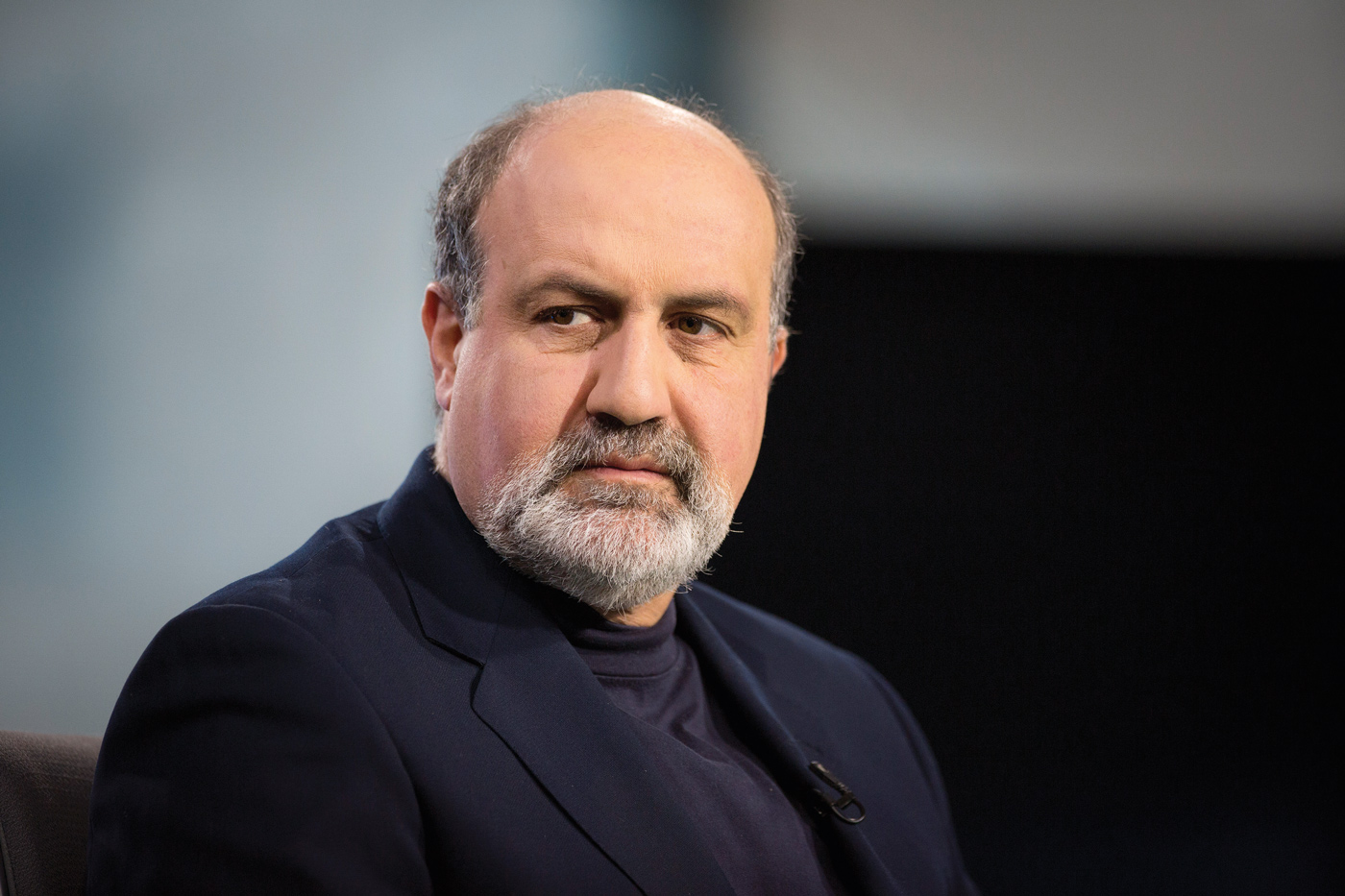

Nassim Taleb, the controversial thinker who predicted the 2008 financial crisis hates bankers, academics and journalists. He also eats like a caveman and goes to bed each day at 8pm. Intrigued, we took the risk of meeting him.

