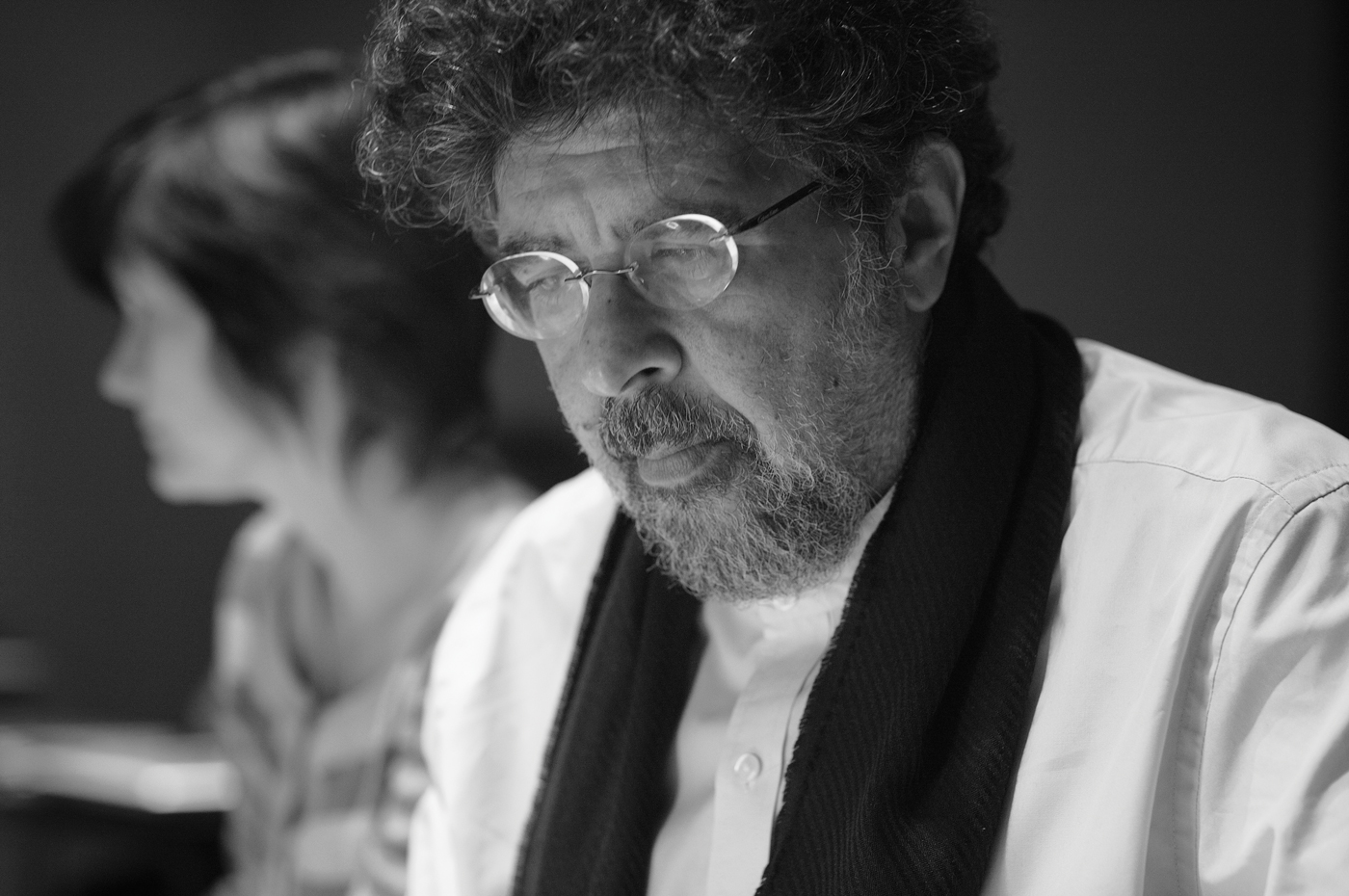

Gabriel Yared had me at “hello”. For a world-renowned multi-talented musical genius, Oscar-winner, international award winner, composer, captivating conductor and self-taught pianist, Lebanese-born Yared is modest, courteous, warm and an extremely likable individual. In short, this genuine human being is arguably one of this era’s most influential composers. Through his memorable compositions, he has awakened the love of music within the hearts of many.

Gabriel Yared had me at “hello”. For a world-renowned multi-talented musical genius, Oscar-winner, international award winner, composer, captivating conductor and self-taught pianist, Lebanese-born Yared is modest, courteous, warm and an extremely likable individual. In short, this genuine human being is arguably one of this era’s most influential composers. Through his memorable compositions, he has awakened the love of music within the hearts of many.

