Slowly, the convoy came to a halt. Headlights flickered off. My first thought was that this was a rotten place to replace another flat tyre. It was dark, we’d been driving all day and there was still a long way to go before we made camp.

Then I saw them. Looming out of the gloom, two female elephants and three calves made their way slowly down the dusty embankment in front of us. Turning on his headlights, Mike Horn, the South African-Swiss round-the-world explorer, slowly began to reverse. It was a gesture of submission, intended to show the elephants we meant them no harm.

I flashed back to our first afternoon together, two days before. Sat in the mist on board Mike’s yacht Pangaea, just off the small fishing town of Walvis Bay on Namibia’s Skeleton Coast, we listened to the basics of elephant and other Namibian wildlife behaviour. Snakes. Scorpions. Lions. Hyena. Spiders. Almost everything out there could, and given the chance, would kill you. Elephants included. My romantic impression of them as noble, gentle and patient giants was demolished as Mike recounted a tale of being charged by an elderly bull a few years before.

I flashed back to our first afternoon together, two days before. Sat in the mist on board Mike’s yacht Pangaea, just off the small fishing town of Walvis Bay on Namibia’s Skeleton Coast, we listened to the basics of elephant and other Namibian wildlife behaviour. Snakes. Scorpions. Lions. Hyena. Spiders. Almost everything out there could, and given the chance, would kill you. Elephants included. My romantic impression of them as noble, gentle and patient giants was demolished as Mike recounted a tale of being charged by an elderly bull a few years before.

“If they start flapping their ears, that means they are angry or agitated and you don’t want that to happen,” he’d told us, as we sat spellbound. “If an adult takes a disliking to you or thinks you are a threat or blocking their way, especially after dark, not even your G-Class is going to keep you safe. They could roll you over like that.” He snapped his fingers. Faces paled.

Now here we were, face-to-face with a family of at least five. In their way. After dark. For a moment, the elephants froze. Ears flapped. The two cows began to sway, unsure of which direction to take. Collectively, we held our breaths. After an eternity, or maybe 30 seconds, one decided to keep walking towards the stand of trees to our left.

Still slowly reversing, we came to halt about 10 or 15 metres away and waited for the bull to appear. He couldn’t be far off. They never left their families unprotected and it wouldn’t do for us to be moving when he appeared. He might take it the wrong way. A few seconds later, a massive male came over the crest of the embankment and trunk swaying, made his way purposefully towards his family. It wasn’t until I noticed that his ears were not flapping, that I exhaled.

Taking a protective position, he stood and watched as we crept past, awed at the sight of a fully-grown African elephant, battle-scarred with one tusk broken, standing just metres away, watching us as we watched him. A kilometre or so later, Mike rolled down his window, beaming.

“You don’t often see elephants that close up,” he shouted through the clouds of dust we’d kicked up. “And never a male that calm. Did you see the way he just watched? He wasn’t even a little agitated. That’s a real privilege.”

These days, many of us fancy ourselves adventurers. It’s not just the reality shows set in remote parts, the shots of amazing places we’ve ‘discovered’ or the status updates of mountains scaled or decathlons run. The exhortation to push oneself to one’s limits is such a ubiquitous modern trope that it verges on cliché. It isn’t until you meet a person to whom the word ‘limit’ doesn’t apply, that you realise how meaningless words like ‘explore’ and ‘challenge’ have become.

Mike Horn is one of those people. Epic adventurer, environmental activist and (probably slightly intimidating) motivational coach, he has trekked around the North Pole and across the South Pole, river-boarded down the Amazon from source to sea, climbed assorted 8,000-plus metre Himalayan peaks without oxygen and circumnavigated the globe more times than you’ve had hot dinners.

As human beings go, he’s impressive. Not just for his achievements but for his warmth, boundless ambition and preternatural energy and for the effortless way he commands attention and the matter-of-fact way he discusses the ways how, if we don’t follow his lead, we will die. He has a booming voice but speaks softly. By nature, he’s a soloist but works frictionlessly with groups. He’s happy to share his stories by the campfire but doesn’t boast and if and when you proffer your own far more modest adventures, he listens attentively and with interest. He’s also tough. Not just in the sense that he has the physique, the skills and the mindset to walk, as he did earlier this year, the length of the Namib, one of the world’s harshest deserts, relying only on what he could scavenge along the way. He’s tough on himself but if the daily goals he sets himself are ambitious, reversals are treated as part of the adventure.

