With his infectious enthusiasm and meticulous approach to creative solutions, Crescent Enterprises’ CEO Badr Jafar, makes changing the world look easy as pie.

With his infectious enthusiasm and meticulous approach to creative solutions, Crescent Enterprises’ CEO Badr Jafar, makes changing the world look easy as pie.

Envision the archetypal modern-day social entrepreneur: you’re likely conjuring a kind of capitalist Robin Hood, someone looking to solve humanity’s problems with creative and economically sound solutions, who’s as motivated by doing good deeds as by robust financial rewards. The name Blake Mycoskie, the man behind Tom’s, a company that has donated 60 million pairs of shoes, restored eyesight to over 400,000 people, and given over 335,000 weeks of safe water to those in need around the world, might spring to mind. Or perhaps you’d think of Jeffrey Hollender, the founder of Seventh Generation, a company specializing in the production of eco-friendly household products founded in the 1980s that was generating over 250 million USD annually by 2016 when it was acquired by Unilever for 700 million USD. But an oil and gas magnate with a conscience? That might seem a little farfetched.

Yet that’s exactly what Badr Jafar, Crescent Petroleum’s President is. So what does a 39-year-old Eton and Cambridge educated second-generation energy exec have in common with the two aforementioned change-makers? It has to do with an indomitable drive to make things work better, or as he might put it, having bees in his bonnet.

