Chopard may not have changed their name when they switched family ownership but a lot did change when artistic director and co-president, Caroline Scheufele set up her haute jewellery collections, expanding the company’s reach from ladies’ watches to eco-jewellery.

Chopard may not have changed their name when they switched family ownership but a lot did change when artistic director and co-president, Caroline Scheufele set up her haute jewellery collections, expanding the company’s reach from ladies’ watches to eco-jewellery.

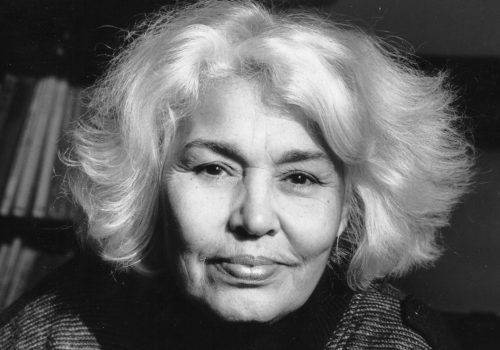

Everything about Caroline Scheufele seems to sparkle, from the tasteful jewels she wears to the animated glint in her eyes. At least that’s my first impression of Chopard’s energetic artistic director. I had briefly caught sight of her earlier this year at Baselworld, before she was about to hop on a plane to Cannes, for the film festival, where Chopard has been official jeweller since 1998.

“I’ve always loved the world of cinema,” she tells me in an interview, explaining how the partnership began. “In 1997, we opened a boutique on the Croisette during the Cannes Film Festival. On this occasion, I met Pierre Viot, President of the festival. He asked me to redesign and manufacture the Palme d’Or. Naturally, we started a collaboration and since 1998, Chopard has been producing the Palme d’Or, becoming partner to this mythical event.”

Chopard’s Palme d’Or is a handcrafted 18-carat gold frond whose leaves are sculpted as if in motion and it rests on a base shaped in the form of a small heart. This is where the symbols of love and nature, which inform much of Scheufele’s work, combine.

As I walk into the haute joaillerie section of the Chopard factory in the Swiss town of Meyrin, I’m greeted by photographs of smiling stars that line the corridor. Charlize Theron, Marion Cotillard, Kate Winslet and Penelope Cruz are all there, adorned in glittering Chopard jewels. Below each photo is the actual glass-encased Palme d’Or. Some also sport the Chopard trophy, developed in 2001, awarded to a young actor and actress of the company’s choice each year. It springs upward in the form of a curling, golden reel of film.

IN 1997, WE OPENED A BOUTIQUE ON THE CROISETTE DURING THE CANNES FILM FESTIVAL. ON THIS OCCASION, I MET PIERRE VIOT, PRESIDENT OF THE FESTIVAL. HE ASKED ME TO REDESIGN AND MANUFACTURE THE PALME D’OR. NATURALLY, WE STARTED A COLLABORATION AND SINCE 1998, CHOPARD HAS BEEN PRODUCING THE PALME D’OR, BECOMING PARTNER TO THIS MYTHICAL EVENT.

Once inside the workshop, I am shown the different designs Scheufele has dreamed up. Although she isn’t present today, her creative energy is everywhere. There’s a butterfly ring with diamonds in yellows, pinks and greens – so magnificent in size that at first, I think it’s a brooch – an emerald bracelet wrought like vintage lace and the incredible animal collection she launched in 2010 to mark Chopard’s 150th anniversary. Just imagine 150 unique animal-inspired gems, from bear cubs to lizards, in all colours and forms, some of which resemble reptiles I wouldn’t be able to name.

Then there’s Scheufele’s Red Carpet collection, a series of one-offs made especially for Cannes, that date back to 2007. “The number we make corresponds to the number of years the festival has been around, which means we produce one more unique piece every year,” she explains to me afterwards.

They’re also themed. This year’s theme is Love, both on and off-screen. “I very much wanted to pay tribute to the finest sentiments, Scheufele wrote in a press release about the collection. “The Red Carpet collection is thus adorned in shimmering colours, red accents, like the fire of passion and heart-shaped precious stones, one of my favourite cuts.”

