Nestled between two gigantic neighbours – China and India – the tiny Himalayan nation of Bhutan is a majestic, serene and beautiful country that’s admired not for its gross domestic product but for its gross national happiness index. Emerging from the pint-sized terminal at Paro, Bhutan’s sole international airport, new arrivals are greeted by dazzling sun, crisp mountain air and most invitingly, a bevy of genuine smiles. The warm welcome from assembled guides dressed, as many Bhutanese still do, in pristine national costume, brings colour back to the faces of air travellers who have just experienced one of the most nail-biting landings on the planet; only 12 pilots in the world are certified to land in Bhutan, as it requires a difficult manoeuvre that involves turning sharp left to avoid the mountain and landing in the valley as brightly-painted houses whip past on either side.

LEFT: A suite at Bumthang, Amankora’s newest outpost. RIGHT The 24 suites at Amankora’s Paro lodge come with stunning bathrooms. Hidden by a thick pine forest, Paro is Aman’s closest property to Bhutan’s international airport (plus the largest and most impressive of their properties in the country), it usually serves as the start and end point for travellers jumping between Amankora’s five lodges

It’s my first visit to Bhutan, although the remote Himalayan Buddhist kingdom has been on my personal bucket list for a decade. I’ve always been intrigued by a destination that has remained so well fortified against the onslaught of modernity, retained an ancient (and well loved) monarchy and which measures its progress not in dollar signs or market points, but by happiness, literally.

Momos, a type of dumpling native to Bhutan.

Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (GNH) index, a measurement of the collective contentment of the Kingdom’s 740,000 citizens, is a remarkably progressive approach for a country named after a thunder dragon. Coined in 1972 by Bhutan’s fourth king, HM Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the idea has evolved into a socioeconomic development model recognised by the UN. There’s no doubt Bhutan is a land of happiness and peace, and that translates to an increasing number of well-heeled visitors who cling to their airplane armrests in pursuit of their own little slice of Himalayan harmony.

Then again, not just anyone can come and see this “last Shangri-La”. The former king was prescient in wanting to deter the backpacker set and tap into high-value, low-volume tourism. As a result the visa application process is quite stringent and surprisingly cumbersome, with conditions like a requirement that all visitors book their trip with a licensed Bhutanese tour operator and have local guides at all times, plus there’s a minimum per diem of 200 to 250 USD per person, depending on the season.

Though the Aman Resorts’ Amankora was the first five-star luxury hotel to open in Bhutan in 2004 (it has since expanded to include five distinct lodges – Paro, Thimpu, Gangtey, Punakha and Bumthang – dotted around the country, all of which are amazing), my own trip began at the Como Uma Paro, an intimate 29-room retreat that, like virtually everything in this vertiginous nation, is perched on the side of a steep hill. Here, it’s very easy to be happy; there are roaring fires, comfy beds and shy but attentive staff dressed in elegant, silken kira dresses. There’s the Como Shambala Retreat, home to Bhutanese-inspired massages and an indoor pool, and Bukhari, a restaurant serving healthy hand-ground buckwheat noodles, yak dumplings, and Como’s iconic juice blends.

The next morning I’m off to Bhutan’s capital, Thimpu, a serene little city nestled on the west bank of the Thimphu Chuu, making it the world’s third highest capital. Nearby a police officer, resplendent in his uniform and white gloves, directs traffic from a tiny hut decorated in bold reds and yellows. Bhutan has worked hard to improve its infrastructure, but when the country’s first traffic light was hoisted at the same intersection, so many accidents occurred that it was quietly lowered again that very evening. I guess happiness is sometimes in not fixing something that isn’t broken.

The quiet of the capital is only interrupted by the cries from the khuru field, where the national sport of archery is the biggest ticket in town most weekends. Players adorned in national dress aim for a tiny bullseye from some 150 metres downfield. Teams jostle and challenge each other across the length of the field in an artful tradition called kha shed, which involves verbal teasing adorned in rich literary language that’s meant to distract the competing archer. When the arrow is finally loosened, all eyes turn to the sky, the bolt streaking through the sunshine and landing steps from leaping opponents. A missed shot is met with more polite taunts, but a successful strike leads to a respectful, traditional dance that blesses the target and acknowledges the talents of the archer. There are smiles, singing and dancing at both ends of the field before skills are praised, arrows bestowed and friendly rivalries stoked with more than a few drops of local ara rice wine.

