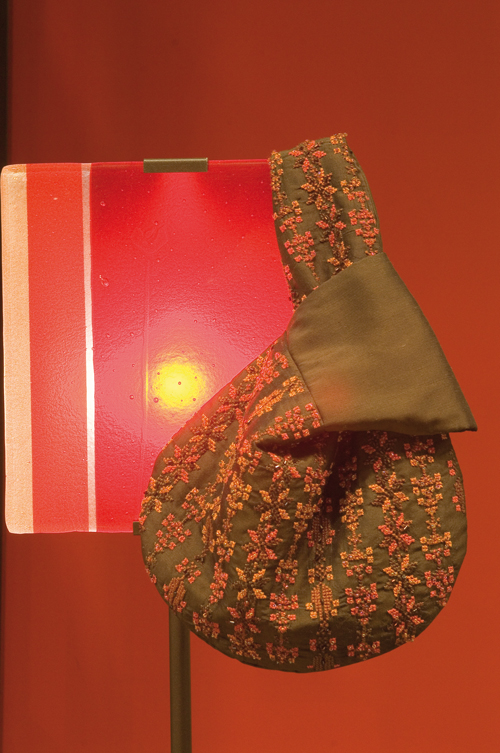

Local artisanal work may bring to mind images of your typical uninspired creations. But in the midst of Beirut’s pulsating city, Carole Corm discovers a strong tradition of fashionable and costly cross-stitches that are all heart. Just tucked off Sidani Street in Beirut’s bustling and noisy Hamra district, Inaash still remains a secret to most – though not to people in the ‘know’ quite obviously. Inaash, the association for Palestinian embroidery in Lebanon has been around for almost forty years. Some of their patterns were showcased last summer at a major retrospective at the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Los Angeles. It also boasts being the preferred artisan shop for many an ambassador’s wife even catching the eye of the wife of Yugoslavia’s fiercely independent communist dictator Josip Broz Tito over thirty years ago. Rumours are abound that many Buckingham Palace royals rest their weary laurels on some of its fine cross-stitch needlework.

photography by Roger Moukarzel

While similar organizations exist across the Levant, Inaash claims technical superiority. “We are the top,” asserts the firm but grandmotherly association president Najla Kanazeh. “We buy the best materials. The canvas is from Germany, the haberdashery materials from France, the silk is from Lebanon’s Abdenour [silk factory] and the very rare Najaf wool comes from, well Najaf [in Iraq].” The soft Najaf wool abayas are particularly captivating.

In a typical 1970s Beirut apartment building where functionality gives way to colonial ornamentation are stored some of the most beautiful pieces of Middle Eastern artisan work. The sheer luxury and elegance of the many embroidered pieces showcased in the glass cabinets is quite astonishing if you consider that typically artisan work is thought of as significantly less than lavish.

Founded in 1969 by Lebanese women from some of the country’s most prominent families – with a bent for leftist politics which probably inspired them to help alleviate some social problems – Inaash was created to temper the harsh situation in Lebanon’s Palestinian camps. In 1973, following a clash between the Lebanese Army and Palestinian factions, most of the Lebanese women involved in the association were pressured to relinquish their support. To give life to the almost defunct Association, Palestinian women came in to fill in the ranks. Amongst them was Serene Husseini, mother to the current Palestinian Authority’s Ambassador to the EU, Leila Shahid. The money from sales still goes to the Palestinians embroiderers as well as into building schools and kindergartens in several Palestinian camps.

Founded in 1969 by Lebanese women from some of the country’s most prominent families – with a bent for leftist politics which probably inspired them to help alleviate some social problems – Inaash was created to temper the harsh situation in Lebanon’s Palestinian camps. In 1973, following a clash between the Lebanese Army and Palestinian factions, most of the Lebanese women involved in the association were pressured to relinquish their support. To give life to the almost defunct Association, Palestinian women came in to fill in the ranks. Amongst them was Serene Husseini, mother to the current Palestinian Authority’s Ambassador to the EU, Leila Shahid. The money from sales still goes to the Palestinians embroiderers as well as into building schools and kindergartens in several Palestinian camps.

There was also another reason for setting up the association. One to do with safeguarding pride in the Palestinian culture or literally ‘reviving’ it. “Inaash is doing fantastic work in keeping the tradition alive, and adapting it to modern life and to keep it growing. There are several other workshops doing the same function in Syria and Jordan, in addition to several workshops in Palestine, in Ramallah, Bethlehem and Jerusalem but Inaash is one of the oldest and best, established and run by women for women,” says Hannan Munayyer, an avid collector of Palestinian embroidery, who owns more than 1,500 pieces.

Historically, the importance of Palestinian cross-stitch embroidery derives from the fact that they helped distinguish where people came from (most notably women). Each village or town would embroider the abayas with a special pattern that would let other people know whether they came from Jaffa, Bethlehem or Jerusalem for instance. As Munayyer puts it, “The characteristics of the Palestinian garb are its exquisite embroidery all over the dress, in cross-stitch or couching stitch, in very harmonious colours. The styles vary from region to region and represented the badge of identity of a particular village or town. Some of the patterns are unique to Palestinian embroidery, and date back many centuries.” Today, the embroidery carries a more aesthetic purpose as well as being a way to safeguard a key aspect of Palestinian heritage. At its most basic, the rich colours used in Palestinian embroidery represent those of the Palestinian flag: a strong red, a plush green mingled with a steadfast black and the purity of white. Other colours were, more recently, weaved into the patterns.

“Over the years, we have also built an encyclopaedia of patterns” explains Inaash’s quality controller. This encyclopaedia is vital, to be able to reproduce century old patterns that have been all but forgotten. As the person who coordinates the work with the many embroiderers living in the camps, “We give them one model which they pass around and then copy,” the controller adds. In total, Inaash employs about 240 embroiderers from the Bekaa Valley to Northern Lebanon. There was a time, though when the Association employed close to a thousand craftswomen. During its golden years in the seventies, Inaash had to establish a rule – similar to the one sometimes applied today by Louis Vuitton – forbidding customers to buy more than one item each.

The pieces are also pretty much of a bargain any way you look at it. An embroidered large shawl made from Najaf wool will go for about 350 USD. The same material and embroidery work on an abaya will fetch about 750 USD, a silk turquoise embroidered pillow case goes for about 60 USD, while an embroidered silk phone holder costs around 25 USD.

From the Jumbo pillowcases that take three months to complete, to the extensively chic and exotically Arabian embroidered caftans and to gadget accessories, the Association is currently making huge strides in making folklore more accessible and trendier to a new generation of consumers.