How much does Nassim Taleb dislike journalists? Let me count the ways. “An erudite is someone who displays less than he knows; a journalist or consultant the opposite.” “This business of journalism is about pure entertainment, not the search for the truth.” “Most so-called writers keep writing and writing with the hope, some day, to find something to say.” He disliked them before, but after he predicted the financial crash in his 2007 book, ‘The Black Swan’, a book that became a global bestseller, his antipathy reached new heights. He has dozens and dozens of quotes on the subject and if that’s too obtuse for us non-erudites, his online home page puts it even plainer: “I beg journalists and members of the media to leave me alone.”

He’s not wildly keen on appointments either. In his new book, ‘Antifragile’, he writes that he never makes them because a date in the calendar “makes me feel like a prisoner”.

So imagine, if you will, how keenly he must be looking forward to the prospect of a pre-arranged appointment to meet me, a journalist. I approach our lunch meeting at the Polytechnic Institute of New York University, where he’s the ‘Distinguished Professor of Risk Engineering’, as one might approach a sleeping bear: gingerly. And with a certain degree of fear. And yet there he is, striding into the faculty lobby in a jacket and Steve Jobs turtleneck (“I want you to write down that I started wearing them before he did. I want that to be known”), smiling and effusive.

First, though, he has to have his photo taken. He claims it’s the first time he’s allowed it in three years, and has allotted just 10 minutes for it, though in the end it’s more like five. “The last guy I had was a fucking dick. He wanted to be artsy fartsy,” he tells the photographer, Mike McGregor. “You’re okay.”

The Black Swan spent a whopping 17 weeks on the New York Times’ bestseller list.

Being artsy fartsy, I will learn, is even lower down the scale of Nassim Taleb pet hates than journalists. But then, being contradictory about what one hates and despises and loves and admires is actually another key Nassim Taleb trait.

In print, the hating and despising is there for all to see: he’s forever having spats and fights. When he’s not slagging off the Nobel prize for economics (a “fraud”), bankers (“I have a physical allergy to them”) and the academic establishment (he has it in for something he calls the “Soviet-Harvard illusion”), he’s trading blows with Steven Pinker (“clueless”) and a random reviewer on Amazon, who he took to his Twitter stream to berate. And yet here he is, chatting away, surprisingly friendly and approachable.

When I say as much as we walk to the restaurant, he asks, “What do you mean?”

“In your book, you’re quite…” and I struggle to find the right word, “grumpy”.

He shrugs. “When you write, you don’t have the social constraints of having people in front of you, so you talk about abstract matters.”

Social constraints, it turns out, have their uses. And he’s an excellent host. We go to his regular restaurant, a no-nonsense, Italian-run, canteen-like place, a few metres from his faculty in central Brooklyn, and he insists that I order a glass of wine.

“And what’ll you have?” asks the waitress.

“I’ll take a coffee,” he says.

“What?” I say. “No way! You can’t trick me into ordering a glass of wine and then have coffee.” It’s like flunking lesson #101 at interviewing school, though in the end he relents and has not one but two glasses and a plate of “pasta without pasta” (though strictly speaking you could call it mixed vegetables and chicken) and attacks the bread basket “because it doesn’t have any calories here in Brooklyn”.

But then, having read his latest book, I actually know an awful lot about his diet. How he doesn’t eat sugar, any fruits which “don’t have a Greek or Hebrew name” or any liquid which is less than 1,000 years old. Just as I know that he doesn’t like air-conditioning, football mums, sunscreen and copy editors. That he believes the “non-natural” has to prove its harmlessness. That America tranquillises its children with drugs and pathologises sadness. That he values honour above all things, banging on about it so much that at times he comes across like a medieval knight who’s got lost somewhere in the space-time continuum. And that several times a week he goes and lifts weights in a basement gym with a bunch of doormen.

He says that after the financial crisis he received “all manner of threats” and at one time was advised to “stock up on bodyguards”. Instead, “I found it more appealing to look like one”. Now, he writes, when he’s harassed by limousine drivers in the arrival hall at JFK, “I calmly tell them to fuck off.”

Taleb started out as a trader, worked as a quantitative analyst and ran his own investment firm but the more he studied statistics, the more he became convinced that the entire financial system was a keg of dynamite that was ready to blow. In ‘The Black Swan’ he argued that modernity is too complex to understand and “Black Swan” events – hitherto unknown and unpredicted shocks – will always occur.

What’s more, because of the complexity of the system, if one bank went down, they all would. The book sold 3 million copies. And months later, of course, this was more or less exactly what happened. Overnight, he went from lone-voice-in-the-wilderness, spouting off-the-wall theories, to the great seer of the modern age.