ALMOST EVERYTHING OUT THERE COULD, AND GIVEN THE CHANCE, WOULD KILL YOU. ELEPHANTS INCLUDED.

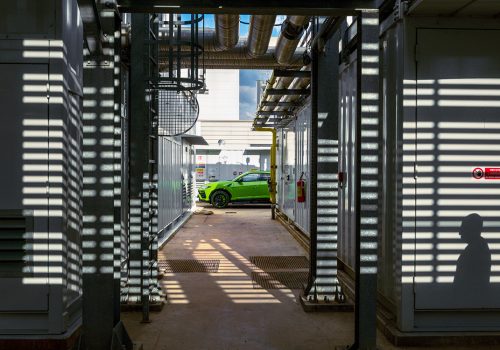

Which is just as well. During our four days of driving through Namibia, fast and for the most part on what can only be described as off the off-roading path, our six hefty Mercedes G-Class SUVs are given such a royal and merciless hammering that in addition to numerous flat tyres – shredded laterally by the stones lining the ‘roads’ – and one broken front grille caused by some exhilarating high-speed manoeuvring over a succession of bumps that lead to what can only be described as a vehicular face-plant, two of the wagons suffer total failure to their front suspension systems on Day three. Given the whipping they receive, the fact that any of them survive is testimony to the tank-like endurance elegantly engineered into them at Mercedes Benz.

While the flat tyres slow us down – in the middle of literally nowhere, staying together means staying alive, so we wait – where we really lose time is when we end up stuck in the sand. The first time is on a misty Skeleton Coast, just as the tide is coming in and a few days later, we get bogged down in a riverbed as we are forced to turn back when it becomes clear our way forwards no longer exists.

Whether these delays can be blamed on the cars or the drivers largely depends on whether you were the one behind the wheel at the time. Either way, digging out takes time and eats deep into our schedule. With hundreds of kilometres to cover each day, none of which should be driven after dark because of wild animals and wilder roads, the setbacks begin to tally up. We keep up the pace for the first two days but on the third, mind gives way to matter and changes to our schedule are made.

This is where Mike’s 26 years of adventuring comes in. He sees tracks where we only see wilderness and he’s able to navigate around most of the obstacles we encounter. He and his team have planned for every eventuality. If our goal is the Epupa Falls on the Angolan border, some 1,106 kilometres north of where we begin it is the journey, not the destination that counts.

And so, as we barrel across desolate, gravel-strewn plateaux, bash along dried-up riverbeds, rumble over rocks, roar along beaches and generally fly, at high speed over stony hill and spiny dale, there is still time to pause, take a photo and soak in the sublime surroundings. We poke around a rusting oil rig on the Skeleton Coast, marvel at plants that can live up to 2,000 years, drive past herds of animals you never see outside of a zoo and, of course, stop to tuck into our picnic lunches – thoughtfully prepared for us by the trio of cooks-cum-camp setters who somehow always seem to be ahead of us on the trail.

In the end, we don’t reach Epupa. The faulty suspensions prove unmanageable and require a last minute change of direction that means we are unable to refuel and without full tanks, there’s no way of reaching Epupa. At first, we think we might be able to refuel in Sesfontaine and reach the falls late in the evening but we get delayed when the three cars bringing up the rear take a wrong turn and get stuck in dunes. By the time we all catch up, we’ve lost the two hours that would have enabled us to get to our goal and so, we end up staying in Sesfontaine.

Shaken and definitely stirred, there are no complaints. We may have fallen short but the trip has been sheer magic. Crazy roads, vast landscapes, total isolation. We’ve seen things and been to places we could only have imagined before and spent four illuminating days in the company of one of the world’s greatest living adventurers. Oh, and after three days camping in the wilderness, there’s electricity and hot showers. Sometimes, civilisation does have its charms.