Much about Ahmed Mater’s world seems to reconcile opposing states of being. Somehow, the artist finds space for religion and science, anatomy and spirituality, technology and tradition, violence and morality, swarming multitudes and empty plots of land.

Speak with Ahmed Mater and almost immediately, you’ll get the sense that he is a humanist who believes in the potential of human goodness. Look at his artwork and you might find it projects a darker view. Take his ‘Evolution of Man’, for example. It’s comprised of five silkscreen prints. The first shows a skeleton (Mater’s own), pointing a gun at his skull. Gradually, it morphs in stages into a petrol pump. In the animated version of the piece, the pump also morphs back into the skeleton. This gesture of suicide, of our faceless dependency on oil and the general demise of mankind is rendered even more eerie by the blue-ish luminescence of the X-ray print.

“As I have mentioned before, I am the son of this strange, scary oil civilisation. And this is what the piece is about. It’s my most militant piece, yes, in saying we are destroying ourselves. But it is also a form of caring. Of raising awareness,” he tells me, emphasising that, at heart, he is still an optimist. “We are still here after all and we still have our values. Without them, we would be left with nothing.”

These values are something he plays with more explicitly in ‘Cowboy Code’, the idea for which Mater says he “stole from a Gene Autry song of the 1940s’. In it, he creates his own version of the Ten Commandments, writing them out using red, plastic gun caps. In one variation of the piece, exhibited in the Edge of Arabia’s ‘We Need to Talk’ exhibition, which took place in Jeddah earlier this year, the list was juxtaposed with similar sayings taken from the Hadith; of not harming women and children, of not being extreme or fanatic and of not taking unfair advantage of the enemy. “We have the same values,” Mater says with a smile I can almost hear over the phone. “Bedouins and cowboys.”

The artist’s convictions are earned. Growing up in Aseer, a mountainous region along the Saudi Yemeni border, he abruptly found all of his values called into question when he moved from his ancestral village to the regional capital, Abha, as a teenager. “They collapsed,” he confesses, without fully explaining what prompted this period of inner turmoil. “I tried to destroy all that I had assimilated. My rejection gave rise to experimenting with art.”

Not that art was a stranger to his life. Mater says he was always surrounded by it, albeit of a more traditional kind. His mother was both a calligrapher and a housepainter. Aseeri houses are known for their colourful decorations. Walls are painted with bright geometric, tribal designs, much like those used in rug-making.

A year after he enrolled in medical school, Mater began his artistic training at the Al Miftaha Artists’ Village, a state-sponsored initiative to encourage creativity. “My formation was more in drawing and painting in oils and acrylic but I soon started exploring more contemporary practices like photography, film and installation,” he explains. “If I wasn’t a doctor, I’d definitely be a filmmaker but in those days, filmmaking wasn’t being taught in university here. If you think about it though, an X-ray is like a film. You just capture the particular still or moment that strikes you.”

When I ask him how he developed the idea of using X-Ray prints in his work, he says he doesn’t remember. “The art-making process is very abstract and instinctive. You just need to have this confidence to take or extract something that normally has another life and put it in your art.”

He has used that confidence to start a number of grassroots movements in Saudi Arabia’s art scene. In 2004, he started the country’s first contemporary art movement, Shattah. A year later, he and colleague Stephen Stapleton started Edge of Arabia, which supports and promotes contemporary Saudi Arabian artists worldwide and in 2006, he set up an association for artists in Aseer called Ibn Aseer.

Mater is resolute in his independence but he is also very much involved in his community, both as a practicing doctor and as an artist. Indeed, his life at the hospital seems to fuel his art and in turn his art feeds into his medical practice. He sees art and medicine so similarly that sometimes when Mater talks, you can’t be sure to which he is referring.

In his installation, ‘CCTV’, for example, he presents hospital footage as a series of films that show people waiting, milling about in the corridors and praying. “I tried to look at what it means to be human in this media age. New media is changing our idea of humanity but we can still return to it by looking at scenes of suffering or daily ritual. I like to observe how people interact. There’s always a narrative behind my work.”

Sometimes that narrative has to do with the technology of surveillance, like in ‘Boundary’, where Mater created an intricately carved doorway made from cedar wood, fitted with an infrared motion sensor that beeps when you pass through, like an airport metal detector. Other times, it is about systems of knowledge, fusing the insignia of religious belief with the scientific and the medical. You may think the borders between these worlds are clear but juxtaposed in Mater’s work, meaning is ever elusive, and stunning to look at.

