Though it’s just as beautiful, Lake Garda never became the playground for the wealthy that its smaller neighbour, Lake Como, did. Yet, now that a handful of starchitects have teamed up to create a unique ensemble of stunningly beautiful and expensive homes, it looks as if the nature of Italy’s largest lake is about to change.

Lake Garda, the largest lake in Italy, is one of those stunning, well-kept secrets of the north – home to just a few dusty hotels in the string of seaside towns that are huddled around the vast swathes of water. This was where Mussolini kept a villa for his mistress, and later on, his last bastion of power, the unofficial headquarters for his Italian Socialist Republic. It was also where the bizarre, pro-Fascist Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio built his surreal mansion turned state monument, the Vittoriale. It was a place of failed or lost ambition, wild dreams and what could have been. Times can change however.

Nowadays, there are two ways to experience the gorgeousness of this area. The first is on the water, as I did, speeding in a handcrafted mahogany boat – a few hours will take you across the Gardone Riviera, from the Gargnano harbour to Salo. Here, you can admire the dark sculptural Baldo mountains that rise magnificently above the lake’s crystalline waters, the cypress trees towering like spires amongst the charming Art Nouveau pastel rose and honey-coloured houses, the cascading bougainvillea, and a succession of hills in an endless canopy of green. Or, you can journey through the headlands, snaking through the winding pathways by car until you reach Villa Eden, on the southwestern lakefront overlooking Gardone. It is here that you’ll find a cluster of luxury villas by some of the world’s leading architects, which, we think, will probably transform the way in which the entire area is perceived.

Then again, your tour of this new development might not start the way you’d expect it to – mine didn’t. For one, my first image is hazy, from the windstorms of sand particles that cloud my vision. It’s not as drastic as it sounds though for it is actually the turbulence created by a helicopter that’s taking 38-year-old Austrian developer René Benko to another of his homes. It might seem strange that the head of Austria’s largest real estate company, SIGNA, has chosen to develop his latest project here, investing close to 100 million dollars in the relaxed yet indulgent area but there may be more than just financial considerations at play considering he hails from Tyrol, the place where Austria and Italy collide.

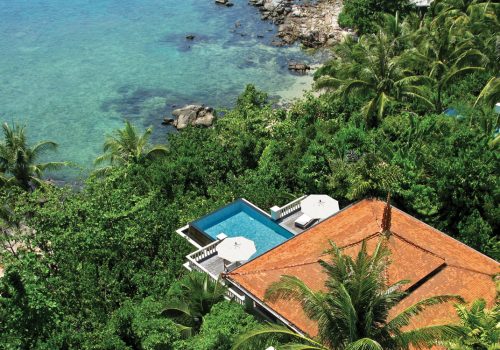

The Clubhouse’s spa pool overlooking the hills.

There are just seven villas in Villa Eden, perched on hills that dip steeply into the lake, and spread across 78,000 square metres of lush landscaping (Swiss landscape designer Enzo Enea did a fantastic job in transplanting all of the olive groves that originally grew here). If I were to describe the singular vision behind it, it would be that there isn’t an overarching one, as quite remarkably, there isn’t a single architect. In fact, there are four: (the Pritzker prize-winning American) Richard Meier, David Chipperfield (who’s best known for his epic museum buildings), the only Italian – Matteo Thun (originally famous for his work with the Memphis Group in the 1980s), as well as Marc Mark from the Austrian-German architecture and design firm ATP Sphere.

Now if you are wondering how Benko managed to gather such an eclectic team together, a clue is Innsbruck, the capital of Tyrol, where a few got the chance to encounter him (Chipperfield designed Benko’s department store there, the Kaufhaus Tyrol, and Sphere’s headquarters are actually based in the city).

They were all given just two rules to adhere to: no fences and no private gardens. As Harald Müller, from Chipperfield’s Berlin office explained on the site, “since everything is open from an architectural point of view, we wanted to balance the idea of having no fence, by enabling a space where you can hide a little so you’re not too exposed.” But while some architects sought spaces of shelter, others oriented their buildings to take full sweep of the surroundings.