‘Antifragile’, the follow-up, is his most important work so far, he says. It takes the central idea of ‘The Black Swan’ and expands it to encompass almost every other aspect of life, from the 19th century rise of the nation state to what to eat for breakfast (fresh air, as a general rule).

As you might suspect, it’s a great baggy, idiosyncratic doorstopper of a book. Reading it, I spend the first 200 pages or so mildly confused. “I couldn’t figure out what genre it was,” I tell him.

“Forget the genre!” he says. I’d been expecting a popular science-style read, a ‘Freakonomics’ or a ‘Nudge’. And then I realised it’s actually a philosophical treatise.

“Exactly!” says Taleb. Once you get over the idea that you’re not reading some sort of popular economics book and realise that it’s basically Nassim Taleb’s Rules for Life, it’s actually rather enjoyable. Highly eccentric, it’s true, but very readable and something like a chivalric code d’honneur for the 21st century. Modern life is akin to a chronic stress injury, he says. And the way to combat it is to embrace randomness in all its forms: live true to your principles, don’t sell your soul and watch out for the carbohydrates.

What’s more, for all the barmy passages involving an invented character called Fat Tony engaging in a Socratic dialogue with another invented character called Nero Tulip (a very thinly disguised Taleb) and the fact that at one point he does actually seem to compare himself to Jesus – they’re both prophets who came from the East – he does talk a lot of what I can only describe as sense.

His justification for all this is that “experience is devoid of the cherry-picking that we find in studies”. More than anything else, he believes in having “skin in the game”. When, for example, he warned about the fragility of the banking system in ‘The Black Swan’, “I was betting on its collapse”. His point is that he’s always put his money where his mouth is, and it’s this principle – and the lack of it – that is still, he believes, the fundamental problem with the entire banking system.

In the book he calls this “Hammurabi’s Code”, a 3,800-year-old Babylonian law stipulating that if a building collapses and kills someone, the builder should be put to death. Whereas for bankers, “there is no downside”. The bonus system means that “they’re paid billions in compensation”. And if their bets lose, it’s the taxpayers who pay.

He cites, not unadmiringly, the tradition in Catalonia where they would “behead bankers in front of their banks”. So, what’s changed, I asked, since he wrote the book, and the system collapsed?

“Nothing. Nothing has changed. Zero. Now I switch to writing technical papers. There is some hope, the Bank of England wants to implement antifragility. Mervyn King [the governor of the Bank of England] spoke about it at the LSE. And I’ve done work for the IMF…”

But nothing’s changed?

This latest Taleb book investigates what the author calls antifragility. Basically if something is fragile, it’s damaged by an unexpected shock. If something is robust, it is able to withstand it. But to be antifragile is to be able to benefit from such a turn of events.

“I no longer care about the financial system. I gave them my roadmap. Okay? Thanks, bye. I’ve no idea what’s going on. I’m disconnected. I’m totally disengaged. People read 3 million copies of ‘The Black Swan’. The bulk of them before the crisis. And people love it. They agree with it. They invite me to dinner. And they don’t do anything about it.”

“You have to pull back and let the system destroy itself, and then come back. That’s Seneca’s recommendation. He’s the one who says that the sage should let the republic destroy itself.”

But doesn’t that frustrate you?

“It did. Now it doesn’t. But if you continue talking about it I will get frustrated, so let’s switch.”

He means it too. There’s a bit of an edge to the statement, so I ask him about David Cameron instead and he immediately relaxes. “He’s a great guy,” he says. There’s some sort of mutual appreciation that goes on between the modern Conservative party and Taleb. He name-checks Steve Hilton (Cameron’s former head of strategy) and Rohan Silva (one of his special advisers) and says they’re “buddies”.

“We had lunch once and realised we were talking the same language and it went from there. I never mention it in anything.”

Well, actually, I say, you mention it in the book.

Fraser Nelson, the editor of the Spectator, says that Taleb “is probably the closest thing Cameron has to a guru”. Why does Taleb think that is?

“Because they care about risk. Labour don’t care.”

And have they done anything about it? “I don’t know. I don’t read the papers. I provide intellectual backing for some principles, taking into account bigger risks with size and debt. With debt they have the arguments, they don’t need me. For size, I have the arguments.”

The “arguments” are that size, in Taleb’s view, matters. Bigger means more complex, means more prone to failure. Or, as he puts it, “fragile”. It’s what made – still makes – the banking system so vulnerable, in his view. It needs to be more “antifragile”. This isn’t the same as robust, he explains, which means it can simply take the knocks. “Antifragile” is when something is actually strengthened by the knocks.

