When architect Nabil Gholam first saw Villa Z, an old abandoned house damaged by years of civil war and military occupation, it was far from love at first sight. From an architectural perspective, it was no gem, with a façade covered in rough stone coursing and a red tile roof that seemed, well, a little dated. Even worse, the structure had been ravaged by years of civil war and used as a base and detention centre by military groups. There was eeriness to the place, an eeriness that begged to be expelled.

When architect Nabil Gholam first saw Villa Z, an old abandoned house damaged by years of civil war and military occupation, it was far from love at first sight. From an architectural perspective, it was no gem, with a façade covered in rough stone coursing and a red tile roof that seemed, well, a little dated. Even worse, the structure had been ravaged by years of civil war and used as a base and detention centre by military groups. There was eeriness to the place, an eeriness that begged to be expelled.

“It was like a punch in the stomach,” the architect recalls of the moment he first set foot on the expansive property, not long after its last occupiers, the Syrian military, had pulled out of the country following the popular uprising of 2006. What was left behind was a sombre reminder of dark times. There were local tales of prisoners who had been brought here, never to be seen again, and there were signs of them too – etchings made with matchsticks or fingernails on the inner walls of a small water reservoir, spelling out the names of the detained and the dates they had been taken. There were discarded torture instruments too, and bullet holes. “I must tell you it was very disturbing. Maybe I’m a sensitive type, I didn’t think I was. But I was really shaken.”

Given the unexceptional design and disturbing history, it’s not surprising that Gholam was veering towards an architectural tabula rasa that would raze the property to the ground and allow him to start from scratch. After all, if the goal was to erase the bad memories, it seemed like the most logical way to proceed. Except, that’s not what the villa’s proprietor had in mind. This owner, whose grandfather had built the house in 1947 after returning from Africa, wanted the original façades to be kept intact so that they could at least preserve the good history, while removing much of the bad.

The home, which is situated in the beautiful area of Bologna, near Bteghrine and Dhour El Choueir, on the edge of Beirut’s northern mountains, was modern and luxurious for its time, boasting the first private tennis court in the country. It also sat on an impressively large 40,000 square-metre plot of land overlooking Mount Lebanon. To add to its provenance, it turns out the home was also once used by former President Camille Chamoun, when he was momentarily ousted from office in the late 1950s. The owner’s grandfather reputedly offered his villa as a temporary office and refuge until the president was called back to duty in the parliament. And then, there were the memories: the good ones, of childhood summers spent frolicking in its idyllic gardens, as well as the bad ones – the owner’s brother was reportedly killed while defending the home at the onset of the Lebanese civil war.

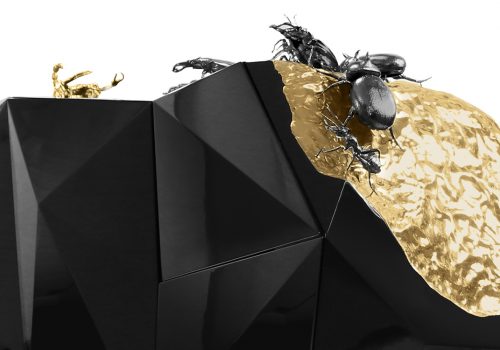

It took about two months for Gholam to come up with a concept for his client, Philippe Jabre, a financier and discerning art collector who lives for the most part in Europe but wanted to use the house as a summer retreat. (It was codenamed Villa Z after Philippe’s wife – Zahia “Zaza” Riachi Jabre.) “It’s very rare that I get involved in restoration projects. It’s something that I find beautiful, but it’s not really my calling,” he says. His firm, Nabil Gholam Architects, has a diverse portfolio that includes mostly large-scale luxury projects and residential towers but given how the project moved him, he devised a plan to attempt to exorcise the demons and usher in a bright new future. The plan would take inspiration from a hermit crab, who seeks shelter in abandoned shells and makes them home until he outgrows them, and the work of Caspar David Friedrich, a 19th century German Romantic landscape artist known for his paintings of heroic ruins invaded by nature. “They were very important for me because they were about reinventing a place that was dead.”

