The history of fashion is a tapestry of lives rich in incident, of steep rises and plunging falls, glorious advances and cruel reverses. Last night, you were the toast of the town. This morning, you’re just toast.

The story of Daniel Day, better known as Dapper Dan, Harlem couturier to the early hip-hop community and associated uptown players, is as unlikely, as action-packed, as flamboyant as any whispered in the ateliers of the great houses of Paris and Milan, from which he was at first excluded, by which he was then prosecuted, and to whose leathery bosom he is now clutched.

It is a story that could have been written by Damon Runyon. A rag-trade picaresque, in which an African-American kid with holes in his shoes, fourth son of a maintenance man and a maid, who lived on his wits in the hardscrabble streets of East Harlem in the 1960s and 70s, ascended to ghetto superstar status in the 80s, having created the look of the most crucial pop subculture of the era, only to be banished from the limelight for decades.

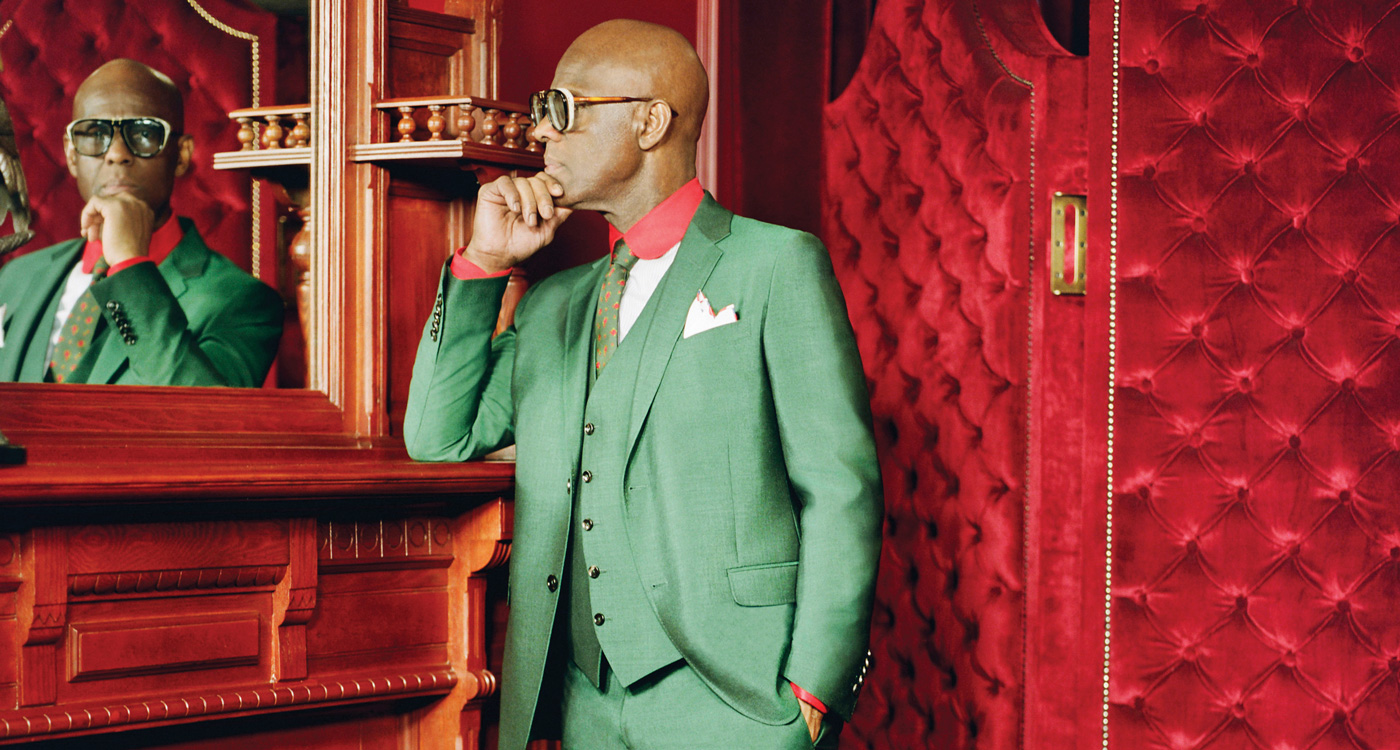

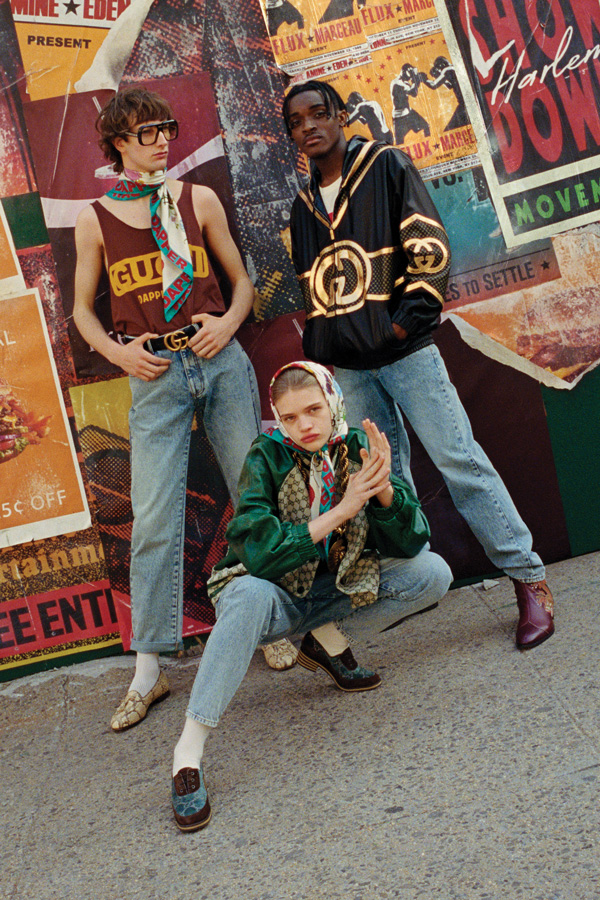

And then, just recently, to return in triumph. Now in his 70s, Day finds himself fashion’s man of the moment, the face of Gucci, a brand currently surfing waves of acclaim and success, and a collaborator with that label’s creative director, Alessandro Michele.

My appointment with Day is at an address on Harlem’s Lenox Avenue. I am deposited a block north of my destination, on the corner of 125th Street. Just a few yards from here, for a decade from 1982, stood Dapper Dan’s Boutique, where he sold garments made to order, in leather, fur and exotic skins, embossed with the monograms of Gucci, Fendi and Louis Vuitton using a silkscreen technique of his own invention.

Like the early New York DJs who sampled classic rock and soul for rappers to extemporise over, Day “borrowed” the branding of the European luxury houses and reworked it. This was long before those same houses cottoned on to the potency of street style, or even, in some cases, potential for a ready-to-wear business. In 1992, they shut him down.

