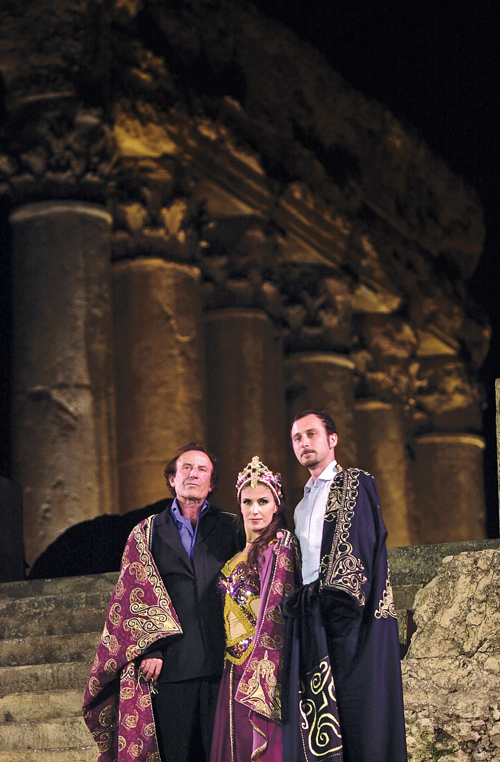

ABOVE: Abdel-Halim Caracalla stands with his children Alissar and Ivan, who just played a role in their 2001 Ballbeck production of Two Thousand and One Nights.

The Caracalla Dance Theatre is the leader of its kind in the Middle East. Established over 45 years ago by Abdel-Halim Caracalla, it is now run by his children Ivan and Alissar who maintain its cultural message of transforming Arab heritage through the international world of dance.

Step into the Caracalla premises and you’ll enter a world of grand columns and ornate frescoes. Its cafeteria is all velveteen corner diwans. There’s a baroque feel, simultaneously ancient and Oriental. Everyone here walks with a dancer’s gait, from the woman behind the coffee counter to what I take to be Eastern European students – Lebanese it may be, this troupe is international. There’s the hush of seriousness and the rush of activity.

This is Caracalla’s world, as originally envisioned by the founder, Abdel-Halim Caracalla in 1968. It serves as both the stage for the company’s productions and as a school. A student of the modern dance pioneer, Martha Graham, Caracalla’s fame both at home and abroad – there have been performances at Sadler’s Well, the John F. Kennedy Center for Performing Arts, Carnegie Hall, the Théatre des Champs-Elysées – has made Abdel Halim a cultural ambassador of sorts for the Arab world, a man who’s taken traditional dance to an entirely new level. In fact, I could swear that he was sitting and having a coffee as I walk past, distinctive in a beret and moustache.

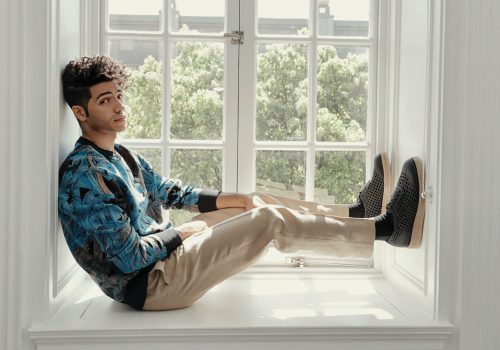

I’m here to see Abdel Halim’s son, Ivan, who I soon find out played an integral role in transforming the theatre, when the family business moved from being a small studio to the regional musical theatre giant it has become today. “When I tell people it’s like Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, they laugh at me,” Ivan says in his characteristically disarming way, an essay in elegance in a white collared button-down shirt, black-rimmed glasses and well-groomed Van Dyke. “I’m not comparing it to the Sistine Chapel, what I mean is that the artisans were using the same techniques for the frescoes. It was incredible to watch.” Ivan had the craftsmen brought over from Milan. “We were seeking to give this building an identity and since applying Western techniques to Oriental subjects is pretty much what Caracalla does, it was a fitting choice.”

The troupe may have finally garnered well-deserved respect but getting to where they are has required years of hard work and dedication. Ivan and I discuss the irony of his father having to go against his parents’ wishes in order to study dance in London and Paris, while he and his sister, Alissar are faced with a whole new challenge, that of taking their father’s legacy further in their roles as director and choreographer respectively.

