The world of hotels could easily be categorised as BA (Before Aman) and AA (After Aman). With its pioneering strategy of creating stunning hotels in far-flung locations with limited rooms at high rates – discreetly advertised just by word-of-mouth – Aman resorts have forever changed Hoteldom.

Last night I dreamt I went to Aman heaven again. It might have been Amanbagh in Rajasthan to sit under a Moghul domed cupola. Or Aman Sveti Stefan in Montenegro, a 15th century fortified village with 21st century service. Or Amangiri in Utah, with its Mesa View Suites, which may cost 2,000 USD a night but what’s not to love about an architectural marvel reached through Monument Valley, in the shadow of John Wayne? Aman resorts is that rare hotel group whose name perfectly sums up its ethos.

Aman is Sanskrit for peace: Amanbagh means peaceful garden, Amangiri is peaceful mountain, and the original Amanpuri in Phuket is place of peace. Having been to 10 of the 29 Amans spread across the globe today, I am now a converted peacenik. There are many Shangri-La’s that are the antithesis of Shangri-La – and Banyan Trees are very rarely under one. But Aman and peace are synonymous.

TOP: One of the 40 timber-shingled guest pavilions tucked along the beautifully raw coastline of Amanyara in the Turks & Caicos. BELOW LEFT: With 84 rooms spread over the top six floors of 38-storey Otemachi Tower, the Aman Tokyo is the group’s largest hotel to date, and also the first to be set in a city. BELOW MIDDLE: Aman Sveti Stefan is set on a 15th century Montenegrin island, complete with medieval stone houses, narrow lanes, churches and the former summer residence of Queen Maria of Yugoslavia. BELOW RIGHT: Amangiri is a 4.5-hour drive from Las Vegas in Southern Utah, close to the border with Arizona, where deep canyons and towering plateaus create a raw landscape of immense power.

It all started when in 1985 Adrian Zecha, the Indonesian-born founder of Aman, was looking for a holiday house on the Thai island of Phuket. Wandering along Pansea Beach, he discovered a coconut plantation with a view – and had a light-bulb moment that changed hoteldom. Realising that a small resort would offset his investment in the plantation, he created Amanpuri on the “If I build it, they will come” principle.

And they did come, many by private jet: Charles Saatchi to play Scrabble, Kenzo Takada to find inspiration. Prince Andrew and Sir David Tang would come to work and play. The whole giddy panoply of Hong Kong taipans descended upon the place to hold confidential meetings pre-handover. Kate Moss got married here and apparently, Michael J Fox’s dog liked Amanpuri so much that it was left behind rather than be subjected to separation anxiety.

Venice’s 24-room Aman Canal Grande is housed in a 16th century palazzo whose extensive refurbishment included restoring hundreds of original frescoes, murals, sculptures and chandeliers to their former splendour.

When Zecha and the designer Ed Tuttle created Amanpuri, not only was a new hotel concept born, but a new race of travellers: Amanjunkies, who wanted a piece of the peace. Until Aman, most resort hotels were clunking structures with bedrooms off linear corridors. Zecha’s climb up a curving headland to see the sea that one perfect day in Thailand effectively blew these old-style leviathans out of the water. “The market didn’t know it wanted something new until it saw it,” Zecha says. “Our goal was simply to build something that we would each like to live in.”

BA – Before Aman – the great and the good went to the grand hotels of the Far East: The Oriental in Bangkok, the Mandarin Oriental in Hong Kong, Raffles in Singapore. Or they journeyed to grand European hotels that were as stately as a galleon, faux–Downtons that operated as comfort zones for the aristocracy and monied middle classes who wanted hotels to replicate their homes. AA – After Aman – laid–back private hideaways became the ultimate in casual chic. With a wealth of new money in the 1980s came new customers who wore shorts and flip–flops (it was the staff who wore the suits) and who wanted their houses to mimic the hotels.

In addition to “creating something compatible with the contemporary lifestyle”, Zecha and Tuttle – an American based in Paris – (and later another architect, Jean-Michel Gathy, a Belgian based in Malaysia) were obsessed with design that reflected the surrounding culture. Olivia Richli – who spent five years at Amanjiwo in Java when her husband François was general manager, and later became general manager of the Aman Canal Grande in Venice (where George Clooney tied the knot with Amal Alamuddin) – recalls that she constantly came across details Tuttle had taken from local temples. “There was always the surprise, the tiny interpretation of sense of place. Adrian’s vision is to go to the places not so well trodden, use their vernacular architecture, and employ from the local community. For example, at Jiwo, 95 per cent of our staff came from the villages and we employed a full–time English teacher for them.”