Today the building on 125th Street is crowned by a billboard from which Day himself, sharp as a needle in a blue-check suit, brown ankle boots and a striped bow tie, looks down on the once benighted streets in which he made his name. The image is one of a number taken of him for Gucci’s autumn/winter 2017 men’s tailoring campaign.

The brownstone I’m heading to houses a shop, financed by Gucci, in which Day is ready to start a new bespoke service using Gucci fabrics decorated with Michele’s prints, patterns and crests. This spring, a capsule collection, co-designed by them both, will go on sale in Gucci stores worldwide.

How did a septuagenarian New Yorker once shunned by mainstream fashion, and until recently hardly known outside his own neighbourhood – except by students of hip-hop folklore – come to be in business with a luxury megabrand?

This is where this latest act of Day’s unusual career begins: with an Instagram post from sprinter and 1984 Olympic gold medallist, Diane Dixon, placing a new Gucci jacket and her Dapper Dan original side by side, above a caption: ‘Give credit to @dapperdanharlem. He did it FIRST in 1989!’

I SAID, ‘YOU ITALIANS! EITHER YOU ALL LIGHT-SKINNED AFRICAN AMERICANS OR WE ALL DARK-SKINNED ITALIANS.

And here he is now, giving interviews in the house Gucci built him. Spry, slender, in a dove-grey Gucci suit, white Gucci shirt and black Gucci shoes. An Alessandro Michele-designed outfit, but it’s had a remix: the tomato-red tie and matching socks are all his own.

“I went a little Harlem with the socks and tie,” he grins, sitting in an elegant first-floor drawing room, its walls decorated with photos of some of his most celebrated clients: hip-hop pioneers LL Cool J, Eric B and Rakim and Salt-N-Pepa. “In Harlem, if you can afford clothes that match, you got money.”