He gives all sorts of examples of this in the book. A clerk in a large company is fragile as he has only one source of income. A taxi driver is antifragile. A banker is fragile. A prostitute is antifragile. General Petraeus is fragile: a single indiscretion was enough to destroy his career. Boris Johnson is antifragile: a whole string of scandals has actually enhanced his reputation. “He’s smart enough to present himself as sort of ‘This is how I am’,” says Taleb. London, too, seems to be antifragile. The global financial crisis was just another boost: a safe haven for foreign real-estate cash.

In Taleb’s view, small is beautiful. Corporate mergers never work. “It’s not a good idea being large during difficult times.” And, when companies think otherwise, it’s the “hubris hypothesis”. After reading this section of the book I flick to the cover to check who printed it: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin. Which has recently merged with Random House to create one big mega-publishing company.

“Your publishers haven’t actually read your book, have they?” I say. “If they’re smart enough they can keep the companies separate,” he says, not very convincingly.

In ‘The Black Swan’, one of Taleb’s great examples of non-linearity, or Black Swan behaviour, was Blockbusters. There’s no predicting what will be the next breakout success, or next year’s 50 Shades of Grey, but when they take off, they fly off the charts, as ‘The Black Swan’ did. The book itself was a Black Swan phenomenon. As Taleb is fond of pointing out – and as the small print beneath advertisements for mutual funds states – past performance is no indicator of future growth. Penguin seemed to have overlooked this point too since they paid him an astonishing 4 million USD advance for this book.

“They made a lot of money from ‘The Black Swan’ so to them it’s not too bad a risk,” he says, but I feel it’s more a guest’s politeness towards their host than anything else. Anyway, the money was not, he says, “a major part of my income at the time”. In 1987 he made a great deal of money shorting the financial crash and millions more during the 2008 meltdown. It’s his “fuck you” money that allows him to do exactly what he wants, when he wants, beholden to no one.

Most people would say, “It’s alright for some,” I point out. We’d all like that kind of independence. “That’s a false dilemma,” he says. And claims that a caretaker also has that kind of independence. “He can say what he thinks. He doesn’t have to fit his ethics to his job. It’s not about money.” Hmm, well, up to a point.

We’re perhaps not all quite as independent as Taleb, who writes about how, as a trader, on his first day in a new job, he wrote his resignation letter and placed it in his office drawer. What’s more, while a lot of people are rich because they like money and want more of it, Taleb doesn’t actually seem to be one of them. Most people, however wealthy, like to be paid for doing their job. But not Taleb. He doesn’t actually take a salary from NYU. “Well, I keep the minimum. I give back the rest. So if, tomorrow morning, they say ‘fuck you’, I’m gone.”

Then again this may be because as well as hating journalists and bankers, he’s almost as damning about academics.

“But you are one!” I point out.

“Not really. I’m an independent scholar, practically speaking.”

He’s also largely an autodidact. He has higher degrees but most of his working life was spent outside academia and much of his thinking is rooted not in 21st century mathematics but in the Classics. He quotes them endlessly, hero-worships Seneca and refers to himself as a “stoic”.

Not everyone, it has to be said, is a fan of the high style. Jamie Whyte in Standpoint magazine reflects the criticism of many when he accuses Taleb of “inflating” the significance of his observations with “an absurdly combative and grandiose writing style” and points out that publishing a book of aphorisms, as Taleb did last year, is “usually completed by someone else after one’s death”.

But Taleb is not someone who lacks confidence. He was born and brought up in Lebanon, his family rich and influential Greek Orthodox believers, a minority religion even in a country of minority religions. His grandfather and great-grandfather were deputy prime ministers and his great-great-great-great grandfather was the governor of Ottoman Mount Lebanon.

In ‘Antifragile’ he tells a story about his father, a doctor, a scholar and man with “a large ego and immense dignity who commanded respect”. At some point during the civil war, he stopped at a checkpoint where a militiaman treated him disrespectfully. “My father refused to comply and the gunman shot him in the back.”

It’s a pretty astonishing story and when I ask Taleb about it, he says: “I have very similar stories, too, but I chose not to tell them.”

“What do you mean?”

He prevaricates and then talks about “personal stories about taking a stand but I don’t want to wander into near-eastern politics”.

“Have you ever considered a political career?”

“No. But if you see my bio, there are missing parts. The Lebanese war. I’ll leave it at that.”

