Richard Rogers

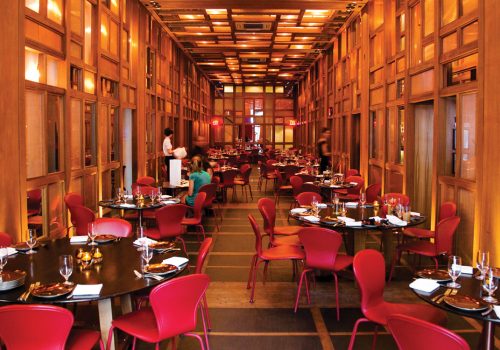

His work may divide opinion but there’s no disputing that Richard Rogers is one of the most influential architects of our time. Still, at 81 he admits he “can see an end coming” and has changed the name of his firm from Richard Rogers Partnership to Rogers Stirk Harbour+Partners so that his work ethic and spirit may continue well after he has left the building.

“I think I’m just old enough to face up to this!” A few months before his 82nd birthday, Lord Rogers, dressed in eye-catching orange mandarin-collared shirt, laughs nervously as he peers at a pair of college reports I’ve picked up from a table in his Hammersmith office.

This is strewn with archival material that formed part of a retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts in Piccadilly, ‘Richard Rogers RA: Inside Out’, a celebration of 50 years of radical ideas that have reshaped, and even revolutionised, modern architecture and ways of thinking about how we might live in ever-expanding cities.

The first of the reports, from the Architectural Association’s School of Architecture in London, dates from 1958. Signed by the no-nonsense architects and tutors, Michael Pattrick and John Killick, it fails the then 25-year-old Rogers in every category. “He has a genuine interest in and feeling for architecture,” it concludes, “but sorely lacks the intellectual equipment to translate these feelings into sound buildings.”

“I couldn’t have looked at this even 10 years ago without a shudder,” Rogers says. “I’d been failing – written off – academically since I started prep school in England. When I was six, I was beaten because I couldn’t memorise a poem. And I was still being beaten up at the AA 20 years later!”

Rogers, who had come to England from Florence shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War with his parents, Nino, an Anglophile doctor, and Dada, daughter of a civil engineer and an architect, spoke only Italian. His difficulty in coming to terms with the physically and emotionally cold world of the English public school system was compounded by severe dyslexia.

“I don’t think many people knew the word then,” he says. “I’m not sure if I can spell it now. I didn’t read till I was 11, and only really knew about it when my sons were growing up; they’re dyslexic, too.”

“When I was at school, art was for sissies, and I was always bottom of my class.” For one petty infringement, Rogers was forced to box with a much bigger and older boy. Field Marshal Montgomery, a school governor, watched as the punishment was meted out. “You did your best,” the desert hero told Rogers, “but you weren’t good enough.”

As for that second Architectural Association report, what a difference a year can make. Peter Smithson, a radical architect with a love of theorising, polemic and argument, saw in Rogers a charismatic young man with a pronounced ability to think about architecture and the ways it might impact on society through group discussion.

GLOBAL CAPITALISM DOES HAVE ITS GOOD SIDE. IT’S BROKEN DOWN BARRIERS – THE BERLIN WALL, THE SOVIET UNION – IT’S RAISED A LOT OF PEOPLE UP ECONOMICALLY, AND FOR ARCHITECTS IT HAS MEANT THAT WE CAN WORK AROUND THE WORLD.

Rogers, the most sociable of creatures, never wanted to be the solitary artistic genius (“I don’t know how to be alone,” he says). His particular skill has been to gather around him gangs of architects, engineers, thinkers and writers who have talked, as much as drawn, new forms of buildings into colourful and unexpected life.

“Peter [Smithson] got me, and things gelled somehow,” Rogers says. “I was still pretty useless at drawing [at one stage, his girlfriend Georgie Wolton did them for him] but I was full of ideas I wanted to share.” Smithson’s report helped Rogers win the student of the year prize, and was his passport to Yale University on a Fulbright Scholarship. He never looked back.