“My father didn’t compel us to be part of Caracalla but he didn’t want to put everything he had invested in, mind, soul and body, in the hands of people he couldn’t trust completely. He encouraged us but he was also very strict about it. Though he never raised a finger, there was this constant mental challenge. We had to prove ourselves to earn our right to be on stage,” Ivan continues. “1994 was my directorial and dancing debut, for our adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew, It was the first time I didn’t just stand there holding a flag on stage, which I had done many times before. I’ve learned that when you’re on stage, you better have something to offer, otherwise, you shouldn’t be there. This is the kind of profession that can destroy you.”

IT’S AN INCREDIBLE RESPONSIBILITY TO INHERIT THE KINGDOM MY FATHER BUILT FROM NOTHING, AND TO DEVELOP IT AND DETERMINE ITS CONTINUITY. I DON’T SEE IT AS JUST A FAMILY BUSINESS, IT’S MORE OF A SOURCE OF IDENTITY IN THE ARAB WORLD.

The respect and even awe Ivan displays towards dance and theatre has been with him since he was a boy, when he would sit in his parents’ home near Beirut’s National Museum and watch rehearsals. I ask him if it is true that in those days, they danced in the living room. Saying that they did, he adds that while it was his playroom too, he had to be quiet when they were practicing.

This was before Caracalla opened its first studio, which was destroyed seven times during the civil war. “Every time it was hit, we would go back to sweep up the broken glass and debris. It was heart-breaking,” Ivan remembers. “Then the dancers would rehearse and we would carry on.” In fact, almost half of the productions Caracalla has staged were created during the war. The show, as they say, must go on.

“The opposing factions didn’t agree on much, but they could agree on Caracalla and its cultural identity,” he says, describing how the army would escort the troupe across the lines that divided West from East, the Shouf, Tripoli and Sidon, dropping them off at crossing points, where they would be escorted by another armed division, military or militia, to the actual performance itself. Even in war, the need for culture doesn’t disappear entirely.

As we speak, I gain an ever clearer sense of what kind of man Abdel-Halim is. Resilient, with a strong sense of discipline, he also clearly values the virtues of leadership and lives by the motto practise makes perfect. It turns out Ivan is actually named after his father’s Greek coach from the days when he was a pole-vaulting champion. “Ivan enabled my father greatly, and he was always looking for a higher bar to cross. His whole career began with sports,” he explains, adding that he approaches his troupe as if they were an army division, training them 8 hours a day, 6 days a week – the kind of gruelling schedule that’s a regular feature of any serious dance company. What’s admirable is how Caracalla Senior didn’t let instability and uncertainty get in the way of putting on spectacular performances. Even years after the war, when the Israelis again attacked Lebanon in 2006, his training habits encouraged his dancers to come in for an hour or two of rehearsal, whenever he thought it was safe for them to move around.

The dancers, regardless of where they came from, proved staunchly loyal. They persevered and stayed with Abdel-Halim during the war. “They trusted him,” Ivan tells me. “If you look at the most prominent generals and leaders in history, they were the ones with loyal followers. They were successful not just because of their tactics. Take Alexander the Great or in dance, Maurice Béjart, one of the most important choreographers of the 20th century, his dancers believed in him and his vision. My father created this extended artistic family of dancers. And we really take care of them, it’s not just that they come to the theatre to practice, and then leave. Some of them we find through auditions in Kiev and London, they are foreigners here, so we find them places to stay, they are like family.”

“It’s true we work as a team but we don’t pat each other on the back,” he continues, returning to the topic of his family. “We clash but see these conflicts as opportunities from which a better idea will spring. We push ourselves, we aren’t satisfied with the first idea. Mum, who used to be a dancer, is the thread who holds us together. Dad also needs to present as he’s the genius behind it all.”

Talking to Ivan in his office, he comes alive as a dramatist when he speaks of the intellectual and cultural references behind his productions, the history and compositions they sample. “My relationship to each show is like a love affair where you are bound to be disappointed afterwards. For several reasons, you need to disengage when it’s over. If you remain enamoured, you get attached. You need to learn how to walk away without looking back, how to desert it so you can take on the next production,” he says, flashing a smile. “It isn’t a very monogamous life I’m afraid.”

He mentions the troupe’s highlights: their international debut in Japan’s Osaka theatre in 1972, the commission by Sheikha Mozah for the launching of the Qatar Foundation, the Sheikh Zayed show supported by the Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage and patronage from Jordan’s King Hussein but what stands out most in his head is his encounter with Franco Zeffirelli.

