always have our ears close to the market and this doesn’t mean traditional rugs are out, far from that. Just that if the market is growing, it is growing in the direction of the modern and contemporary.”

While Maktabi’s sisters are still heavily involved, both in Beirut and Dubai, the main reason I’ve chosen to speak to Mohamed is because he’s designed his own couture collection, which was launched last March. It’s called Tamreen (exercise or rehearsal in Arabic) and some pieces from this collection were what had so caught my eye downstairs.

The more I speak to Maktabi, the more I understand the patient attitude he has towards journalists. A bit like a kindly academic, he is an accommodating man of few words. As a specialist himself and having collected Islamic art for years, he is probably used to having to explain where things come from and how they were made to clients. And a few people have their own ideas about customisation.

“For example, there was one client who was a calligrapher himself and he wanted the writing on the carpets in a way that you could read the names of his children inside the mesh somewhere. It was a bit challenging to realise his vision because we had to redraw the whole design. It took us 14 months but we did it,” he tells me.

As the grandson of Hussein, who immigrated from Isfahan to Beirut in 1926, and the son of Abbas, Mohamed Maktabi represents the third generation of this family business.

Now, there are only about 8 to 10 Tamreen pieces in stock and the regular production cycle for the collection is about 6 to 8 months. But there are exceptions such an octagonal piece, 11 by 8 metres for a Saudi royal, which Maktabi tells me took a whole year to produce.

Tamren is based on the Karalama, a 16th century Ottoman calligraphic exercise that master calligraphers at Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace would undertake before writing and issuing their royal edicts. “They would start by trying their hand at each letter, which connects to another and then to others, in order to transcend to the art of the word,” Maktabi explains. “The words don’t have meaning in themselves, which suits us well because it stays away from religion – religious writing cannot be underfoot. Tamreen transcends the Arabic component.”

As he says this, I understand why the bespoke piece for the calligrapher, where he wanted his children’s name legible, was an issue. And I’m reminded of Iranian contemporary artist Golnaz Fathi, whose large canvases of scrawls and blots of paint are also filled with words that don’t exist in Farsi. It’s the art of writing. The paradox is that here, you have a form of art that is so contemporary and provocative in its deconstructionist approach and yet it’s so antiquated at the same time, that it comes full circle from the past to the present, turning history on its head in a way.

The essence of Tamreen is to interweave the art of calligraphy with the art of hand-knotting in wool, silk and nettle mixes. “Our carpet-weavers were challenged to try their hands at something new due to their overuse for traditional carpets,” Maktabi adds. Iwan Maktabi manufactures in Turkey, Iran and Nepal and the Tamreen collection is all made in Nepal. A typical 3-by-2 metre carpet, in silk and nettle for instance, costs in the region of 12,000 USD.

The carpets are produced in collaboration with German carpet designer, Jan Kath, who’s quite a celebrity name in the industry worldwide. He deals with the production side of implementing Maktabi’s designs and the duo have also joined forces for Kath’s Erased Heritage collection. Both men are from family businesses with long traditions in rug design and dealership.

“His father used to buy carpets from us in Switzerland. I met Jan 10 years ago when he had stumbled into his own family business again after doing his own thing for a while. He was re-emerging as an up-and-coming carpet designer. And I liked what I saw.”

Tamreen is a customisable collection, which is highly influenced by Arabic calligraphic exercises from the Ottoman era.

I can see why. Drawing from carpets dating to the 16th until the 19th centuries, like Mamluks from Egypt and Bidjars from Iran, Kath has the Erased Heritage collection handmade by old master weavers and then distresses them so that they have a weathered, vintage look. This antique finishing process varies from a faded out look to adding disfiguring elements, such as blobs of paint, slashes or even graffiti, to them.

Apart from Kath, Iwan Maktabi has also collaborated with well-established artists from the region like Etel Adnan and Ayman Baalbaki, on carpets. I ask Maktabi how he knew that it would be good for business, so early on, to add a modern twist to carpets and reinvent the way his family business worked.

“We don’t always have this certainty. We took a risk by starting our contemporary lines but this was already 10 years ago. We’ve made our mistakes and learned,” he explains, as he takes me down to his studio to show me how the design process works. “Carpets are becoming art and design objects, the barriers between them are blurring. And as a form, carpets were always part of the Islamic art dictionary, which included wood and metalwork as well as textiles.”

In the studio, the drawing is translated by software so that the design can then produced as a 60-by-60 cm sample. “These samples enable us to see what the design will look like on a real carpets,” Maktabi continues, showing me one in particular from Tamreen. I watch the otherwise restrained man get tactile with the pieces and all of a sudden, his passion and energy shows through. “You see here, the wool and silk gives it a certain sheen, it makes it sexier. Here, I found that the gold tone was too strong and the background too dark, so we made it whiter.” I squint at the piece he is showing me, to discern all the coloured dots of thread that make up a carpet, minute in comparison to the finished product.

Maktabi notices my reaction and directs my gaze to the ground floor where, hung in its full version, looking somehow more minimalistic and more complicated than its sample. “You have to take a step back to see the bigger picture,” he says knowingly, “that’s always what we tell the weavers.” From this distance, the eroded look, with its shimmering gradations of colour and tone, is even more dramatic. In their contemporary interpretations of the old, Kath and Maktabi clearly show that what you don’t see is of just as much value as what you do.

As I go back down to where we started, I realise I still have no idea what Maktabi’s own taste is like in carpets, given his penchant for modern art. “The more you know, the more you become a purist,” he hints, with a smile. “You like the older pieces, the rarer ones. The unicorns, as I like to say.”