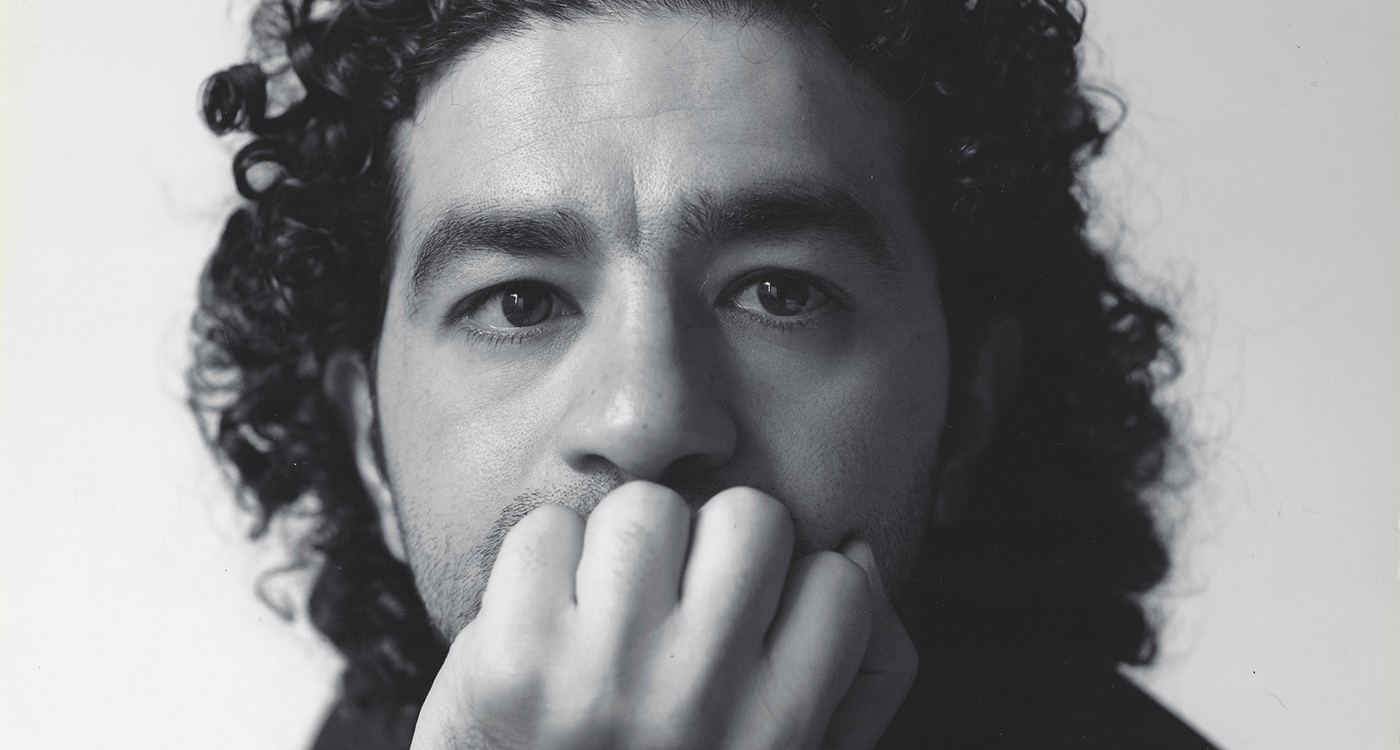

One day in 2004, the Iraqi-Dutch filmmaker Mohamed Jabarah Al Daradji was filming scenes for his first feature film, ‘Ahlaam’, on Haifa Street in Baghdad when he and his crew were abducted by an Iraqi militia affiliated with Al Qaeda. “They accused us of working with the Americans,” Al Daradji says. While being interrogated, he and his team were rescued, they thought, by the Iraqi police, but then the police handed them over to the Americans. “We were imprisoned in the Green Zone for five days,” Al Daradji says. The Americans thought the crew was filming Al Qaeda training videos.

One day in 2004, the Iraqi-Dutch filmmaker Mohamed Jabarah Al Daradji was filming scenes for his first feature film, ‘Ahlaam’, on Haifa Street in Baghdad when he and his crew were abducted by an Iraqi militia affiliated with Al Qaeda. “They accused us of working with the Americans,” Al Daradji says. While being interrogated, he and his team were rescued, they thought, by the Iraqi police, but then the police handed them over to the Americans. “We were imprisoned in the Green Zone for five days,” Al Daradji says. The Americans thought the crew was filming Al Qaeda training videos.