One of the constraints he and the Jabres imposed on themselves was not to kill a single tree, which was especially important considering how tall and old some of the native pine trees were on the property. It would prove to be a genesis for Gholam, one that allowed the beauty of nature to regain the upper hand after years of deforestation by the house’s various occupiers, who would use the wood either as means of keeping warm during cold and snowy winter months (the villa sits at about 1,500 metres above sea level), or as means of generating income. To drive home this point, the owner planted over a thousand trees, which have prospered since the home was completed in 2012.

In the summer, the white stones of the original structure almost disappear behind the leaves of climbing ivy only to reappear in the winter, lined with bare stems that conjure veins. “It’s organic, almost body like. It’s like a vascular system over the old stones,” Gholam says before pointing out the blood red stains on the white flooring left untouched, caused by oxydising exterior perforated Corten sheeting. These panels, which are stacked in box-like structures over sections of the villa, utilise a type of steel that oxidises and alters in its appearance depending on the weather. They protrude at the roofline and allow Gholam to camouflage solar tubes that heat the water for the house and the aforementioned red-tiled roof, which had to remain intact due to local planning by-laws. The perforations in the metal were made in differing sizes to create tree-trunk like silhouettes as the light washes through, done to pay homage to the fallen souls. “These messages are subliminal,” says Gholam, “they’re not visible, unless of course someone points them out.”

In the summer, the white stones of the original structure almost disappear behind the leaves of climbing ivy only to reappear in the winter, lined with bare stems that conjure veins. “It’s organic, almost body like. It’s like a vascular system over the old stones,” Gholam says before pointing out the blood red stains on the white flooring left untouched, caused by oxydising exterior perforated Corten sheeting. These panels, which are stacked in box-like structures over sections of the villa, utilise a type of steel that oxidises and alters in its appearance depending on the weather. They protrude at the roofline and allow Gholam to camouflage solar tubes that heat the water for the house and the aforementioned red-tiled roof, which had to remain intact due to local planning by-laws. The perforations in the metal were made in differing sizes to create tree-trunk like silhouettes as the light washes through, done to pay homage to the fallen souls. “These messages are subliminal,” says Gholam, “they’re not visible, unless of course someone points them out.”

Corten was also used to wrap the inner window frames, creating a physical barrier between the original walls and the inside of the home. The notion was that these windows, which offer sweeping views over Lebanon’s lush, green mountainside, had been left as they were, so it was important to offer a fresh perspective. “The colonel of the secret services who ordered arrests and brought prisoners here saw the same views as the owner’s children see now. The act of reviving the house has added, in a way, another link in that long chain. And that is what the owner wanted.”

Today, the villa’s transformation is mostly complete, except for the sleek chapel Gholam plans to build on the side of a small cliff. The project began with a gutting of the interior and the addition of underground space beneath the courts, making way for the expansive indoor pool and art gallery. Circular skylights are the only indication that such a space exists under the sloping ground, adjacent to a wooden picnic table overlooking a wonderfully manicured rose garden beneath the snow-capped mountains.

The spacious, three-story home now boasts all the amenities you could desire, from a home theatre to a large wine cellar as well as a sauna, an elevator and newly formed large bay windows. Solid oak flooring within and basalt on the exterior keep the materials grounded by nature, while the surrounding stone walls are made of shahhar, a local stone in varying shades of brown and dark red.

The interior, which stayed mostly true to the original layout, but with increased ceiling heights and an open plan, was designed around the owners’ imposing modern art collection. The client’s decorator furnished the home with contemporary modernism, including collectible vintage seating by French designer Jean Royère, a mid-century designer known for his colourful, organic style and precious materials. The result is a luxurious home that blends modestly into its surroundings, an ode to the past, equipped for the future.

PHOTOGRAPHER: RICHARD SAAD