As Zecha’s idea took hold, and as the boutique-hotel ball rolled on – its journey traced by Herbert Ypma in his Hip Hotels books – there were other men at work, primarily Ian Schrager, who followed Morgans in New York with The Royalton, where the doormen dressed better than the guests, and Andre Balazs, with his Standards in Los Angeles, which were not up to everyone’s standards. But – like Schrager’s Hudson on Central Park South, primarily a nightclub with a lobby attached, and his Sanderson in London, a long white marble bar with some rooms above it – these were all urban properties rather than havens of peace. The distinction of the Amans was that each was in a pristine location and unique – a concept that put cookie-cutter chains in the trash can of hotel history. “I follow the backpackers,” Zecha once told me. “They are the adventurous ones; they find the unusual places. I just tag along behind.”

The Amanpuri in Phuket was the first property in Aman’s incomparably luxurious empire and encompassed Thai pavilions aplenty, a vast black-tiled swimming pool with a gasp-inducing view of the Andaman Sea, a superb spa and a beautiful beach accessed via a monolithic stone staircase.

This, of course, isn’t quite true. When he opened his second Aman, in Bali (a location chosen, he claimed, because it has a different rainy season to Phuket, and he hates rain), it was already an alluring destination for informed sophisticates weary of the West Indies – so it wasn’t so much happenstance as careful calculation. Zecha was hardly just an inspired amateur either; he had helped the Marriott hotel chain broker land deals in Asia and, in 1970 – with Robert Burns and Georg Rafael, two other below-the-radar hotel visionaries – had created Regent International Hotel, an Asian luxury accommodation group. When The Regent opened in Hong Kong, all sinister-chic in black glass, it was a sensation. Burns went on to invest in the Four Seasons New York, designed by I.M.Pei, the like of which will never be built again, and Villa Feltrinelli on Lake Garda which, outside of Aman, is the finest small hotel in the world. What Zecha grasped is, first, that size matters; few of the resorts have more than 50 rooms, all of which have fabulous space (in Amanjena, Marrakech, one’s private swimming pool is indoor-outdoor, from the drawing room to the garden). Second, he knew the importance of telepathic service. In Aman world, there are at least four staff per guest, but you never see them. It is no coincidence that the original Amans were in the Far East and India, where labour is abundant and inexpensive, the attitude gentle and soft–footed. Arriving by small aeroplane at Amanpulo, on its own private island in the Philippines, each guest is greeted by name and taken by buggy to their villa hidden in the dunes. It took me three days to work out how the staff knew who was who (the answer: the manager of the Aman lounge at the domestic terminal in Manila – an oasis of calm with showers and Floris soap – sends descriptions of the guests’ clothes ahead to the resort).

You could, if your beach novel were rubbish, play Grandmother’s Footsteps with the staff. I never caught a single staff member in my room, yet it was always sparkling fresh – not a crease on the bed (getting the bed made before lunch is a challenge in some of the best Caribbean hotels), not an unfolded towel. How did I know the room fairies had been? Because the postcards, of which I write lots to the 14 godchildren, had been replaced on the desk – and with different images. In any Aman, your cards will be posted free of charge: a small thing, but a little touch of class. At Amanpuri, the white sand is sprayed with water to make it cool for the guests. At Amanyara in Turks & Caicos, you’re afforded free international calls. In Sri Lanka, at Amangalla and Amanwella, different skin lotions are put into the bathrooms, depending on the weather. You never sign for anything: for the glass of fresh juice or the icy white wine (funny how one always has wet/sandy hands from the pool/sea when the annoying bit of paper is thrust at you in lesser establishments).

Although these are Aman standards, “there are no rules, no handbook,” says Olivia Richli. “Each general manager runs the property as if it is his or her own, welcoming the guests into a home where the staff are part of the family.” Jonathan Blitz, formerly general manager at Aman-i-Khás, the tented camp in Rajasthan, and afterwards Amanwella, feels that the Aman magic is “remembering guests’ names, making them feel important and loved, at peace. Amans are not homogenised, and the underlying principle is to be honest, genuine and good.”