These days, Rogers takes his place as one of the world’s most celebrated, if most controversial, architects, a familiar name even to those with little interest in architecture, and the visionary behind some of the most instantly recognisable structures of the past half-century, including the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg and several London landmarks such as the Millennium Dome, the Lloyd’s building and Heathrow Terminal 5.

These days, Rogers takes his place as one of the world’s most celebrated, if most controversial, architects, a familiar name even to those with little interest in architecture, and the visionary behind some of the most instantly recognisable structures of the past half-century, including the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg and several London landmarks such as the Millennium Dome, the Lloyd’s building and Heathrow Terminal 5.

He has been well rewarded for his achievements and is now a firm member of the titled establishment. I used to wonder why this campaigning socialist, who has done much to promote the cause of civil rights, to champion organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières and to give active support to British Labour governments, chose to accept a knighthood in 1991. (At the time, he told me it was ‘for architecture’, and perhaps it was.)

Since then Rogers has become a peer of the realm (Baron Rogers of Riverside, created 1996) and a Companion of Honour. He was also awarded the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture, a gift of the Queen, in 1985, and was the first architect invited to give the BBC Reith Lectures, in 1995.

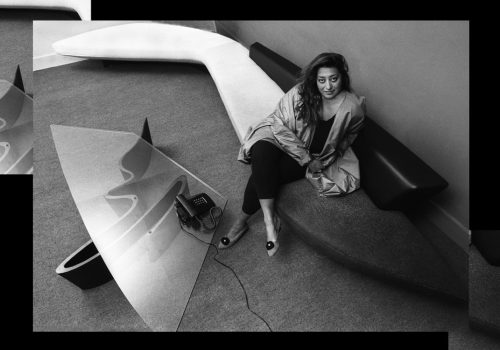

He became a Royal Academician in 1984, was a Tate Gallery trustee in the 1980s and, with the opening of the River Café – initially a Richard Rogers Partnership (RRP) staff canteen set up by Rogers’ second wife, Ruth, and her friend Rose Gray – he nurtured a meeting place, and a critically acclaimed restaurant, for what has since become the new establishment in politics, art and media.

The Lloyd’s building in London, above, and the Pompidou Centre in Paris, right, are leading exercises in radical Bowellism architecture in which the services for the building, such as ducts and lifts, are located on the exterior in order to maximise space in the interior.

This new establishment is not to everyone’s taste though. The Prince of Wales sees Rogers as a designer of ‘carbuncles’ and fought RRP’s 1987 competition plans for Paternoster Square – a redesign of the office precinct to the north and west of St Paul’s Cathedral. The architectural historian Gavin Stamp has raged against Rogers’ ‘relaxed’ style since the early 1980s; more recently, Stamp has described One Hyde Park, the controversial Qatari development of new Knightsbridge flats by Rogers, as “a vulgar symbol of the hegemony of excessive wealth, an over-sized gated community for people with more money than sense, arrogantly plonked down in the heart of London”.

The building that made Rogers’ name was designed not for the international rich, but for everyone. Indeed, in its first year, the iconoclastic Pompidou Centre – completed in 1977 – attracted six million visitors, making it more popular than the Eiffel Tower. At the time Rogers designed this radical public arts centre with Renzo Piano – a dashing young Genoese architect with a passion for innovative, yet skilled and crafted engineering and construction – and a talented gang of young architects and engineers, he was very much not a part of any establishment, old or new.

In 1960, when Rogers and his new wife, Su, also an architect, crossed the Atlantic on board the Queen Elizabeth, bound for Yale, a thrilling new world opened up that appeared to offer a gloriously democratic new order for everyone, from the huddled masses long welcomed by the Statue of Liberty to British citizens free at last from austerity, rationing, the worst of smog and National Service.