Once again, she links her fascination for the drama of cinema, its artifice and glamour, with depictions of love and nature, most notably through floral-accented cuts and in her Poppy ring in yellow and white gold, which is made with over 700 rubies.

Scheufele says that her creations are sourced as much from her travels as they are from her daily life. “My beautiful garden has inspired me recently in many of my nature-themed pieces. I see a beautiful stone and in my mind I can already imagine how I would love to make it speak and bring it to life through a specific design.”

The artistic director doesn’t seem short of ideas. Her latest was to turn the Red Carpet Green by launching the first ecologically-friendly collection at Cannes this year. “It’s the start of a magnificent journey that seeks to promote ties between ethics and aesthetics,” she explains. “A cuff bracelet as well as a pair of hoop earrings were the two first models of this collection. We used Fair Mined gold from South America and diamonds from a Responsible Jewellery Council-certified supplier. We also announced a 3-year partnership with the Alliance for Responsible Mining, an NGO that promotes responsible mining in South America, helping them to reach certification.”

As I tour the premises, I think about the importance of knowing where jewels originate, especially in light of blood diamonds and the controversies surrounding gold mining.

Around me, a handful of artisans are tinkering, fingers blackened with wax. Two of those here are specialists in micro-setting –securing stones on mounts of tiny holes – and a man to my far left is firing at a pendant with a gun, to polish it. Inventive. I notice that every person’s workspace is personlised, covered with sketches and sometimes, family photos.

As I move behind-the-scenes in Scheufele’s world, I’m struck by the way the artistic director has managed to infiltrate every level of the factory. You see, Chopard wasn’t always known for jewellery. The family company, founded in 1860 by Swiss horologist Louis-Ulysse Chopard, was originally known for its watches. Bought by Scheufele’s father, a goldsmith, in 1963, Caroline’s passion for precious stones crept into the company’s repertoire, gradually blurring the boundary between its watches and its jewellery.

The most famous example is the Happy Sport watch. An extension of Chopard’s Happy Diamond concept, which dates back to1976, when Scheufele joined her father, it began life as a men’s watch.

“I designed it 20 years ago,” Scheufele tells me. “It was the first steel watch to have diamonds, quite revolutionary at the time. Today, we are introducing the first Happy Sport with an automatic movement to continue to propose new High Jewellery watches, one of our specialties.”

Diamonds aren’t the Happy Sport’s only ‘speciality’. I observe as a watchmaker in a white coat sits working on one, magnifier strapped to one eye. He sets each stud using tweezers and a small suction device. Once in place, the diamonds seem to float across the dial, travelling in different directions. It’s a clever trick. The diamonds are actually inserted above the dial between two transparent crystal layers. They never actually touch the mechanism, only move above it.

Elsewhere, the watchmakers are orchestrating watch movements. The kits and components come from the village of Fleurier, Chopard’s second production site, where its innovative L.U.C complications and other in-house movements, are produced.

I enter the men’s watches section, domain of Karl-Friedrich, Caroline’s brother and co-president of Chopard. Here, the work of stamping, setting, assemblage and finishing is dominated by larger than life, noisy machines. Through a viewfinder, I watch the most curious-looking one dribble oil over the revolving watch components, to lubricate them before putting them together in a pre-programmed pattern. Once the machines have done their work, the finishing touches are done by hand in a quieter area.

And then, I’m taken below ground. Here, in a brightly-lit space – there are windows running along the upper level which reveal the greenery outside – Chopard runs its own gold foundry. It produces 14 tonnes a year. My guide explains that the gold is baked in the oven like a cake, with different recipes for different alloys. The ore is heated to around 1,000 degrees to melt it, remove impurities and combine it with other metals, such as copper. Then it is solidified in water, hammered and thinned into blocks of rose, white or yellow gold in enormous machines that work a little like pressure cookers.

I can’t help but be impressed. My tour, however, is at an end. I’m left to linger for a while in Chopard’s private museum, also housed in the same building. It’s a treasure trove of 18th century pocket watches, ancient worktables, leather-bound books and archived press materials. It seems a fitting place to finish, detailing the history of a company and the machinery behind it.