Looking to invest in real estate? How about a prime piece of land surrounded by mountains and trees in sunny Palestine? Even better, how about a newly constructed, upscale pied-à-terre, just steps away from the country’s only outdoor shopping mall where you’ll find all your family’s favourite brands, including American Eagle Outfitters, Boss and Mango? It’s called Rawabi City, and yes, a foothold on one of the world’s most prized landmasses can be yours today.

Looking to invest in real estate? How about a prime piece of land surrounded by mountains and trees in sunny Palestine? Even better, how about a newly constructed, upscale pied-à-terre, just steps away from the country’s only outdoor shopping mall where you’ll find all your family’s favourite brands, including American Eagle Outfitters, Boss and Mango? It’s called Rawabi City, and yes, a foothold on one of the world’s most prized landmasses can be yours today.

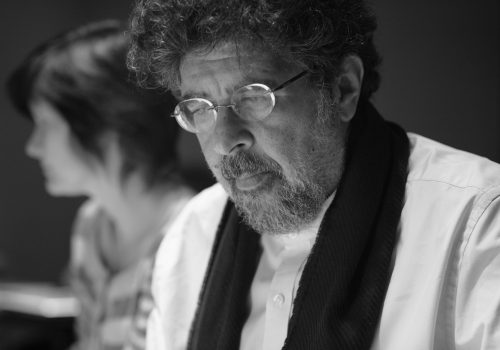

Palestine’s 1.4 billion USD beacon of light is an unlikely haven that’s shaking things up in a political climate that’s heavy on uncertainty and wrought with international wrangling over divestment from IsraeI. It’s the brainchild of Bashar Masri, a Palestinian-American businessman with utopian aspirations and the ideal pedigree. And despite the obvious pitfalls, Masri is forging ahead with his strategy.

“When we get our free state I want to be strong, I don’t want to end up like another Sudan,” explains Masri, an entrepreneur who also describes himself as Palestine’s biggest employer. As the founder and chairman of Massar International, Masri overseas 35 companies that span everything from insurance and agriculture to IT. “I think we’re lucky as Palestinians because there’s an opportunity in history to build the ideal, model nation and I think I’m part of those lucky people and I’m doing my part.”

Following a massive residential project in Morocco in 2004, Masri initiated a master plan for a new, high tech Palestinian city that would include a proper city centre, an outdoor park, 6,000 living units and the kind of facilities found in other modern towns around the world.

The ambitious West Bank project is located just 20 minutes away from Ramallah, set on 6,300 square metres of land, with funding coming primarily from the Government of Qatar. Already, 90 per cent of the city’s main infrastructure and 1,250 apartments have been completed. Besides the fundamentals like the sewage system, access roads and water supply, there is also an outdoor, roman-style theatre that accommodates an unprecedented 20,000 people, an adventure park featuring the region’s longest zipline, bungee jumping, ATV’s, picnic facilities and even public art installations, including one welcoming visitors to Rawabi’s Visitor Centre. And that, according to Masri, is the key to the city’s success.

I THINK WE’RE LUCKY AS PALESTINIANS BECAUSE THERE’S AN OPPORTUNITY IN HISTORY TO BUILD THE IDEAL, MODEL NATION.

“When building a city, the most important thing is density,” claims Masri. “There’s an Arabic saying that says ‘Heaven without people is not worth visiting’. So we focused on Rawabi becoming a destination.” It’s a plan that seems to be working. Around 800,000 people have visited Rawabi at least once over the last year, concerts at the amphitheatre have sold out (at the time of this interview, Masri was in Beirut in an effort to secure a performance by Egyptian singer Tamer Hosny) and Palestinian families have been flocking to Rawabi to take advantage of its manicured gardens and scenic shish kebab facilities.

Still, even though most of the apartment units have been bought, only 30 to 40 per cent of owners are actually occupying their properties. The reason? Nearby Israeli checkpoints mean that getting to Ramallah, where many of the Palestinian who can afford Rawabi work, can be brutally arduous. “This is not some traffic jam, it’s a checkpoint where soldiers may get you out and harass you, somebody might attack the soldiers while you’re being searched, and you could be the person in the middle,” Masri points out. The commute often takes up to three hours.