“Benko wanted to involve different architects and different languages,” Thun tells us, in the Clubhouse, which has a glinting, stained glass façade in shades of green and blue, and which Thun has designed in addition to his villas, one of which is a delicate mix of natural stone, white plaster and glass sandwiched between two sheets so thin, they lend the effect of existing. somewhere between the realm of fixed and the floating. The second, named the Landmark building, comprises a staggered series of three penthouses, each with the ‘ground’ level completely submerged in the hill and the upper level stacked on top in a striking wooden box form. “When I told the politician in charge of the construction permits about my vision for a botanical form of architecture and integrating the buildings into the natural environment, he said to me, ‘why don’t you just take a risk and create a landmark?’” Thun continues, playfully. “But my idea was that the architecture should disappear. In critical positions, such as from a boat on the water, you shouldn’t see anything of the buildings.”

This reminds me of what David Chipperfield said to me, later in a phone interview. “The desire we have, as a practice, is to create a building that when it’s finished, seems like it belongs, like it should be there. These aren’t technical decisions; they are intellectual ones. The building, and the architecture is the thing that stays, even when everything else changes.” To compare his statement to Thun’s, you’d expect a very different kind of building to emerge, and you wouldn’t be wrong. Yet even in the project’s espousal of difference and a range of styles, it has still managed to create an environment in which the villas stand as well independently, as they do together.

And in several cases, you will have one villa divided into two or three buildings, separated by a pool – there’s one for the spa alone for example, another for the living area, and Chipperfield even created a separate guesthouse.

Though all the buildings couldn’t be further from the Belle Epoque style prevalent in Garda, Chipperfield did take some inspiration from the architecture originating in the region in the 18th century; his villas are anchored by very high, slender columns on their façades, reminiscent of the ancient ‘limonaia’ greenhouses used to protect the lemon trees. “We were fascinated by these regional structures that previously existed to grow lemons – they were a form that fit into this kind of landscape,” he tells me. I remark how the pillars have the effect of slicing the view into sections. Chipperfield counters, “We had this anxiety of making a luxury house that ends up looking like a glass structure, so we wanted to avoid the cliché of big glass windows – the bigger view isn’t always the best view.” What the columns have also done is create a shaded pergola structure between the inside and the outside, which is an interesting in-between space to experience on site, an ‘interstitial’ space, as Chipperfield puts it. “The building has to have its own landscape too, it’s not just a window to the outside, the house transforms from the inside to the outside.”

Mark, from Sphere, on the other hand, went in another direction, “We wanted to work on the tension between having a modern house in an ancient, classical Riviera atmosphere. In a way, it’s the opposite approach to Chipperfield – our houses are based on the inside and not on how they look on the outside. There’s this famous saying that you live in a house, you don’t look at a house. In other words, you cannot understand a house at first sight, you need to move through it.” And quite unusually, one of Sphere’s three villas that we visited, was accessible only through an underground postmodern garage-turned living space, before you rise via a lift and come face to face with an ocean of space and light that is the expansive, combined living and dining area.

Mark, from Sphere, on the other hand, went in another direction, “We wanted to work on the tension between having a modern house in an ancient, classical Riviera atmosphere. In a way, it’s the opposite approach to Chipperfield – our houses are based on the inside and not on how they look on the outside. There’s this famous saying that you live in a house, you don’t look at a house. In other words, you cannot understand a house at first sight, you need to move through it.” And quite unusually, one of Sphere’s three villas that we visited, was accessible only through an underground postmodern garage-turned living space, before you rise via a lift and come face to face with an ocean of space and light that is the expansive, combined living and dining area.

Tastefully furnished, each with their own gardening and concierge service, these villas, which range between 10 and 15 million Euros (11 to 17 million USD), are somewhere between private luxury resort and holiday home. There’s also the added option of staying in one of the seven rooms or two Presidential suites at the Clubhouse, which is set to become a small five-star hotel.

Subtle and stylish, contemporary and comfortable, the property, which is expected to be completed next spring (construction began in 2012), is unobtrusive and elegant, a triumph of both glamour and intimacy, a lot of which is due to the breathtaking location. “When you come from the North, the first dream of South is here. For children, the lake feels like the sea. Lago di Garda is my dream of smoothness,” Thun had waxed lyrical when I asked him about his own relationship to the place.

“I think that in 10 years, the Clooney effect will be gone forever,” he added cheekily, since he heard the actor was selling his villa in Como. On second thought, maybe it’s a good thing the rich and famous haven’t gotten to Garda yet.

Photography: Courtesy of SIGNA