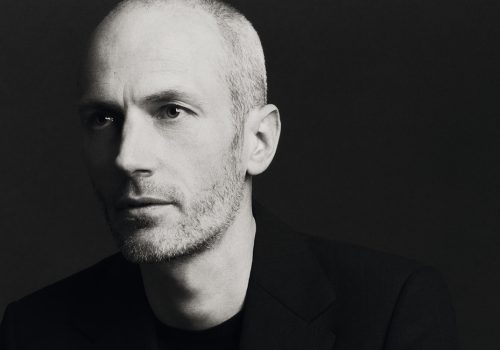

Over half a million visitors queued for hours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City this summer to witness a monumental, retrospective exhibition of the late British fashion designer Alexander McQueen’s astonishing body of work.

Over half a million visitors queued for hours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City this summer to witness a monumental, retrospective exhibition of the late British fashion designer Alexander McQueen’s astonishing body of work.

Alexander McQueen was obsessed with beauty and its decay. His macabre expressions were as terrifying as they were hauntingly profound, his clothes crossing and challenging the boundaries between spectacle and art. In honouring his work – McQueen committed suicide last February at the age of 40 – Andrew Bolton, curator of the Costume Institute at the Met, organised an exhibition, entitled ‘Savage Beauty’, which became the eighth most popular in the museum’s 141-year history. It was so popular, in fact, that its duration was extended with opening hours until midnight for the last two days of the exhibition. So unceasing was the demand that if you wanted to see the exhibit on Mondays, when the Met is usually closed, you could, for a 50 USD fee.

It all began with a tattoo. “Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind”, a quote taken from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream that once graced McQueen’s upper right arm. “The quotation seemed to encapsulate Alexander’s vision of fashion,” Bolton explains, “which reflected upon the politics of appearance by revealing both the prejudices and limitations of our aesthetic judgments. For McQueen, love was the most exalted of human emotions.”

McQueen himself did once admit to being “overly romantic” and it was the philosophical tenets of the Romantic movement and McQueen’s engagement with its concepts that formed the basis of Bolton’s categorisation of McQueen’s visceral work. “His fashions were often an outlet for his emotions, an expression of the deepest, often darkest aspects of his imagination,” the curator continues. “He was a true Romantic in the Byronic sense of the word – he channelled the sublime.”

Walking through the exhibition was like entering a confrontation with McQueen’s radical creations, which are as magnificent as they are jarring, “uneasy pleasures” as Bolton puts it. Whether influenced by the Gothic, by nature, by violence in the name of nationalism or the street (as in his low-lying bumster pants), there was something for everyone. Weaving through the loitering and captivated crowds, I found myself strangely alone, facing shredded lace. After several moments with this one piece, I was transported by the ruined innocence it evoked.

Entitled ‘Highland Rape’, the dress had been presented for McQueen’s autumn/winter 1995-96 collection. McQueen felt deeply connected to his Scottish heritage and the controversial assemblage did not refer to the rape of women, but rather to England’s historic pillaging of Scotland and more particularly, to the Jacobite Risings and Highland Clearances of the 18th and 19th centuries. It is believed, in retrospect, that it was this collection that established him internationally or as Trino Verkade, who ran McQueen’s studio, said “people then started to see him as an artist”.

From that point on, slashes and gashes became McQueen’s signature style. Think of Catherine Middleton’s royal wedding dress, designed by McQueen’s long-term assistant Sarah Burton, now head designer for the label. It’s a clear example of the dialogue between fashion and art that is embedded in McQueen’s work, iconic designs that as Thomas P. Campbell, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art put it, “constitute the work of an artist whose medium of expression was fashion”.

As the exhibition showed, McQueen displayed exceptional talent from the moment he started at London’s Central Saint Martin’s College. It included more than 100 masterful pieces dug out of his archives, from his very first graduate collection in 1992 – ‘Jack the Ripper Stalks his Victims’ – in which he introduced the origami frockcoat and locks of hair stitched onto every piece, to his final posthumous runway show ‘Plato’s Atlantis’, which was inspired by Darwin and displayed a decidedly futuristic aesthetic.

Often deriving his forms from the raw materials of nature, you could find dresses made from ostrich or duck feathers, strewn with flowers and sprouting horns. The exhibition also included references to the raven of death, to angels and demons.

Alexander McQueen was an extraordinary dramatist and his runway shows were legendary. Few people will forget the Kate Moss hologram in his 1996 ‘Widows of Culloden’ runway or 2005’s ‘It’s Only a Game’, a chess match between America and Japan, where each ensemble, from the 18th century waist-dress for the queen to the American football player with Japanese tattoos for the king, was designed to evoke a chess piece.

The exhibition’s scenography reflected this theatricality perfectly. Sam Gainsbury and Joseph Bennett (production designers who worked with McQueen on most of his fashion shows) were responsible for the six rooms, which were organised like chapters based on the romantic concepts central to the designer’s oeuvre. The first of these – ‘The Romantic Mind’ – featured concrete walls that sharply accentuated headless mannequins dressed in rigorously tailored and yet innovatively-cut outfits, coats, jackets skirts and pants that displayed a precise vocabulary of construction. Known from the start for his ingenuity in draping, McQueen’s first apprenticeship was on Savile Row, where he worked under Anderson & Sheppard, purveyors to the British royal family. His technique grew even more sophisticated during the five years he served as chief designer at Givenchy from 1996.

“It is this approach, at once rigorous and impulsive, disciplined and unconstrained,” says Bolton, “that underlies McQueen’s singularity and inimitability.”

The next room, ‘Romantic Gothic and Cabinet of Curiosities’, highlighted the designer’s fascination with all that was Victorian and melancholic, the dialectical oppositions of life and death, beauty and horror, using aged mirrors as a backdrop. The cabinet featured cubbyholes built into the wall, which harboured extravagant accessories. Most were designed in collaboration with renowned milliner Philip Treacy (his hat made from turkey feathers shaped like butterflies is of particular note) and Shaune Leane, who collaborated with McQueen on creating the disturbing, armour-like spine corset.

In ‘Romantic Nationalism’, the marquetry on the walls matched swatches of Scottish tartan, another of McQueen’s leitmotifs. If Highland Rape (1995-96) featured models speckled in blood spots to indicate Scotland’s bloody history, then ‘The Girl Who Lived in the Tree’ (2008-9) was the softer side of Empire, the dresses of the queens of England, quixotic and sardonic echoes of McQueen’s country house in Sussex.

‘Romantic Exoticism’ showed McQueen’s global eye and was replete with influences clearly derived from Asia and Africa – kimono collars and obi sashes. ‘Romantic Primitivism’ placed exquisitely distressed garments against a backdrop of rusted metal and wood, plastered in places with mud, horsehair, glass beads and other fetish objects. Finally ‘Romantic Naturalism’ juxtaposed McQueen’s last fully realised collection, ‘Plato’s Atlantis’, against the designer’s blown-up sketches and abstract imagery that suggested technology, creation and vagaries of space-time.

On the audio guide accompanying the exhibition, which featured the vivid recollections of more than a dozen close friends and colleagues in addition to a wealth of information about the late designer, Philip Treacy sums up the entire McQueen experience with eloquent succinctness: “He had this capacity,” the milliner says, with more than a touch of wistfulness in his voice, “to make ordinary people look otherworldly.”