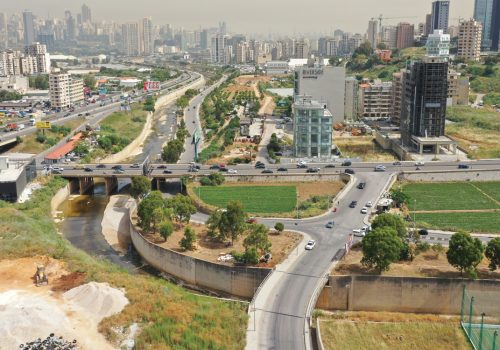

When you arrive at the sleek, white 250,000 square-metre glass building, you’ll be hard-pressed to guess it’s a shoe factory. Perhaps the architecture is too contemporary. Or maybe the airy interior, with tastefully appointed artworks in every corner, has the feel of a gallery. But if you take a closer look, it’s the art that gives the place away.

Smack in the middle of the entrance is an orange globe, its continents formed from pencils. Their rubbers represent the Gommino pebbles that made Tod’s and its soles, so instantly recognisable. They’re a Diego Della Valle innovation, introduced back in the 1970s, when luxury shoes only came soled in leather because rubber was ‘cheap’.

But when Fiat’s head, the legendarily sartorial Gianni Agnelli, was spotted sporting Della Valle’s new driving moccasins in 1979, their success was ensured. A defining moment in the company’s history, those 133-pebble soles became Tod’s trademark. Driving this point home is a gigantic, floor-to-ceiling blow-up of one of them in the lobby. It faces another gigantic footprint photo, shot by Vogue’s Giovanni Castel.

As I embark on the factory tour, Della Valle is on his way back from a football game in Florence played by his own club, ACF Fiorentina, which he saved from bankruptcy in 2002.

The 60-year-old Della Valle is widely regarded as an embodiment of Italy’s Dolce Vita but is more importantly the driving force behind Tod’s hugely successful expansion from a leather manufacturer into a global luxury group with annual revenues of more than $1.2 billion.

He’s a busy man. In addition, Della Valle runs three other labels, Hogan, which is known for its sports line, Fay, a ready-to-wear label and Roger Vivier, all under Tod’s Group. He acquired Schiaparelli in 2007, owns a swathe of Saks and a couple of Italian companies, is helping fund the Colosseum’s renovation and is working on a high-speed train to compete with Italy’s national network. With personal assistants in three different cities, I’m told he often doesn’t know his own schedule.

Born to a family of cobblers, Della Valle’s grandfather, Filippo, began manufacturing shoes in the early 1900s and his late father, Dorino, biked to the factory until his last day. “My father certainly has a huge influence on my life,” Diego later reveals. “He was a very important example to follow and he inspired me through his dedication to his work.”

Though his father had encouraged him to study law, Della Valle joined the family business out of passion and today, despite having grown into a luxury conglomerate, Tod’s is still a family business in essence. Della Valle’s brother, Andrea, is VC and his eldest son oversees advertising campaigns. While Della Valle inherited the business, it’s thanks to him that it has grown into the empire it’s become today.

Tod’s hasn’t done too badly with the economic downturn either. Last year, revenues increased almost 8 per cent over 2011 to a whopping 990 million USD. Consequently, while other firms have had to move production to Asia, Tod’s remains staunchly and proudly, Made in Italy. “We’re attentive to innovation, which is important if we are to find new leathers and new techniques,” he tells me, “but the tradition of hand-made and made in Italy is always the point we start from.”

We cross a hallway flooded with light, passing Jacob Hashimoto’s high-ceilinged installation which floats delicately above us: 1,000 kites made of rice paper, a shifting illusion. Looking through the glass to the expanse of green beyond, I think I see another optical illusion but it turns out to be the large sculpture of a woman’s face by Igor Mitoraj, framed by a bush.

We enter a long corridor, passing the paparazzi-style clippings of celebrities wearing Tod’s plastered outside the creative team’s offices which inside, are a colourful chaos of sketches, bags and shoes. This is where next season is dreamt up.

I’m taken to see how those dreams materialise. In a stark, open-plan setting, men and women dressed in white coats develop the sketches, turning them into actual prototypes. They are the technical team but despite that, they initially do everything by hand. Sticky paper is plastered onto a shoe mould to demonstrate how the proportions will look in three-dimensions, then a template is created using computer software, not the other way around. Cardboard cutouts based on the desired composition are then printed to outline the leather sections of the shoe. I’m told that each pair of shoes can have 30 separate parts.