Still, even though most of the apartment units have been bought, only 30 to 40 per cent of owners are actually occupying their properties. The reason? Nearby Israeli checkpoints mean that getting to Ramallah, where many of the Palestinian who can afford Rawabi work, can be brutally arduous. “This is not some traffic jam, it’s a checkpoint where soldiers may get you out and harass you, somebody might attack the soldiers while you’re being searched, and you could be the person in the middle,” Masri points out. The commute often takes up to three hours.

But that’s only one of the challenges of nation building in an occupied state. Israel’s chokehold on Palestine also mean that the Rawabi’s developer has had to plan for the possibility that supplies might be detained by Israel, thereby delaying the project. “What we did is build massive stockpile facilities, and stored construction material worth 70 to 80 million USD. We don’t do that in normal projects. Obviously, that’s costly for financing and it can get damaged, but it’s an insurance policy,” reveals Masri.

And then there are the critics. Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS), the Palestinian-led movement for freedom that’s been leading the push to boycott Israel – a growing campaign that has caught the attention of several large corporations, including HSBC, Europe’s largest bank, which recently pulled out of a major Israeli defence contract citing human rights violations, and that also recently sparked several US-states to approve anti-boycott legislation – have been very vocal in their disapproval of Rawabi’s commercial relationship with Israel. But Masri points out that Palestine and its occupier are normalising regardless: 150,000 Palestinians already work in Israel. Instead of a blanket boycott, he proposes a more targeted response.

“The tactic should be about the settlements. By equating the settlements with Israel, I’m afraid they’ve diluted the battle. If we all focused the boycott only on settlement, no state would have made a law against BDS. We would have won a battle. But we never plan properly,” he remarks.

“The tactic should be about the settlements. By equating the settlements with Israel, I’m afraid they’ve diluted the battle. If we all focused the boycott only on settlement, no state would have made a law against BDS. We would have won a battle. But we never plan properly,” he remarks.

To that effect, Masri says his companies make it a point not to buy anything that comes from the settlements – and include this as a clause in all their contracts. “We have a team that follows this because unfortunately a lot of merchants try to squeeze their products in, because they’re subsidised and therefore cheaper.”

He’s also quick to point out that BDS has not done much to strengthen Palestine’s position, and suggest it should focus on encouraging the state to become more independent from Israel, by producing its own electricity, for instance.

“I asked BDS, ‘Why aren’t you boycotting Israeli electricity?’ They said because there are no alternatives. So I said, ‘It’s called alternative energy.’ And guess what? It’s environmentally friendly,” he adds.

And sure enough, during our interview in a café in Beirut’s tony Saifi Village, Masri reveals that he has just secured a contract for a big solar panel project in Palestine that could eventually produce 90 MW of electricity. And though this project has potential financial gain (as opposed to Rawabi, which he says is more about nation building) it also serves his broader purpose. “It’s the kind of project where you make money and sleep comfortably. In Palestine, it’s doubly good – it’s better for the environment and reduces dependency on Israel.”

Convinced? An address in Rawabi can be yours for around 800 USD per square metre. But that might change: Masri says they cannot keep up with demand and that has been driving up the price. He also maintains that although Rawabi is meant to be a high-end community, the aim is for working Palestinians to be able to afford living here. “Building a state requires a middle class,” he points out, adding that none of his employees make less than 600 USD per month, well above the minimum wage of 400 USD per month. He concedes though that this doesn’t equate to a middle class income and points out that he is actively trying to be a part of a growing economy. “In Rawabi I have at least 250 IT programmers. Their average salary is 2,000 USD per month.” And for those not lucky enough to be working for one of Massar International’s entities, Masri points out that he has worked with local banks to help prospective homeowners secure mortgage loans at reasonable rates, around 5 to 6 per cent.

Is he an idealist? Admittedly so. But Masri doesn’t have his head in the sand. He’s nervous about recent events and uncertain about what might come next. It’s just that he sees beyond that, to a certain, inevitable restitution for Palestine.