“What I love about poetry is the freedom that comes with the page and what you can do with the blank spaces. You can do almost anything – even defy the confines of grammar – it’s like the abstract art of the literary world,” says Danielle Badra, the latest winner of the Etel Adnan Poetry Prize, an annual award granted by the King Fahd Centre for Middle East Studies at the University of Arkansas. The prize, which is bestowed once a year to a poet of Arab origins, comes with a 1,000 USD cash bonus, as well as the promise to publish a full-length book.

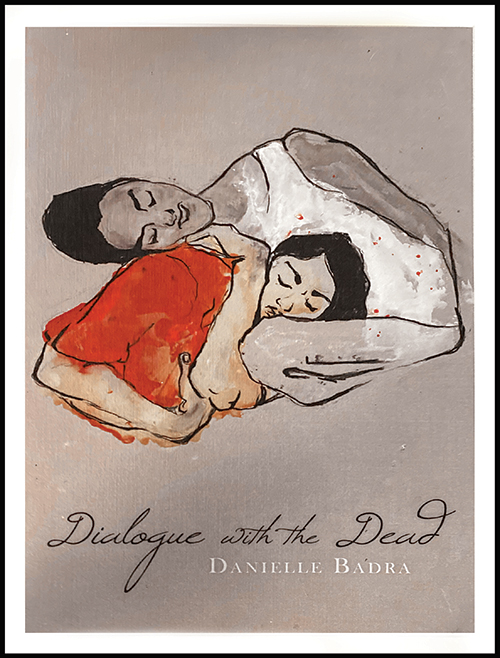

Badra is an emerging name in the world of poetry and first came to prominence in 2015 with the release of a chapbook entitled ‘Dialogue with the Dead’. This profoundly personal work includes a testimonial by the Juniper Prize-winning poet, Diane Seuss, who was Badra’s professor at Kalamazoo College and someone who Badra credits as being a huge influence on her becoming a poet. “This collection,” vouched Seuss, “manages to be deeply human and devotional, intimate and cosmic. Badra’s dialogue reminds me that poetry at its best is not an invention of the ego but of the spirit.” Indeed, this touching compilation exemplifies the adage about poetry being a painting that is felt, not seen.

“It all started when my sister suddenly died in 2012. We were very, very close,” says Badra about her sibling, Rachal, who like Danielle, studied creative writing, and at the same university in Michigan. According to Rachal’s friends though, she never liked to share her poetry with Danielle as, in terms of talent, she felt she was inferior to her younger sister. “When Rachal died there were a lot of unresolved matters and I really needed to talk to her. So, when I came across a folder of hers filled with poems that she had written about facing death and her out of body experiences, I really needed to respond because I had never even known what was happening.”

“It all started when my sister suddenly died in 2012. We were very, very close,” says Badra about her sibling, Rachal, who like Danielle, studied creative writing, and at the same university in Michigan. According to Rachal’s friends though, she never liked to share her poetry with Danielle as, in terms of talent, she felt she was inferior to her younger sister. “When Rachal died there were a lot of unresolved matters and I really needed to talk to her. So, when I came across a folder of hers filled with poems that she had written about facing death and her out of body experiences, I really needed to respond because I had never even known what was happening.”

As it turns out, Rachal had been suffering from a rare medical disorder that would cause her heart to sporadically stop and start. Her family, including her only sibling, Danielle, had initially thought Rachel was suffering from bouts of fainting only to later realise these were in fact cardiac arrests.

“I really wish she had shared her poetry with me while she was alive,” says Badra, who didn’t just find inspiration in her late sister’s words but a means to defy her death and remain in communion with her. She did so by taking each line of Rachal’s writing and intertwining it with her own, creating a single composition called a contrapuntal poem. “I ended up writing around 350 of these contrapuntals. I would always keep Rachal on the left and I would be on the right. I just became so obsessed that, by 2014, when I was going to start my Master’s in Fine Arts [at George Mason University], I was really nervous that I couldn’t break out of that form anymore. In the end, I’m really grateful I did the MFA because apart from the fact I learned new skills, studied new poets, and my poetry world opened up, it also helped me break free.”

Badra says that her forthcoming book, ‘Like We Still Speak’, (University of Arkansas Press) is a “gallery of voices” that she has collected in her life so far, including that of her late father, mother, a few friends, some poets she admires (but never met), as well as her partner Holly Mason, whose poem ends the book. “I used a lot of different forms to highlight those voices. The book comprises 68 poems or so, and they’re all deeply personal once again but I also touch upon more international events this time, including the war in Syria.” Essentially, what ties the book together is Badra’s mastery of language and her ability to express emotions in accessible conversational forms.

As a recipient of a prize that promotes English poetry by Arabs, I ask Badra how life is these days for someone of Middle Eastern descent in America. “9/11 created a big shift in my identity. I was 15 at the time and from that point on I really wanted to know more about my heritage, which is both Syrian and Lebanese,” confides Badra. “But winning the Etel Adnan Prize was really special not just because it’ll help propel my career forwards but because I was able to share with my father, just two months before he passed away, that I was going to get a full length book published and that it was thanks to a prize which honours somebody of Arab heritage.”

Finally, I ask Badra if she has any advice for aspiring writers. “It’s important to establish your own voice, don’t give up and keep submitting and revising,” she says. “Trust in the process of submitting and revising because eventually someone will see what you’re doing and then things can get picked up from there.”