“My Dad called me up one day and said, ‘guess who I am having dinner with? Zeffirelli.’ I told him he shouldn’t joke about such things,” Ivan explains. But he wasn’t. “Zeffirelli was thinking of doing something in Lebanon. I drove him from Beirut to Baalbeck the next day. Those 90 minutes alone were the beginning of a new life for me and I will be ever thankful to this man.” Ivan left for Italy to work with Zeffirelli on his film and opera productions for the next five years, from 1997 to 2002. “We went from the Metropolitan Opera in New York to the Tokyo Opera House, from Convent Garden to the opera houses in Rome and Napoli. It changed my life and my experiences allowed me to bring the company to a whole new level when I came back.”

He’s referring to Caracalla’s evolution from concentrating on the choreography to also emphasising the overarching narrative, through scenography, sound design, décor and lighting. “It’s much more theatrical now. Not all those on stage are dancers, some are actors and singers. And on the educational side, the school has 1,500 students. Alissar holds the reins there and she’s made it international,” he pauses and then laughs ruefully, “I think there’s a reason why we don’t have children.”

MY FATHER DIDN’T COMPEL US TO BE PART OF CARACALLA… HE ENCOURAGED US BUT HE WAS ALSO VERY STRICT ABOUT IT… WE HAD TO PROVE OURSELVES TO EARN OUR RIGHT TO BE ON STAGE

The troupe now has a solid core of 65 dancers, which can grow to over 100 for the larger, touring productions. Their latest show, Kan Ya Ma Kan, which premiered in Beiteddine in 2012, marks the first production Abdel-Halim hands over to his children, since he was on an official visit to Algeria.

“My Dad called me the day after opening night and he just cried,” Ivan tells me emotionally. “It’s his reason for living you know but I think he felt he did the right thing with his son and daughter.”

Kan Ya Ma Kan shines in a sea of elaborate costumes, sparkling crowns and the flowing headdresses as energetic dancers sway to the rhythms of bells and drumrolls, to the music of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Shehrazade and Ravel’s Bolero. “I like to think that Rimsky was enamoured with a woman from the East. This sense is present in every note and undulation of the violin. Ravel was able to use one tune that’s repeated over 14 and a half minutes, to create his incredible composition,” Ivan explains, making grand, conductor-like gestures, his passion bursting forth.

Ivan also created the dramatic film-like backdrop of landscapes and ancient cities. At the end, the dancers break into a dabkeh routine, raising the hybrid dance of fluid balletic movements and the theatrical drama of modern dance to a crescendo of energetic, earthy brisk folk dance. An older man was particularly popular with the audience. This was Omar, Abdel-Halim’s brother, who I had mistaken for Abdel-Halim earlier. The two grew up in Baalbeck, which is where they also first witnessed the magic of classical ballet at the annual festival, forever changing Abdel-Halim.

“We never forget where we’re from,” Ivan surmises. “There’s something magical about Baalbeck. There’s a reason why the Phoenicians built their altars and the Romans their temples there. I can identify with the way men and women put hand to hand and shoulder to shoulder in the dabkeh. This identity is like a seed that’s planted and takes hold of you, flourishing suddenly.”

What weighs most heavily on Ivan’s head at the moment is creating the right conditions for the seed they planted to continue to grow. The great struggle Caracalla has always faced is survival, initially because of war and later for having to be self-sufficient – Caracalla is neither subsidised nor supported by the Lebanese government. It means that sometimes, they need to rely on commissions to keep going and finding a way to make the company viable and sustainable is still one of Ivan’s greater challenges.

Another is being the son, under the mentorship of his father. “It’s a double-edged sword and carries with it a curse and a blessing. Is it a gift or a burden? I think time will answer this, through the trials and achievements, successes and failures. It’s an incredible responsibility to inherit the kingdom my father built from nothing, and to develop it and determine its continuity. I don’t see it as just a family business, it’s more of a source of identity in the Arab world.”

Ivan is poetically contemplative when he describes how he sees his father today. “He’s someone who illuminates the path to best travel. Perhaps from the fatherly point of view, the father is becoming the son and the son the father in the circular journey of life, but from the artistic perspective, our journey isn’t circular at all, for creation is an ongoing process of enlightenment. This is the current route of Caracalla the father, a journey of continuous search, rising up into the infinite.” And with that, I can see that son, like father, is reaching for the higher bar to overcome.