Born in October 1949, Yared attended a Jesuit boarding school in Beirut before leaving the country at the age of 18. Since early childhood, he passionately embraced music. He nurtured this unquenchable thirst by reading the classical works in the school’s library of music whilst remaining receptive to all genres of music. At age 14, he wrote his first composition: a piano waltz. Yet, his piano teacher decreed that Yared lacked the necessary talent and had no future in music.

In 1971, while visiting his uncle in Brazil, Yared was asked to compose a song for the World Federation of Light Music Festivals. It won first prize. This was the beginning of bigger and better things to come. An increasing number of influential people began to recognise his talents, and he began working as a composer and musical arranger for the likes of Johnny Hallyday and Sylvie Vartan, Enrico Macias, Charles Aznavour and Gilbert Bécaud.

His first encounter with motion pictures was in 1973. He worked with Samy Pavel on Miss O’Gynie et Les Hommes Fleurs. In 1979, he was invited by Jean-Luc Godard to score Sauve Qui Peut. From there, Yared went on to compose up to seven original scores per year. His moody electronic compositions for Betty Blue and his captivating score for The Lover both won Césars (French Academy of Cinema Awards).

In 1997, he was catapulted into international stardom. That year, Yared received an Academy Award, a Golden Globe and a Grammy Award for his unforgettable, beautiful and dramatic score for the blockbuster, The English Patient. Since then, apart from picking up more international awards than shelves can display, Yared was also nominated for two other Academy Awards for The Talented Mr. Ripley (2000) and Cold Mountain (2004). It appears his piano teacher was wrong.

As if by divine providence, almost everything Yared does is historic. His first-ever concert appearance in Lebanon at the 2009 Beiteddine Festival was an astounding success. Yet, despite the fact that he has been visiting Lebanon regularly with his son since 1992 to see his parents, why did it take him almost 40 years to perform in his own country? “Nora Jumblat invited me to perform at the Beiteddine Festival in 2006, but there was a war at the time,” he tells me. “I was also invited by the Byblos Festival organisers, but unfortunately, there was always something happening that prevented it. So, this year marks the very first time I performed in my native country, and it’s a fantastic feeling. To add to it, I actually performed by playing the piano and conducting my own music. It was something I’d never done before. It’s a one-off, and it was a very symbolic experience at the turn of my 60th birthday.”

Here it has to be said, Yared doesn’t look a day over 45. So there must be secret somewhere and maybe I, too, will look this good at 60. Using my verbal prowess, I extract the clandestine. “Well, maybe it’s because I still have all my hair!” I then ask why performing in Lebanon was so symbolic. Given all his worldwide concerts, wasn’t this just another run of the mill affair? “Well no. This concert was for my compatriots, my family and friends. I wanted them to appreciate first-hand the evolution of my music through the decades.” And that’s what Lebanon specifically, but the Middle East in general, witnessed: a gifted Arab back on his home soil, baring his musical soul for one night only.

With an Oscar, Grammy and Golden Globe in hand, and more awards than one can count bearing his name, how does it feel to be recognised and honoured in this way? “Fantastic, in a way, but there’s a positive and negative aspect to this type of recognition. The positive is that Hollywood industry professionals finally acknowledge that you have… a certain… call it, talent, gift or skill. But success of this nature also largely depends on the quality of the film. I’ve worked on films that were less celebrated than The English Patient, but brilliant in their own right. I’ve been nominated for the Oscars three times. I got it in 1997 for The English Patient, and I was nominated again in 2000 for The Talented Mr. Ripley and then in 2004 for Cold Mountain. My friend, Anthony Minghella, who passed away last year, directed the three movies. He was a blessing to me, because he was so talented.”

This prompts my next question – what qualities must a movie have for the team to receive this type of iconic recognition? “It must be a truly global movie to achieve such distinction. It has to be a fantastic story with great actors and a great score. Worldwide promotion and publicity also play a major role; otherwise, you don’t get to the Oscars.”

So, there’s a downside to the Oscars? Few celebrities talk about this. What are the negatives? “Unfortunately, in Hollywood, you tend to become very quickly pigeonholed. For example, professionals will conclude that Gabriel Yared is a good romantic, epic or lyrical score composer. As such, one is offered films, which are similar to The English Patient, but less creative. That’s what happened to me between 1997 and 2000. But my music and style is very eclectic. I love funky music, epic music, lyrical music of course, and comedy, and this is what some people in Hollywood fail to see. But, when I was nominated a second time for The Talented Mr. Ripley, I was in effect being nominated for a thriller and my music was completely different’.