“It took a year or two for me to get over it,” Al Daradji says on the phone from Baghdad, where he lives and works. “I made a film about it, which helped me to handle the anger and frustration I felt. Film is my reaction to trauma.”

Obviously what happened to Al Daradji is appalling, but both sides might be forgiven for doubting he was a filmmaker, given that the Iraqi industry had been largely dormant since Saddam Hussein’s ascent to power in 1979. Al Daradji’s film ‘The Journey’, which was released in September 2017, was the first film by an Iraqi director to screen in Iraqi cinemas in 27 years. It premiered that same year at the prestigious Toronto International Film Festival, was selected at the Busan and Doha festivals, won an award at the Muscat festival and even gained the official selection of Iraq for submission to the 2019 Academy Awards for the Best Foreign Film category.

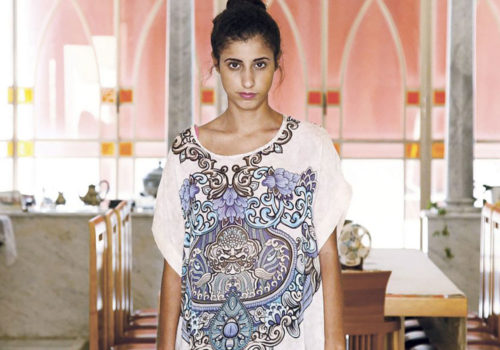

The film follows a day in the life of a female suicide bomber (Zahraa Ghandour, in her debut screen performance), and the diverse group of Baghdad residents who circle in and out of her orbit, including a man she takes hostage. The backdrop is a Baghdad train station on the day Saddam Hussein was executed by American occupation forces in 2006. The Hollywood Reporter reviewed the film as a kind of local allegory that is “part will-she-or-won’t-she thriller and part parade of symbolic characters who represent the country’s wounded population.”

Al Daradji was inspired to make ‘The Journey’ from a story he read in the newspaper, in 2008, about a female suicide bomber who turned herself into the police five minutes before her bomb was set to go off, only for the police to strip her and tie her to the railings outside the station, in order to humiliate her. It led Al Daradji on a two-year-long struggle with Iraqi bureaucracy to receive permission to interview female members of Al Qaeda and other extremist militias.

When they finally accepted, Al Daradji was struck by one of the women he met in prison. “There was this beautiful Iraqi girl with big eyes, and so smart. We talked for two hours and I thought ‘she could be my sister, or my girlfriend’. I was reminded that these people are human after all, and they are also victims in their own right.”

The director had a similarly strong reaction when first meeting Ghandour, the television presenter who became his leading lady. Their initial encounter “was by pure coincidence,” Al Daradji puts it. “She came to the film centre in Baghdad where I was editing. She opened the door to ask a question, and I looked in her eyes and saw her face and knew this was the girl.” Once Ghandour accepted the part, Al Daradji put her through two years of intense preparation to turn her into someone who could play a suicide bomber. “I made her into a special forces soldier,” Al Daradji laughs. “We actually did physical exercises where I weighed her down and made her run along the Tigris River.”

Al Daradji says fell in love with film as a young boy, citing Youssef Chahine’s 1969 film ‘Al Ard’ as one of his key inspirations (as well as the Francis Ford Coppola classic ‘The Godfather’). Chahine’s film depicts the relationships between peasants and their landlord in rural 1930s Egypt, and explores ideas of collective response to oppression (as does ‘The Godfather’, sort of). “I saw it and felt I wanted to do something like that,” says the 40-year-old Al Daradji.

“I one hundred per cent believe that film can help us Iraqis work through our collective trauma,” the director says. “We don’t have the distance from what has happened to us [starting in 1969 with Saddam Hussein, then the Iran-Iraq War, then the Ba’athist regime, the Gulf War, the Iraq War, Al Qaeda, the American occupation, ISIS, and so on to the present day] because our drama continues. But film can help us a lot,” he says, to get perspective on “our tragedy.”

Having fled as a refugee to Holland at the age of 17 and been granted Dutch citizenship, Al Daradji returned to Baghdad in 2014 to take up residence in the same neighbourhood where he had been a theatre student nearly two decades earlier. “Some people in Iraq ask me, ‘why are you here?’ I tell them ‘I love my country.’ I wanted to contribute to rebuilding Iraq after 2003.” The only way forward, he believes, is through “art, culture, and education. These will feed us.”