“I was just blown away by New York,” Rogers says. “We’d left Southampton looking down on streets with men in cloth caps riding bicycles, and now we were looking up at these amazing buildings. We hadn’t travelled as young people do today, so everything was new and utterly thrilling.” At Yale, Rogers fell in with Norman Foster, a graduate of Manchester University and already on the launch pad of a stellar career that would lift off back in London.

“Yale was wonderful after England,” Rogers says. “We went to see as many Frank Lloyd Wright buildings as we could and the stunning new ‘Case Study Houses’ in California.” Sponsored by John Entenza’s Arts & Architecture magazine, these were as far from neo-Georgian commuter homes in Surrey as they could possibly be: crisp, open-plan houses awash with ozone, ocean light and Miles Davis, they were “achingly cool” in the eyes of the young British students.

“It was the incredible optimism of American culture,” Rogers says, “that filled us with a kind of anything-goes energy. This was the era of giants like Louis Kahn and Eero Saarinen, and Mies van der Rohe’s wonderful Seagram Building on Park Avenue had only recently been finished. There was nothing like this confidence in England.”

Foster and Rogers were equally fascinated by the work of the young Ezra Ehrenkrantz, who was busy developing innovative systems for public and commercial buildings, designed to accommodate technical, social and structural change. Many of the ingredients that would produce, first, the Pompidou Centre and then Lloyd’s of London (completed 1986), the Bordeaux Law Courts (1998), the Millennium Dome (1999), and Madrid Barajas airport’s Terminal 4 (2005) were being prepared, if not yet mixed, sautéed and served.

Meanwhile, ideas that Foster and Rogers had been toying with while sharing a house in the US began to gel when the young architects returned to London and, as Team Four – Su Rogers and Wendy Cheeseman completed the quartet – designed a beautiful house, Creek Vean, set into the landscape of a Cornish inlet. This was for Su’s parents, Marcus and Rene Brumwell. They sold a Mondrian to pay for it.

“Norman and I did another house, for Tony Jaffe in Hertfordshire [the Skybreak House, Radlett, 1966; its interior is featured in a singularly nasty scene in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange], and a factory for Reliance Controls in Swindon. It won us an FT award for industrial architecture, but then we went our different ways.”

With its 48 floors stretching 225 metres high, The Leadenhall Building, popularly known as ‘The Cheesegrater’ due to its distinctive wedge shape, was designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners and completed in July 2014.

By now, Rogers was 36 years old with three sons, yet, aside from the design of a small, ultra-modern house and pottery studio for his parents in Wimbledon, he had very little work. At the same time, he fell head-over-heels in love with 21-year-old Ruth Elias, the vivacious daughter of a left-wing doctor and librarian from upstate New York, who arrived in London in 1967 ready to take to the barricades in Grosvenor Square. A divorce from Su followed, and Rogers appeared to be starting from scratch, in every which way.

Then something quite unexpected happened. Against his will, Rogers was persuaded by Renzo Piano and Ted Happold, a structural engineer with Ove Arup, to enter an international competition for the Pompidou Centre, a hub for contemporary arts and culture in the heart of Paris, a huge gesture of support to new experimental movements and fashions in art and music by the French government. But a national monument? A design named in honour of the right-wing Gaullist politician who had put down the 1968 événements on the streets of Paris in heavy-handed fashion?

“‘Pompidou? Pompi-don’t,’ we used to chant,” Rogers says. The project seemed like everything he was opposed to. Under pressure from his eager colleagues, Rogers gave way. “Lucky I did,” he laughs. “We sent off our proposal at the very last moment in June ’69. It was one of 681 entries. A month later, the phone rang. It was Renzo. ‘Vecchio,’ – he always calls me old man because I’m four years older than he is – ‘are you sitting down? We’ve won the Pompidou.’”

A combination of the new Pop ideas emerging in London in the 1950s and the warmth and richness of life in Italian city centres Rogers had cherished from his childhood, added to what he had experienced in the US, finally found expression in the design of the Pompidou. And despite initially being panned by most critics, who found it too much like an oil refinery, it was to make Rogers’ name.

