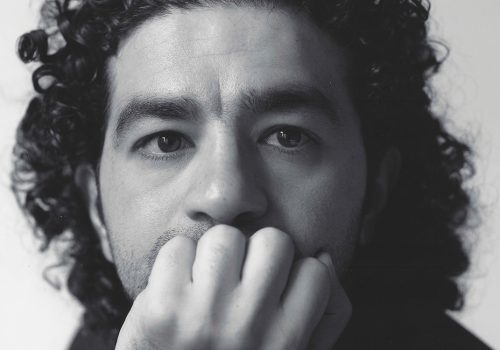

Rifaat Sheikh El Ard is unique amongst collectors of art from the Middle East. In an exhibition currently in show at the Institute du Monde Arabe in Paris, he and the Furusiyya Art Foundation have covered new historical ground and established original areas of interest and study of the arts of the Muslim chevalier or faris. Karim Munib discusses with the collector and his curator Bashir Mohamed, the collection, the Knightly Orders and the importance of re-investigating our heritage.

There are few collectors or collections in the Muslim world that approach the subject of collecting Islamic art and the arts of the knight. Hardly any collectors have altruistic aims, or interest in changing conventional perspectives. But Saudi businessman Rifaat Sheikh El Ard’s passion for and pride in Islamic Art has both these ideals in mind. This is perhaps due to him having spent a considerable amount of time in Spain during his childhood, from the age of eleven, where his Syrian-born father was appointed as Saudi Arabia’s ambassador. “There is so much Islamic history in Spain,” says the mild-mannered and extensively well spoken (he is fluent in Spanish and French) collector. “The Arabs were there for 800 years, so our influence was obviously great. This is where I began to focus on Islamic art.”

Rifaat Sheikh El Ard is by all accounts a self-effacing man, preferring to be in the background, to be judged through his work, his contributions to society and to his dedication to bringing into the fore the glories of our Islamic past. He is so keen not to be in the limelight and not to exposing himself as a person, that he gingerly requested that we focus instead on what appears to be his seminal work, a 1,000-plus collection.

Rifaat Sheikh El Ard is by all accounts a self-effacing man, preferring to be in the background, to be judged through his work, his contributions to society and to his dedication to bringing into the fore the glories of our Islamic past. He is so keen not to be in the limelight and not to exposing himself as a person, that he gingerly requested that we focus instead on what appears to be his seminal work, a 1,000-plus collection.

The collection is impressive, telling the tale of a man who took the painstaking time, in excess of a quarter of a century, to see his dream realised, and then to share it.

As with all astute businessmen he knew how to delegate, selecting the best, and never giving up until the job was accomplished. In the early 1980s, he teamed up with Malaysian-born Pakistani Islamic art expert, Bashir Mohamed, whose had a stellar reputation and unparalleled eye as a dealer and expert in this field.

Collector and consultant have managed to achieve quite a feat in bringing together this extensive and awe-inspiring collection of ‘cold’ weapons – those made of steel, hand-held and requiring person-to-person contact. The exhibition includes the rare items and weapons used by the Turkic al Arisiyya tribe (Kiev and Astrakhan are named after them), Muslim warriors who were the standing army and protectors of the Jewish kingdom of the Khazars. It is the descendants of these Khazars that are academically agreed to be ancestors to the Ashkenazis.

You also will be stunned by an even rarer dagger, a Crusader relic, bearing Arabic script as well as an icon of St. George. This unique dagger is attributed to a provenance from the kingdom of Jerusalem and, according to Mohamed, was made for the ruler of Jerusalem Norman Frederick II of Sicily following an agreement with Al Kamil, the Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt. “It is more rewarding, for me at least to collect objects and art that are related to our own heritage, those for which you have a kind of pre-ordained feeling,” says Sheikh Al Ard. Much like the knights he brings to life, Sheikh El Ard is on a quest to engender a positive and idealistic view of the Islamic culture.

WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO BECOME A COLLECTOR?

[RIFAAT SHEIKH EL ARD] Passion, without a doubt it takes passion.[chuckles]. You obviously also have to be patient and love what you are doing. It is an absorbing and exciting activity. Before I got seriously into the arts of the knight, I was already to a minor extent buying arms and armour and other Islamic art. But after a couple of visits to Sotheby’s and Christies and introduction to a couple of English dealers in arms and armour I began to ask myself whether I should make a concerted effort in any area. This is also the time when I was introduced to Bashir Mohamed, an art consultant based in New Bond Street at that time. We had some discussions about the collecting of Islamic art and in general during the period when I had already acquired a few choice pieces of Islamic art. It occurred to me at that time that although I ought to collect all areas of Islamic art, and indeed why should one ignore any particular area, many other collectors had already preceded me and swept up the major works of art in calligraphy, metal work, textiles etc and were still in the field! But I was also going to be competing with major museums the world over and in the Middle East. Moreover, the investment required in the well trodden areas was obviously going to be more than modest.

WAS IT AN EASY VENTURE TO PURSUE?

We both realised that is was not going to be easy, but I was secure with the knowledge that Bashir’s wide knowledge of Islamic art, his unfailing and keen eye, and above all his hunting skills would lead us somewhere, eventually. It should also seek to inspire others, by breaking new ground leading to increased study. By and large we have achieved that. Of the 1,000-plus items, out of which four hundred or so are shown in Paris now, there are very many that are historically ground breaking and academically interesting items. The fact that this early sector was untapped actually made it more difficult because the items needed were more than thin on the ground. Moreover we had an aesthetic standard. The items had to be works of art in every sense.