Evoking the palatial elegance of the Moghul era and set in Rajasthan, India’s dramatic frontier region, Amanbagh is a verdant oasis of mature palm, fruit and eucalyptus trees lying within a walled compound that was once the staging area for royal hunts.

And that’s exactly how they make you feel. I remember sitting on a beautiful leather trunk at the end of my bed in Aman-i-Khás, struggling to put on my anti-mosquito socks, and hearing rattling inside the trunk. Opening it, I found it full of ice cubes, chilled beers, soft drinks, bottles of water – fortifications for the intrepid in search of tigers. Twelve years ago, at Amanbagh, in the Aravalli Hills outside Jaipur, I arrived in tears because I had seen a dog being kicked and beaten by the side of the road. I had wanted to stop the car and rescue it, but had been feeble. Zecha, who was at Amanbagh for his 70th birthday, immediately said: “What, didn’t you bring it, you silly girl? Look!” And he waved his arm towards the vast, green lawn, where puppies rolled in the grass.

It is not all lovely in the garden, though. Aman food has long been a bit dodgy. Bruce Palling, food columnist for The Wall Street Journal and a friend of Zecha, says: “Adrian reckoned that the Amanjunkies had eaten, or could eat, at the world’s best restaurants. So he wanted simple food, locally sourced. It fitted in with his idea of less is more, no TV, no bar in the resorts, but elegance and style in a third-world environment.”

There are televisions now, and Wi-Fi and iPod docking stations; the American Amans certainly could not exist without them – although each is in an extraordinary location. Staying at Amangiri in Utah is one of the great modern adventures; I could even be persuaded to hike there because the landscape is so archaeologically wondrous (although a Navajo healing treatment in the spa would be my first choice of activity).

Spas, too, were long a problem for Aman; at Amanjiwo, there is still just one treatment room – in a converted bedroom. But the hotels are evolving. A full spa has now been put into Amanpuri (it returned the almost 2 million USD investment within a year) and the Amangiri spa is state-of-the-art. “Lifestyle does not stay static,” Zecha once told me. “We continue to keep our finger on the pulse of how things are evolving, to offer a lifestyle experience without limitations.”

At Amanfayun in Hangzhou, whose design is based on a Chinese village, there are four different restaurants, upping the food game considerably. In the Amans in Bhutan, they even grow their own produce; the one in Timpu, based on a traditional monastery, is outstanding architecturally, and the Aman Summer Palace in Beijing has sweated blood to embrace its heritage, even though you can’t see anything (as the writer Peter Hughes says: “Amans spend a fortune on making rooms extraordinarily dark, then another fortune lighting them in a super-complicated way”).

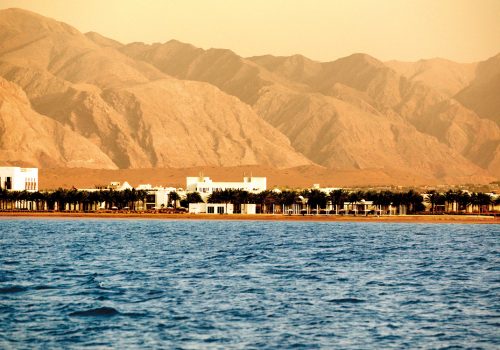

The big question is what happens AAZ – After Adrian Zecha? He is 82 now, and while the company may still be expanding, with a stellar collection of 29 properties including recent additions like the AmanZoe in Greece, Amanruya in Bodrum, Amano’i in Vietnam, China’s third Aman – the Amandayan, as well as the world’s first city-based Aman in Tokyo, it is also facing bitter in-fighting between its new shareholders and has seen Zecha step down, then reinstated, then leave once again as the company’s chief executive just in the last year.

Whatever the outcome, the business itself is still an enticing one, in part because it hasn’t fulfilled its potential – producing estimated annual revenues of 250 million USD, of which 45 million USD are profits, but with occupancy rates of just 30 per cent, compared with an industry average of 76 per cent for elite hotels. Unfortunately the ramifications of exploiting such a potential could have the adverse effect of making the group less exclusive and therefore, less Aman. We just hope the new strategy keeps respecting that an Amanjunkie is a blessed state of being. As Olivia Richli says: “We don’t want anyone leaving unhappy.” Aman to all that.