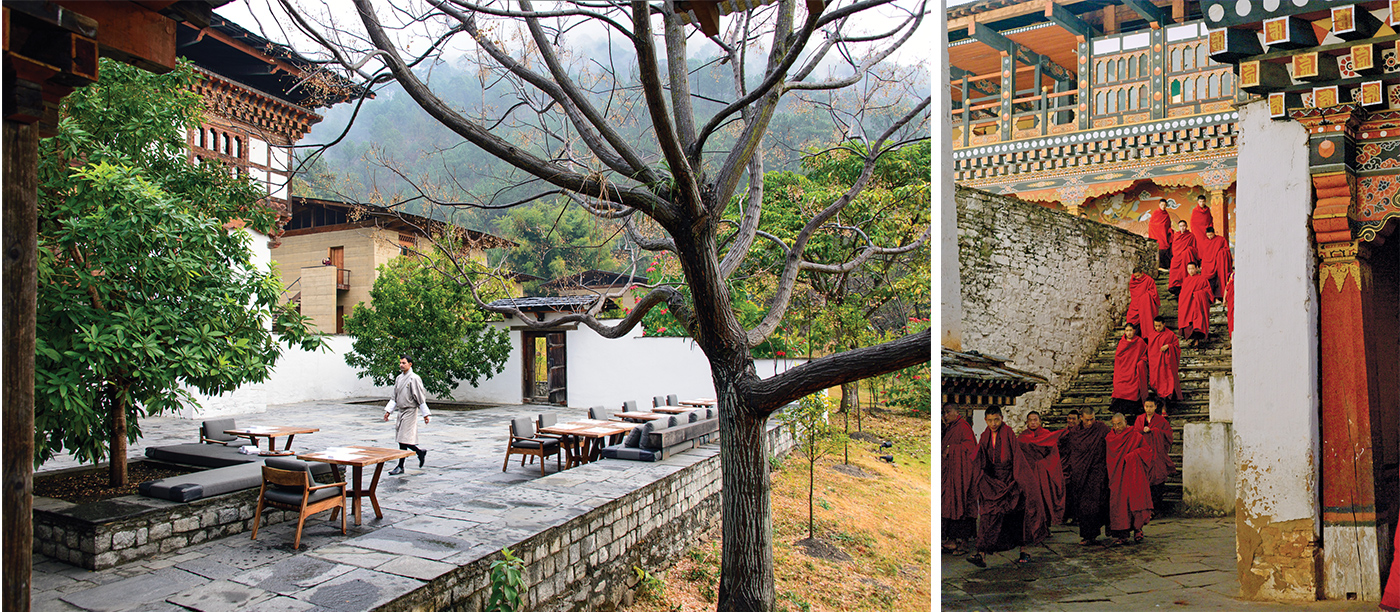

LEFT: A shot of the eight-suite Punakha Lodge. RIGHT: Monks in Paro’s Rinpung Dzong monastery.

Atop the Dochula Pass I visit the solemn Druk Wangyal Chortens, a memorial of 108 stupas, spherical structures, notably dedicated to both soldiers and rebels who fell during the Assamese uprising of 2003-04, the first military conflict ever for the Royal Bhutan Army. It is telling of Bhutan’s respect for life and peace.

We soon head down the dusty road from Como Uma Punakha to a field beside the river where a modern helicopter awaits. In a pioneering partnership with the Royal Bhutan Helicopter Service (the kingdom’s fledging air ambulance fleet) well-heeled travellers staying at Como’s properties can now be among the first to visit some of the kingdom’s most remote corners as part of a six-night scenic heli-adventure that includes two flights – from Paro to Punakha via the rarely-visited Laya Valley, and from Punakha to Paro via the Utsho Tsho, the Turquoise Lakes of the Labatama Valley – but I’ve managed to hitch a ride in the opposite direction, visiting Laya en route to Paro’s international airport.

With a roar from the turbines that reverberates off the mountain sides, British captain Nik Suddards pilots the new Airbus helicopter up Punakha Valley, offering a bird’s eye view of the Nalanda Monastery and the sacred peaks of Jigme Dorji National Park, home to snow and clouded leopards, Himalayan black bear, red pandas, and ancient glaciers. After 40 minutes in the air we circle the tiny village of Laya, the Kingdom’s highest settlement at 4,115 metres above sea level.

Located in one of the most remote and least developed parts of the country, Laya is home to the semi-nomadic Layap people, a relatively affluent community that harvests cordyceps, a rare fungus used in Chinese and Tibetan traditional medicine. Their Bey-yul, or hidden paradise, is protected from mischievous spirits by an ancient gate at the village entrance. Foreigners are extremely rare in Laya, as are helicopters, and after landing above the village, we’re greeted by curious locals including two young sisters – I am the first foreigner they’ve ever seen.

Our last day is spent climbing to the Taktsang Palphug Monastery, a prominent Himalayan Buddhist site also known as Tiger’s Nest, set on the side of a dramatic cliffside, Reaching the top is not as challenging as it was it was built in 1692, when visitors had to risk life and limb on tiny footholds set into the rock to reach the top, but it is still a minor feat with 700 steps down into the canyon and back up again to the monastery (which need to be repeated on the hike home). Thankfully, once you make it to the shrine and take in the soaring views across the Kingdom’s mountainous interior, you’re guaranteed your biggest Bhutanese smile yet.