Ah, so there is a way to circumvent being pigeonholed in Hollywood. What technique does Yared bring into play? “I single out films, depending on the director and the story. I like to see myself as a measured and refined composer. I like to take my time in composing. I believe in doing less, but doing it better.”

Although Yared’s Hollywood projects ran smoothly, a controversial involvement with the runaway success, Troy, in 2004, resulted in disaster. He was fired. I want to hear his side of the story. “It’s no big deal. These things happen all the time there. It has happened to many of my colleagues: Don Williams was fired, Enya Macaroni was fired and even Stravinsky, the 20th century’s foremost composer, was fired. Being fired wasn’t the issue. My problem was that I had spent a year and a half working on Troy, and the director, producer and studios in Hollywood were completely over the moon with my music. Yet one day during the final stages of recording, I received a call from Los Angeles informing me that I was fired. I was told an audience didn’t like my music during a test screening in Sacramento. I felt let down by the very same people who praised my work; it was disappointing on a human level and not really a professional one. Initially, I was angry. But in retrospect, I’m lucky not have been a part of Troy, because frankly, I don’t think it’s that great.”

I agree; it’s not my favourite movie either. However, Yared quickly bounces back from setbacks through a positive outlook. He shares his personal philosophy with me. “To be honest with you, I’m never looking for anything; it kind of comes to me. Maybe it’s because I’m lucky, but it takes time. It always takes time. One must never think that he or she has made it. No one is ever there. It takes time to impose your music and quality. And, quality always takes time to create. That’s why, these days, I don’t do many movie scores. This year, I did only two.”

For Yared the music always comes first. To delve deeper into the mind of this phenomenal musical genius, I ask him to share with me the method he uses to compose award-winning scores. “The way I approach movie scores is very unorthodox. I like to read the scripts, talk to the director and become fully involved in the project before the actual shooting takes place, because it gives me time to come up with something truly unique.”

Now this sounds interesting. I thought that composers watched the movie for inspiration. How can he compose a score solely from his imagination without actually watching the story come to life on the Silver Screen? “After reading the script and speaking to the director, I look inwards and search for the images being imprinted in the depths of my soul. When shooting starts I begin to match this tune to that image in all the rushes the editors send me. And very often, I’m accurate in my assumptions. However, when the film is finally in front of me, it’s my job to craft and compose every theme and orchestration for each scene. My approach involves marrying the overall spirit of a film instead of focusing on scenes.”

No truer words were spoken. Even the greats, such as Mozart, looked within to write compositions that have withstood the test of time. But aren’t the tight Hollywood deadlines a hindering factor to creativity? “Sometimes. I could score a film in a week; it’s not a problem for me. I’m blessed enough and inspired enough to do that. The problem is that I don’t want my work to become routine, and secondly I consider every new project has to push my creativity beyond my boundaries and habits. This is what takes time.”

I had read that Yared was scoring a new movie in Hollywood. I ask for the details. “I just finished Amelia. It’s a film based on the true story of Amelia Earhart, the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, in the 1930s. After a world tour, she disappeared in the Pacific. Nothing was ever found. Mira Nair, director of Vanity Fair, Monsoon Wedding and Salaam Bombay, directs this film. The lead actors are Hilary Swank as Amelia, Richard Gere as her husband, and Ewan McGregor as her lover. I recorded the score at Abbey Road Studios, London. It took me almost five months to complete.”

After the concert in Lebanon and Amelia, what comes next? “For 2012, I am preparing an opera based on the Prophet by Gibran Khalil Gibran with my friend Amin Maalouf. Amin is a fantastic writer, he writes opera, politics – the lot. He is an amazing and brilliant person. Amin was my classmate in Beirut. We studied together from the age of four to 16. So we go back a long way. This project will give me a breather from the film industry. It’s a difficult project but it brings together three Lebanese people, Gibran Khalil Gibran, Amin and myself, that were in a way exiled from their native country, but remained Lebanese at heart and blossomed abroad.”

I ask if he has any other ‘big’ projects in the pipeline. “There’s no such thing as a ‘big’ project for me, there’s every day. The present is more important than tomorrow. Today, I’m working and composing. I don’t compose just for offers; I compose to breathe. So project-wise, I don’t know what’s next. But God will always provide me with enough of the right things to continue.”

Despite his overwhelming success, Yared is proud to be Lebanese. “Lebanon has provided the world with fantastic people. I recently heard of playwright Wajdi Mouawad, an internationally acclaimed Lebanese-Canadian writer. The sons and daughters of Lebanon are unique and interesting people. Thank God, such a small country gave birth to so much talent, and wherever they go, they remain Lebanese. Even though I’m not into Oriental music and I enjoy French citizenship, Lebanese blood runs through my veins, and consequently, my compositions.”