He won’t tell me anymore and it’s a bit of a mystery. He writes how, as a teenager, he was jailed for assaulting a policeman during a student riot and his entire family were “scared” of him. When war broke out, he initially stayed in Beirut, then left, but then came back again. But he won’t tell me what he did.

It’s too neat a formulation to ascribe Taleb’s Lebanese upbringing and his war-scarred teenage years as the source for his theories on randomness and instability. Malcolm Gladwell profiled him in the New Yorker more than a decade ago and attributed his belief in “Black Swans” to having experienced them – not just in the Lebanese war but also in a bout of non-smoking-related throat cancer.

But Taleb shakes his head. “That article was wrong about me,” he says. “That’s why you think I’m gloomy.”

“I didn’t say you were gloomy,” I say. “I said you were grumpy.”

“But anyway, these guys who think the same as me, many of them are from the Midwest. It’s much more to do with somebody’s temperament rather than their experiences.”

When the financial journalist Michael Lewis profiled a collection of individuals who, like Taleb, saw the crash coming and shorted the market, he described them as “social misfits”. It takes a certain sort of personality to stand apart from the herd. And Taleb’s cantankerousness, his propensity for picking fights and for taking stands does also seem to be the source of his greatest triumphs. It was horrible, though, he says.

“Really horrible. Between 2004 and 2008 were the worst years of my life. Everybody thought I was an idiot. And I knew that. But at the same time I couldn’t change my mind to fit in. So you have this dilemma: my behaviour isn’t impacted by what people think of me but I have the pain of it.”

“People made fun of me. I don’t know if you can still find it on the web but you would not believe how much crap was written about me. The finance industry hates me with a passion.”

“You must have felt incredibly vindicated?”

“Vindication doesn’t pay back. Nobody likes you because you were right. This is why I’m glad I made the shekels.”

Anyway, Taleb is a fighter. And like the Roman generals, he believes in going into battle, leading from the front. It’s why he thinks Tony Blair is a coward and a knave: “He’s a very dishonourable fellow. Gordon Brown is an idiot. But Blair was dishonourable.” He believes that people should be banned from making money from having been in public office. And he especially despises journalists who made the case for war on Iraq, like the New York Times’ Thomas Friedman, “a serial criminal” who he says makes him feel physically sick.

It’s back to his “skin in the game” beliefs. If you’re going to make the case for war, you need to have at least one direct descendant who stands to lose his life from the decision. And while some may wonder why they need a lecture on ethics from an ex-city trader, it’s hard to argue with. Though it’s easy enough to argue about more or less anything else. He won’t confirm or deny the existence of a Mrs Taleb. And he has a son and daughter “who are exactly like me” – but that’s all he’ll say about them. “I’m a private intellectual, not a public one.”

“But you write about parenting at one point,” I say. “And you’ve written a book about how to live.”

“Exactly. Here’s how to live: keep your public life separate from your private life.”

He makes me order tiramisu and then eats half of it but then no food has passed his lips for about 17 hours, he says. Incorporating randomness into his life has led him to adopt the style of eating known as “paleo”. Roughly speaking, this means that if a caveman wouldn’t have eaten it, then you don’t. Except tiramisu. And intermittent fasting is recommended as a way of mimicking the effects of, say, failing to catch a sabre-toothed tiger.

What’s more, he says, he goes to bed at 8pm and gets up at 4.

“Like a dog,” I say.

“Unless I go out.”

He’s throwing a party for his students the next night “to get them drunk”. With what aim? “No aim. They’re just so uptight.” He loves parties “but with close people. Not with hotshots. Not some black-tie dinner where you’re sitting next to some schmuck who’s going to tell you what he paid for his swimming pool. And not artsy fartsy. I can’t stand artsy fartsy.”

“But isn’t it hypocritical to be so anti-artsy fartsy when you are artsy fartsy?”

“I’m not. I’m mathematical not artsy.”

“But you go on about your private library. You say you spend at least 30 hours a week reading. You love the classics.”

“Yes, but it doesn’t mean I’m artsy. I don’t hang around with artsy people. I have zero literary friends.”

I wouldn’t want to get into a Twitter catfight with Nassim Taleb. Or be a banker in the audience when he gives one of his talks. “They pay me tens of thousands of dollars to come and rip them apart.”

But he gives good lunch. And he does something that no interviewee in the history of interviews has ever done – he pays. Whatever else he does or doesn’t do, Nassim Taleb puts his money where his mouth is. He has skin in the game. That, or it’s another example of “fuck-you money”. Possibly both.