Right: Ottoman shield [XVI century] made from osier, textile and brass. / Top Left: Camel paraphanelia [XVII century] made from steel, silver and leather.

This is a philosophical question. There is no art for art’s sake in our culture. Everything useful is made beautiful, or as much as is possible according to the circumstances of the owner, or the artisan. And everything beautiful has also to be useful. Today, a collector has to train his eye to detect and separate the successfully beautiful from the everyday and normal.

It requires an in-depth understanding of the aim of such art, if one concedes that it has any aim at all. Academic art historians seldom go into these questions. One would be better off in this instance reading the works of people like Titus Bukhardt, Dr. Syed Hossein Nasr and the late Dr. Martin Lings. Incidentally, I have had many people who visit the exhibition tell me that they left the halls feeling that the works shown were beautiful works of art.

SO IS IT DIFFICULT TO TELL A FORGERY FROM THE REAL THING?

You have to have a background in Islamic art, in general and an additional background in the arts of other cultures will be even more helpful. One has to put in considerable study apart from acquiring considerable experience in handling objects of art. Every dealer has to put his money where his eye is and learn through mistakes.

HOW DO YOU SOURCE THE MATERIAL?

You need to have the right people around you to source the material. Luck also plays a part [chuckles]. I have friends who want to get into Islamic art and want to buy quantity. It is better to buy less and to buy quality even if this costs much more. Start with one great piece and work around that.

A pair of dastana [XVII century], made from Damascene steel, velvet and wood.

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF THIS COLLECTION?

I can say one thing, that there are many great, unique and priceless items in the collection-items belonging to great rulers like Bayazid the II, Sulaman the Magnificent’s grandfather, like the sword of Mohamed the Fifth, of Granada, the Prince who completed the building of the Al Hambra palace, and the sword of Tippu Sultan who many times defeated the British in India, and who was their nemesis.

WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SIMILAR ITEMS BELONGING TO CHRISTIAN KNIGHTS?

There are differences of manufacture and aesthetics. In some cases there are also similarities. On the whole European arms were mostly for cutting and stabbing, and are therefore double-edged and straight and pointed. After the ninth century onwards, Muslims began to increasingly rely on the curved sabre although the straight sword in honour of the Prophet was always kept. I feel generally that Muslim weapons tended to be more works of art than merely weapons; this is a personal opinion.

WHAT DO YOU THINK IT IS ABOUT ISLAM THAT MADE THE WEAPONS OF THE MUSLIM KNIGHT MORE ARTISTIC?

If one accepts this to be a fact then I would say firstly that the later weapons were more aesthetic than the earliest ones. Refinement came in after the ninth century, and continued to increase. I think this might well be because the idea of war was different for those rulers who were imbued with Islam and practicing it and not merely professing it. Christian Knights of course also fought for Christ and God. In contrast the Muslim knights who generally belonged to the many Sufi orders in Islam and who partook in the ghazwa’s seriously believed in Muslim chivalric ideals. And the Prophets son-in-law Ali was held up as the ideal Muslim knight. Hence the popular saying attributed to the Prophet, “There is no youth [knight] like Ali and no sword like Dhulfikar” The murabitun were self-sacrificing knights of North Africa including the Al-Muhadithun, both went on to found dynasties in Spain. Likewise many other orders when they sent their murids to so-called war sent them to spurred not by hatred of the enemy but with a love for the Creator and a readiness to sacrifice their lives for His cause, not with a sense of grief but with happiness. These kinds of soldiers were imbued with an ideal of beauty itself an attribute of the Creator. Naturally they would think of beautifying everything around them. Their weapon of preference was the yataghan, of which there is an excellent and luxurious example commissioned by the Sultan Bayazid Wali or Bayazid the Saint in the exhibition.

IS THERE ANY ITEM THAT HAS ESCAPED YOU?

Yes. The Dhulfikar sword given by the Prophet to Ali. But historically this sword disappeared sometime during the Abbasid period. Nobody knows where it is, but it must be somewhere out there to be found! By the way, contrary to popular belief, this sword did not have a double or bifurcated blade. Modern scholarship attests to it being a straight double edged sword with a notch in it.

WHAT IS YOUR FAVOURITE PERIOD IN ISLAMIC ART?

That is a difficult question because most periods have their great moments. I like the monumentality of the Ummayad period [661 A.D- 750 A.D] The variety and refinement of the Abbasid period as well as the Fatimid period [909 A.D-1171 A.D] One of the most prolific periods of great art was the Mamluk period in Egypt and Syria because the dynasty stretched over a very long period and many of their Sultans were great patrons of art.

WHAT IS LACKING IN THE WORLD OF ISLAMIC ART TODAY?

Firstly we don’t have any real patrons or at least not many of them. Our art is at its last gasp and not being promoted. It survives in little pockets, for example artisanal craft in Morocco, parts of Pakistan in some of the crafts and a little bit in Syria and here and there. It is virtually dead in Turkey and other countries. In spite of the fact that some of us are beginning to salvage and collect the old relics and artefacts and there are one or two serious museums being formed in the Middle East. Nevertheless Islamic art as such is not being promoted. Oddly more serious attention is paid to Islamic art and Islamic art studies in the West, and some of us are getting our inspiration from there. Maybe we have other priorities today, but I think it is important not only to know and learn about our past in our institutions, but from there we have to take it one step further in terms of the contemporary environment. We have to use the old principles in a contemporary context. We obviously can’t do that if we don’t even have a sense of the history and principles that governed our own art.

Left: Stitched and plated armour [XV century]. / Right: War mask from brass and silver [XVI century].