In ‘Illuminations’, the ghostly forms of X-rayed torsos return in various guises and poses, phosphorescent and layered with Qur’anic verses, talismans inscribed with prayers and medical notations. Printed on archival paper, the diptychs are skeletons facing one another as if in conversation, framed and embellished in geometric gold leaf designs and arabesques, with calligraphic engravings in Chinese ink. Like ancient Qur’anic manuscripts, the pieces were treated with a mixture of pomegranate, alum powder and tea to preserve them and make them luminous.

“You might think they are dehumanising,” Mater says, referring to prints where often the skulls are blotted out by writing or magical talismanic formulas meant to protect the wearer, “but that’s us. That’s what we all look like on the inside. If you look through the lightbox, you can actually see your insides. It’s beyond physical, it’s metaphysical.”

“I take that and try to give it soul,” he continues, on a roll. “The Illuminations lie between the subjectivity of spirituality and the objective view of what we are made of, they belong to a time when I had difficulty in defining the essence of identity.”

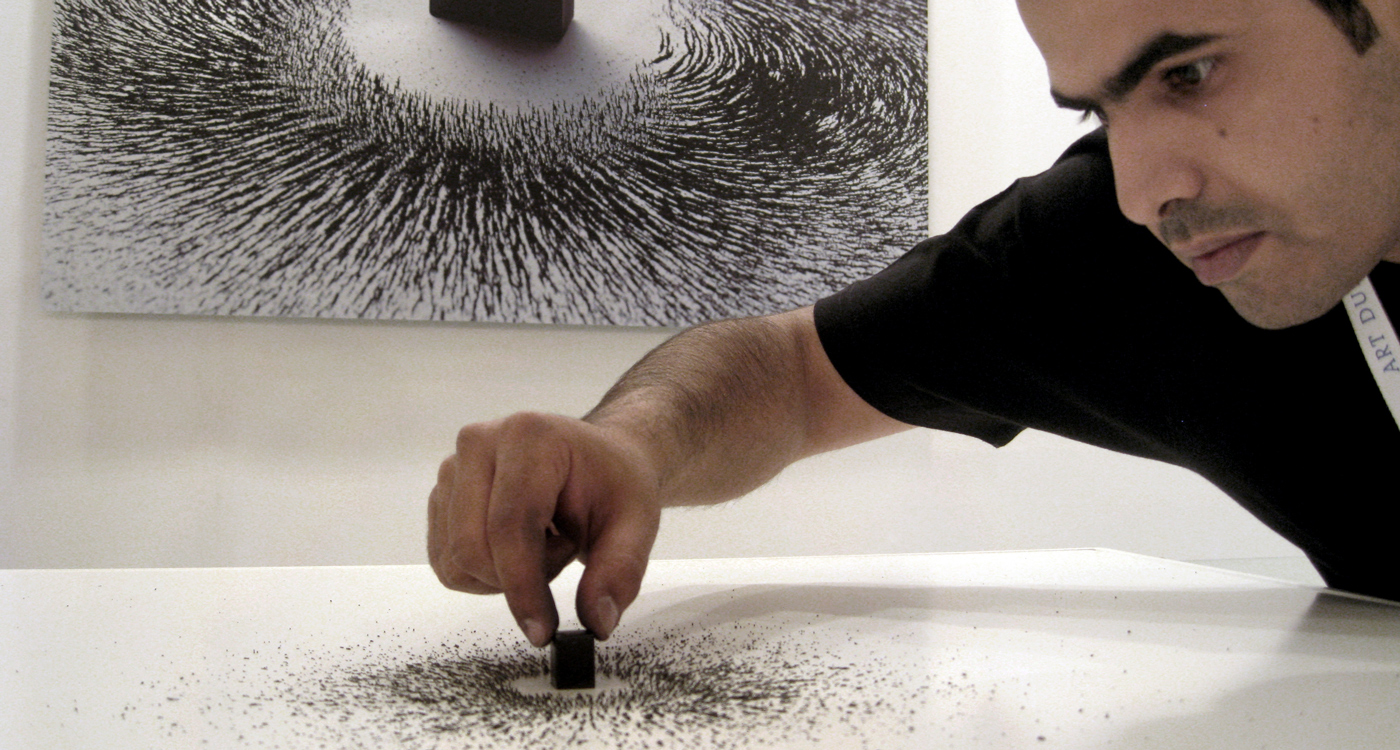

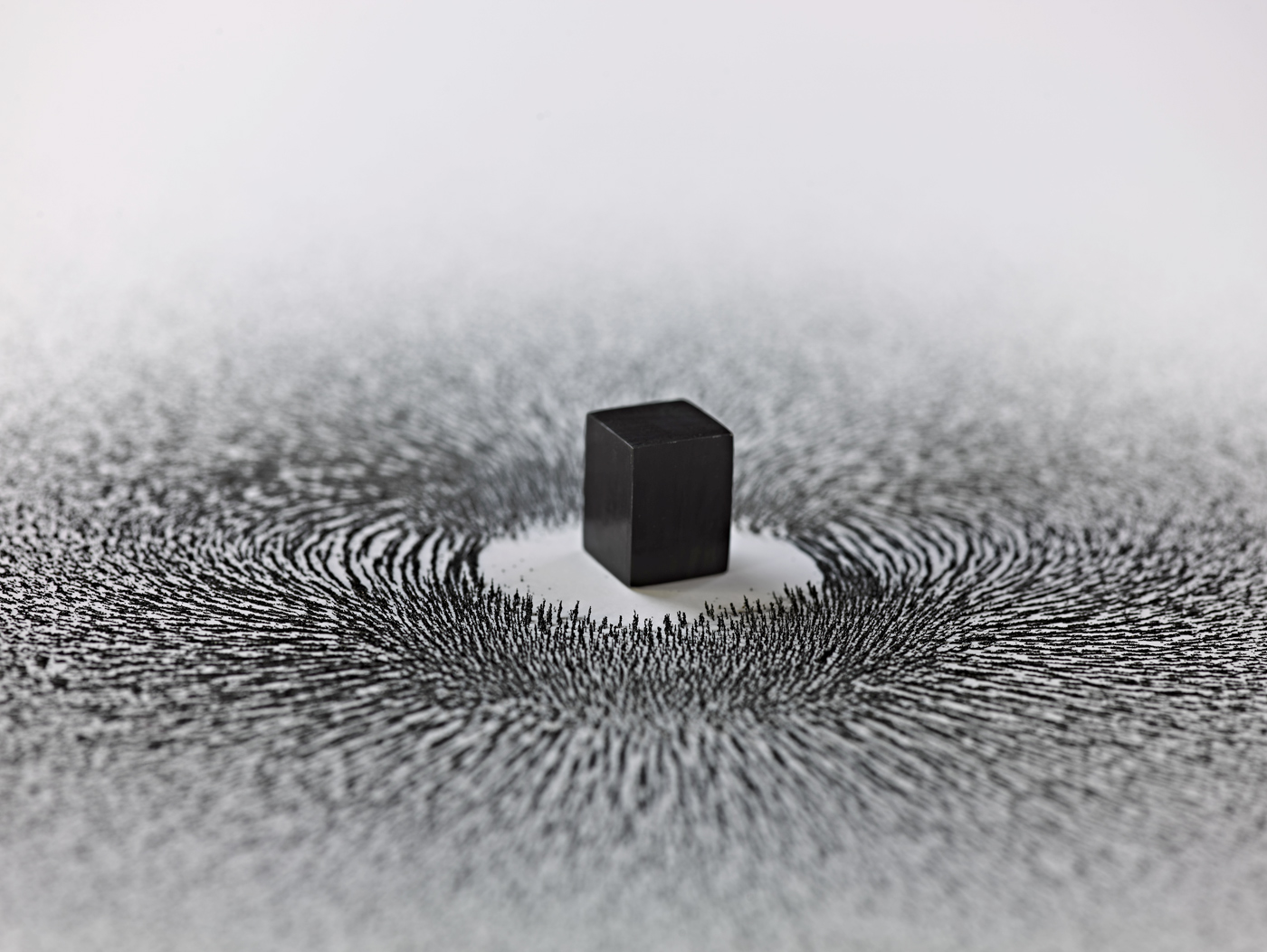

His current obsession is Mecca. He’s portrayed the city twice before, first in ‘Magnetism’, a photogravure of a cubic black magnet on a white background with black iron filings radiating around it in concentric circles – a stunningly simple reference to the Ka’aba and the pilgrims who circumambulate it – and ‘Empty Land’, topographic prints documenting the drastic architectural changes Mecca has undergone. His new project, ‘Artificial Light/ Desert of Pharan’, will involve Mater living in the city for a few years and is an attempt to make sense of its rapid growth, to show Mecca as a real place, with actual urban problems, rather than just as a symbolic place of pilgrimage. “I’m trying to register what is happening,” he says, simply. “That is all.”