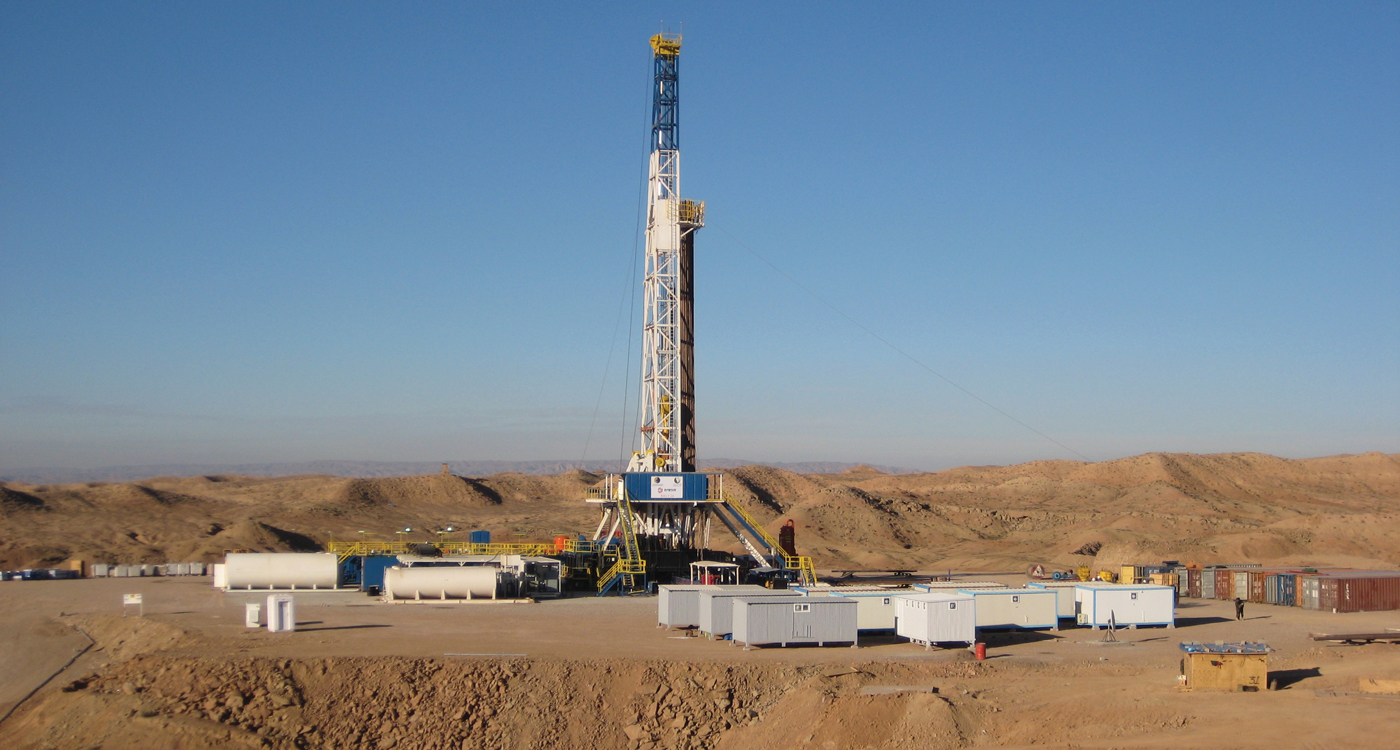

The social aspect of his entrepreneurship is something he talks about highly eloquently and armed with plenty of facts and figures, straight on the heels of a newly inked, 20-year gas sales agreement between Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government and Pearl Petroleum, a U.A.E. consortium which he chairs that includes Crescent Petroleum and Dana Gas (an independent, sustainable practice gas company in which, notably, Crescent Petroleum is the largest single shareholder. “We now produce 400 million cubic feet of gas per day, or 106,000 barrels equivalent per day if you convert the gas plus the LPG’s and the condensate in one aggregate figure,” and we’re going to boost production to 900 million cubic feet of gas per day in the next three years, specifies this Emirati businessman of Iraqi descent. “We’re currently meeting the majority of power needs for the five million people or so in the region, and this deal will create opportunity for new communities and industrial activity.” He’s also quick to point out that that the gas they produce is a step change for Northern Iraq, and a better alternative than what’s still being used to power other parts of the Middle East. “Before gas was produced, most of that power was being generated by liquids. Because gas is much cheaper, there’s no more need for subsidies and we’ve saved the government there over 20 billion USD over the last 10 years or so. And gas produces six times less CO2 emissions, which means we’ve saved millions of tonnes of carbon emissions as well,” he points out.

But that’s all Business Executive talk. What really gets Jafar going are the other projects on his plate, including some pretty disruptive non-profit projects: SME4H.com is the platform Jafar and his team have developed to help connect local small and medium enterprises with humanitarian organisations in crisis zones.

THE REALITY IS, I INVEST MONEY AND I APPLY THE SAME PRINCIPALS IN NON-PROFITS AS I WOULD IN MY FOR-PROFIT BUSINESSES. WHY WOULDN’T I?

“On our advisory board, there’s a Haitian who ran a very successful solar panel business in Haiti. When the earthquake struck and there was no power, and Haiti was flooded with capital to address the problems faced, he said ‘I can produce these panels’. So they asked him to fill out the ususal stacks of paperwork, and he filled them and submitted them to everybody, but they ended up procuring all of the equipment from big, external corporations. Not only was some of the equipment not fit for Haiti and its climate, but also it killed his business and forced him to sack 250 people. The humanitarian aid system is not set up for local procurement,” he explains.

The online platform is currently preparing to pilot the project in Jordan, and Jafar says it has already grown to a community of a thousand SME’s in that country alone. It’s obvious he’s eying a global network, though, and the biggest barrier, he says, is spurring change in the way big humanitarian organisations like UNHCR, Mercy Corps, ICRC, Rescue ON World Food Program and Save the Children do business.

“There’s inherent distrust embedded into many sectors globally that impedes change and the humanitarian sector is no different,” he says. “But this is an example of how an individual, or a group of people, can help to create, with technology, a solution to do things better, more efficiently and with higher impact than what was been done before,” he remarks. That – individual responsibility – is a topic he discussed as a panellist at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland in January, during a public session entitled ‘The Family Business Case’. It’s worth pointing out here that Jafar is also a member of United Nations Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing to develop solutions for the growing humanitarian finance crisis, and of the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) Private Sector Advisory Council, because well, that’s another way you can help get rid of the bees in your bonnet.