“Renzo says we were the ‘bad boys’ of architecture, and we were a pretty scruffy bunch. God knows what the French thought of us. Looking like a bunch of hippies, we had to rush off to a black-tie party in Paris. When President Pompidou looked at the drawings, all he said was, “Ça va faire crier.” [This is going to make a noise.] But we moved to Paris for five years, it got built on time and within budget, and it was a big success, a cross – as I liked to describe it – between Times Square and the British Museum.”

The Pompidou – “a space, not a building,” insists Rogers – was soon hugely popular, and yet, après Pompidou… rien. The work dried up. After a thin year, the phone rang again. It was Gordon Graham, the business-minded president of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Graham had been speaking with Lloyd’s of London, recommending architects to dream up a concept for a new building – not a nuts and bolts design – for the City institution. Again, Rogers was unsure. After all, this was the world of the old establishment in excelsis, the old school tie, spotted dick and custard, and the very highest finance. And, yet, it was for Lloyd’s that Rogers and his team went on to shape one of the most special buildings the City has known.

“In some ways, it’s old-fashioned,” Rogers explains. “It’s hand-crafted, a building from the Xerox copier era rather than the computer age.” Like some Gothic, Blade Runner take on Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, the Lloyd’s building remains a remarkable achievement, somehow weaving itself into old City streets, markets and alleys while, at the same time, struggling creatively with them as a Baroque cathedral does over regimented Georgian streets. It took eight years to design and build, opening in 1986.

“Lloyd’s was a wonderful client,” he continues. “They gave us time, allowing us the gaps between decisions where the creative thinking gets done. Today, we’re asked to present designs in detail before anyone really knows what they want, which is pretty crazy.”

Over time, the Lloyd’s building has been well received by architectural historians and modern architects alike, and in 2011 was listed Grade I – putting it on a historical pedestal alongside designs by those masters of the English Baroque, Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor. After Lloyd’s, Rogers’ practice took off. Significantly though, in its present incarnation, since 2007, as Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, it finds itself ever busier with commercial buildings and speculative development in Britain and around the world, reflecting the fundamental change in architectural commissions that has come about as the polite public realm and old-school institutions have given way to the brash world of insatiable global capitalism.

“When I started out, nearly every architect I knew was working in public practice; that’s where the radical thinking was done. But, there’s always a danger of looking back as our fathers did and saying, ‘Things were better then.’ Architects design buildings; that’s what we do, so we have to go with the flow. And, even though I’m still an old Leftie, global capitalism does have its good side. It’s broken down barriers – the Berlin Wall, the Soviet Union – it’s raised a lot of people up economically, and for architects, it has meant that we can work around the world. We’ve got projects in China, Australia, Mexico, the States [including 3 World Trade Center, a new 80-storey skyscraper on the site of the Twin Towers], which is great during recession. In 1932, people [he means architects] jumped from the top of the buildings when it seemed there was no possible hope of work.”