I’m taken to see how those dreams materialise. In a stark, open-plan setting, men and women dressed in white coats develop the sketches, turning them into actual prototypes. They are the technical team but despite that, they initially do everything by hand. Sticky paper is plastered onto a shoe mould to demonstrate how the proportions will look in three-dimensions, then a template is created using computer software, not the other way around. Cardboard cutouts based on the desired composition are then printed to outline the leather sections of the shoe. I’m told that each pair of shoes can have 30 separate parts.

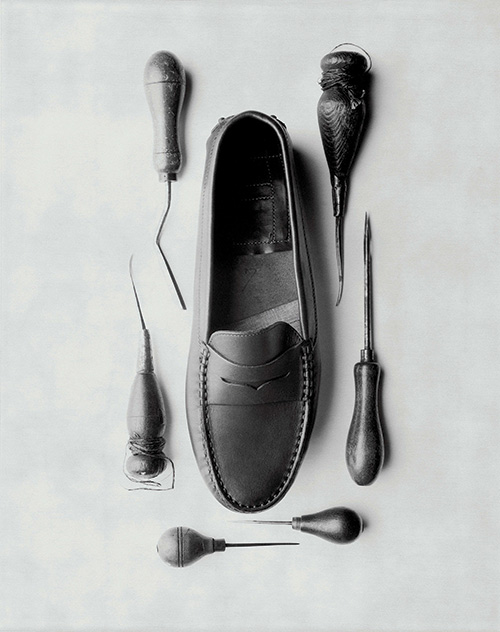

From here, we’re taken to the third, hidden layer of Tod’s world. Filippo’s original workshop table stands outside, indicating the way. Inside, it’s a panorama of thousands of spools of multi-coloured thread, whirring sewing machines and cutters. The smell of leather is pervasive. There’s also a room where wooden lasts (feet-shaped dummies) are made, carved like sculptures.

Checked for imperfections by a team of eight, the leather is overseen by quality inspection expert, Tony Ripani, who has been with Tod’s for 35 years. He shows us how the outer surface of the skins (sourced from all over the world) is usually grainy while the inner surface, which once touched actual flesh, is smoother. Through a magnifying glass, you can even see the pores.

Ripani runs his hands over one sample, feeling for uniform thickness, then abruptly pinches it. “You see how the wrinkles disappear,” he says in Italian, explaining that the leathers are subject to different types of treatment, some of which can degrade them. He pours some water on a piece of suede that’s meant to be resistant. Amazingly, it just rolls off in a hundred tiny silvery droplets. “Leather from baby calves is the most supple,” Ripani continues, as I touch leather so soft, it’s more like velvet.

The precious skins are next: alligator from Australia, anaconda from Argentina, pink ostrich and green and gold-laminated lizard skins. These will soon be transformed into some of Tod’s most coveted shoes and handbags.

Pins in mouths, I witnessed another group piece the different sections together with small nails, hammers and a gun, hand-stitching them before placing them in a pressing machine that will give the shoes their form. An insole is attached inside as a final step.

Head full of images from my 3-hour tour, I’m now ready to meet Mr. Della Valle before he rushes off again to Milan. His light-filled office houses another antique shoemaking table, strewn with tools I couldn’t even name. He walks in and shakes my hand warmly.

His navy blazer and jeans epitomise the informal elegance Tod’s espouses. He has this relaxed, confident air to him and I can see his eyes smile behind his yellow-tinted spectacles as we speak.

Later, I think about what he tells me about taking care of his 900 employees and how the HQ is not just a factory, it’s also a place for imagining.

As I exit the premises, it’s lunchtime. Employees’ children run free on the playground, on its swings and slides. Earlier, as I entered the sunny nursery provided for children between the ages of 2 and 5, an alarm sounded, both when we opened the door and when we left. Clearly, they are safe here. The adults too, get spoiled. There’s a gym and a trainer and the lunch break is two hours long, allowing employees to choose to spend time with their families at the factory or at home.

“I believe that taking care of our employees creates a relationship of respect and trust,” Della Valle tells me, explaining what ought to be the maxim every company lives by but which all too few actually follow. “My employees are good workers, so they’re precious to us.”