One of his latest not for profit entrepreneurial adventures is Hasanah, a global Islamic digital philanthropic platform he’s developing to help improve the effectiveness of Islamic giving. Between zakat and sadaka, 300 billion to a trillion USD is deployed globally every year, according to the World Bank and IDP numbers. The problem here, Jafar says, is that there’s a lack of transparency as to where the funds are going.

One of his latest not for profit entrepreneurial adventures is Hasanah, a global Islamic digital philanthropic platform he’s developing to help improve the effectiveness of Islamic giving. Between zakat and sadaka, 300 billion to a trillion USD is deployed globally every year, according to the World Bank and IDP numbers. The problem here, Jafar says, is that there’s a lack of transparency as to where the funds are going.

“When you watch TV and you wonder how all these non-state actors are getting funded, I would not be surprised that some of their funding comes from money that started on its journey with the right intentions but because of the lack of proper mechanisms, it finds its way into the wrong hands and has unintended consequences,” he says. So to address this, he proposes a platform that harnesses the power of Islamic giving by connecting alms givers with end users. It’s ambitious, he admits, but it would admittedly be hard to find a reason not to develop and use such a platform, and he expects the project will have organic growth, the kind that social platforms like Facebook had, once the pilot launches by the end of 2019.

Entrepreneurship, of course, is a risk and reward game, and sometimes the rewards are quite simply more easily measured when they come in financial form. Which is where Jafar’s Crescent Enterprises comes in. As CEO, Jafar overseas this diversified business, which employs about 6,000 people in a wide array of sectors, including Gulftainer, a ports and logistics company that operates globally, including in the Middle East and the US. In March, it signed a new a 50-year lease agreement with the state of Delaware, pledging to invest more than 580 million USD into the port when it signed. That, along with some business aviation and other logistical and engineering enterprises is part of CE-Operates, one of four core verticals. CE-Invests, CE-Ventures, and CE-Creates each serve their own purposes, and it’s the latter that seems at the top of his mind this particular afternoon.

CE-Creates opened Kava & Chai in 2017, Jafar’s idea of a homegrown, sustainable coffee shop brand, which already has four locations across the UAE and plans for expanding into the US and UK markets. It’s one of several internal ventures the incubator is currently hard at work on: there’s also Shamal, which is developing next-generation industrial uniforms designed for hot and humid climates. The idea came to Jafar last February when he noticed workers in his building were soaked with sweat after just a few moments attending to something on the roof. After trying in vain to remedy the situation with some new uniforms, it became apparent that there were no real alternatives to the standard issue, thick uniforms so he set about some serious R&D and initiated hundreds of focus groups with labourers and foremen. “Turns out that in addition to the comfort aspect, they also want to look good, they want a sense of pride. All of these buildings around us would not exist without these workers. So why aren’t we recognising them with better uniforms, like say firemen or policemen?”

Jafar expects this is something that will resonate with construction companies looking to increase productivity thanks to happier workers (Jafar says he’s already collected data on the veracity of this). And he plans to take this one global, too. He decries the fact that despite the fact that the Middle East has 500 million people, you’d be hard pressed to find a brand from the region in any other part of the world. If these last two projects stay the course, there goes another bee.

It would be too much for most, but Badr Jafar welcomes the symbiotic link that weaves all his ideas and projects together. “The premise is there has to be a very defined social impact, otherwise I’m not interested,” he admits. The other thing he won’t compromise on? All worthy enterprises should be treated equally. “The reality is, I invest money and I apply the same principals in non-profits as I would in my for-profit businesses. Why wouldn’t I? When I invest in a company that’s doing crazy things, some of which are working some of which are not, it’s because I see that the things that may work, even if they’re a small percentage, are going to change the world and become bigger than all their competitors.”