Is there a difference, I wonder, between Harlem style and Brooklyn, say, or the Bronx? “Outside of New York,” he says, “everybody wants to be like New York. Inside New York, everybody wants to be like Harlem. Harlem is the most looked up to. All the black communities in the States will tell you the same.”

The first exemplar of the Harlem style that Day can remember seeing in the flesh was a man named Bobby Titus. “He had a job on Wall Street,” he says. “I don’t know what he did. He could have been an office boy. But he dressed like the white people at the time. Bobby had a black plongé leather Burberry coat. And his walk was amazing! My brothers and me, we’d get up early just to watch him walk past and go into the subway. He was so magnificent, so powerful. It validated us.”

It was only when he left Harlem, as a young man, that he encountered other struggling communities where dress was used to communicate the desire for social betterment. Recently, in Italy on Gucci business, he marvelled at the way that country’s people are fastidious in their dress. “I said, ‘You Italians! Either you all light-skinned African Americans or we all dark-skinned Italians.’”

It was only when he left Harlem, as a young man, that he encountered other struggling communities where dress was used to communicate the desire for social betterment. Recently, in Italy on Gucci business, he marvelled at the way that country’s people are fastidious in their dress. “I said, ‘You Italians! Either you all light-skinned African Americans or we all dark-skinned Italians.’”

Day is not only elaborate in his attire. He is florid in conversation, too. He is steeped in the history of African-American culture, not just as it pertains to fashion, but to music, philosophy, religion and more. So as well as disquisitions on black style, from zoot suits to Jay-Z (and that’s just the z’s), I am treated to symposia on the legacy of slavery, British imperialism, the Conquistadors, and the history of organised crime in America. It’s fascinating and entertaining, and that’s not the half of it.

In the 1970s and 80s, drugs flooded America’s inner cities. “My best friends turned millionaires, one by one, in the drug game,” he says. “But I saw the devastation it brought.”

There was a crack house across the street from Dapper Dan’s Boutique. “I saw attractive women, young guys, professionals, go in before work. Sometimes they never came out.”

The irony is not lost on him that some of the men responsible for moving heroin and cocaine into Harlem in those years were among his customers: prominent drug barons Azie Faison and Alpo Martinez – who gave his name to a Dapper Dan parka, the ‘Alpo’ – were regular visitors to the store. Did he make a lot of money?

“You tell me,” he says. “I had 12 workers in the daytime, 11 at night. Plus five people who were family members. I had a 2,000 sq ft (185sqm) factory on the East Side. I had a three-storey building on 125th Street. I bought a brownstone, Mercedes-Benz, put my children through college. Did I make a lot of money? Probably. Was I concerned about money? Absolutely not. The only thing that mattered was to spread the message about the dark side of the culture.”

Teetotal, a non-smoker and a vegetarian for 50 years, Day has nevertheless experienced that dark side at first hand. “I got a bullet in the base of my neck,” he says. One night an attempt was made to kidnap him from his shop. When he resisted, his assailant opened fire.

What rescued him? “Divine providence,” he says. “It hit my ribs, ricocheted and landed this close to my jugular vein.” He taps his neck. “I was 13 days in hospital. I said, ‘It’s time for me to go into the underground.’”

Around that time, lawyers for Fendi began proceedings against him, alerted to his activities by an altercation outside his boutique involving another famous customer, the boxer Mike Tyson, who was photographed wearing a Fendi coat that no one at Fendi could place.

In 1992 he shuttered his shop, but he didn’t retire. “I still lived by making clothes,” he says. “I was the best-kept secret. I would travel from here to Chicago, Atlanta… All the major hustlers and rappers in the black cities knew me: ‘Yo, Dap coming to town!’”

Gucci’s suggestion they go into business together came almost exactly 25 years after the closure of Dapper Dan’s Boutique. “They said, ‘We want to give you back everything you built that was taken from you.’” As for the future, that belongs to his children and grandchildren, who will inherit the business.

In the meantime, there are orders to be taken, garments to be constructed, all bearing the logos of Gucci. Only this time authorised. He hopes that young African Americans from backgrounds similar to his own will find something inspiring in his story. He wants to act as a Bobby Titus – the Harlem boy made good – on a grander scale.

“Fashion is just a vehicle,” he says. “It’s an instrument I’m using to express something much deeper, to hopefully effect change. “That’s what this is all about,” he insists, gesturing around his splendid new shop. That, and some spectacular clothes.

Photography: Courtesy of Gucci