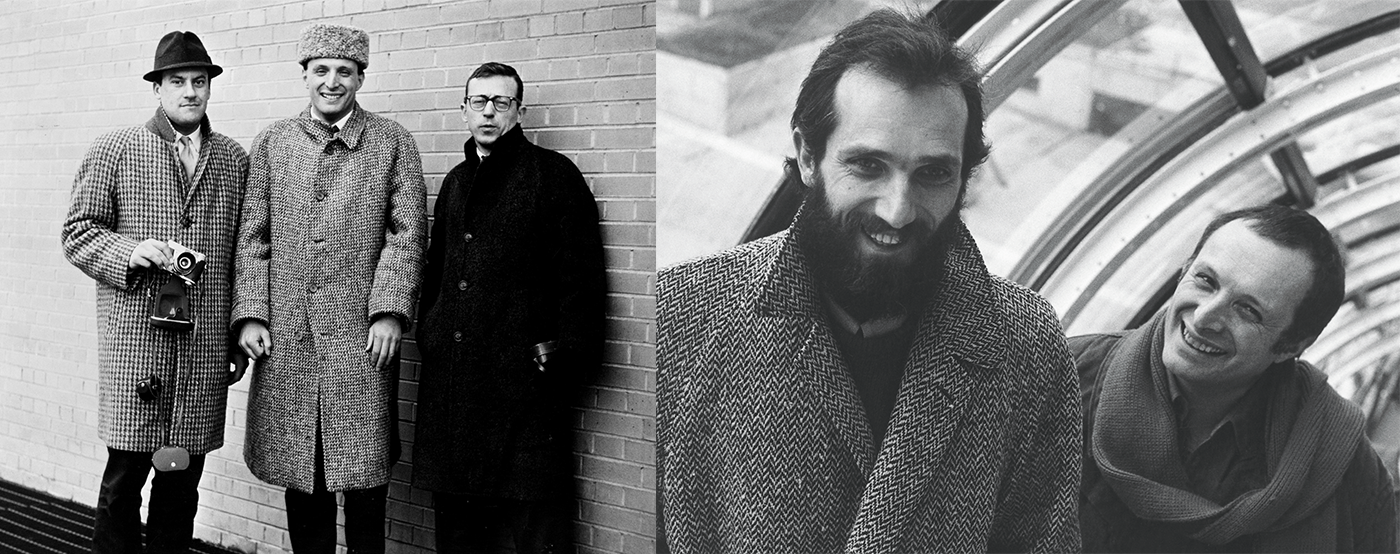

RIGHT: Norman Foster, Richard Rogers and Carl Abbott at Yale University in 1962. LEFT: Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers in 1977 at the unveiling of their landmark project in Paris, which was initially called the Centre Beaubourg until it was renamed Centre Pompidou after President Georges Pompidou’s death in 1974

Of the jobs that have eluded him, Rogers is philosophical. “I always prefer to look ahead. But you learn from the ones that got away; they’re in the back of your mind as you explore new projects, but they’re not things to regret. If you take The Leadenhall [aka the Cheesegrater, a striking and structurally expressive 48-storey skyscraper in the City of London], you’ll find a lot of the thinking we’ve done on urban design over many years. Where it meets the ground, it has a porosity that makes it a part of the streetscape; there’s a seven-storey public gallery at pavement level, with trees inside; it’s a speculative development with a civic smile.”

Rogers is an optimist, as all successful architects have to be. Surrounded by family – he has four children and 10 grandchildren at the last count – an extended family of well-connected and influential friends, business partners and colleagues, he has created a world very much of his own that has had a significant effect on modern architecture and urban design in Britain and around the world. The bad times – the break-up of his marriage to Su, the loss of his youngest son, 27-year-old Bo (who died suddenly and unexpectedly from natural causes while on holiday in Tuscany in November 2011), the apparent professional failure after the demise of Team Four and after the completion of the Pompidou Centre, and, of course, the memory of those 20 years of academic failure – he takes in his stride, publicly at least.

“My parents always told me that nothing was impossible,” Rogers says. “They gave me warmth and confidence that seemed at odds with the ups and downs I went through until, I suppose, I went to the States for the first time more than half a century ago. Then things really did seem possible. Not just for the architecture, but for a new way of life.” And, of course, for the people: the gangs – personal and professional – Richard Rogers has led, or been at the centre of, for half a century.

Rogers has no intention of slowing down. He laughs when I remind him that Oscar Niemeyer – who died a couple of years ago aged 104, and was busy until he could no longer hold a pencil – was old enough to have been his father. Rogers cycles, plays ball games and is restlessly alive, brimming with ideas for the future. “I’ll stop when I stop,” he says.

Many of the buildings that have gone up in his name have been provocative, epoch-defining creations. However, as the architect nears 82, the words of the great American architect Craig Ellwood echo down the years, and unequivocally into the future. “The purpose of architecture is to enrich the joy and drama of living.” Richard Rogers has certainly done that.