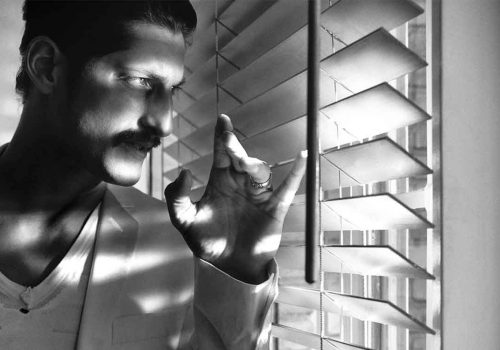

Beirut-born chief executive Malek Sukkar speaks to me via video conference from his Dubai office looking ready to do business in a white shirt and dove-grey tie. It’s currently what he likes to call the Emirate’s “palatable season”. Behind him, the mid-afternoon sun streams through the floor-to-ceiling windows and a triptych frame holding photos of his three children takes pride of place on a desk.

The first topic of conversation isn’t his achievements – his world-leading sustainable waste management company, Averda or his seat on King Charles’ Sustainable Markets Initiative – but the English Premier League. “Liverpool FC woke me up to life,” he says. “Growing up in Lebanon, we only got news of the league leaders, so Liverpool became my true love from the age of seven or eight, before we moved to the UK in the early 1980s.” It’s a passion he has passed on to his children. “We’re a Liverpool family, even though we live less than 2.5 kilometres from Stamford Bridge and 1.5 kilometres from Queen’s Park Rangers.”

ABOVE: A trained engineer, Malek joined Sukkar Engineering in 1994, two years after graduating from Boston University. Six years later, in 2000, he became CEO of the newly consolidated Averda Group. He is also a Board member of Growthgate Capital, a Trustee of BU and a founding member of WEF’s Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE).

But despite Sukkar’s admiration for the flair of Anfield legends like Kenny Dalglish and John Barnes, his true role model is his father, who gradually handed him the reins at Averda between 2010 and 2012.

These family foundations underpin the company’s success. Averda ‘cleans up’ across nine countries and three continents with a 17,000-strong workforce. “My father was always working away, but he made an amazing effort to keep the family as a unit and did a fantastic job,” he explains. “We formed a great partnership. I had been running the business from an operational level for a long time, yet he always made sure that the culture and the aspirations of the business aligned. He’s been a great mentor from the very first day, but also forced me to make some difficult decisions at the beginning of the business.” Like his father, he wants to make sure that his industry still attracts the brightest future minds.

These days Sukkar literally keeps his feet on the ground by running. At 53, he looks trim for somebody who says he sits at a desk 80 per cent of his time. It’s his guilty pleasure and he packs his trainers and light outerwear whenever he is jet-setting around the world. “It’s not only therapeutic from a physical perspective, but also for my mental health – my form of meditation. I listen to audio books or podcasts and it connects me with a part of my brain that I don’t activate during the day,” he shares.

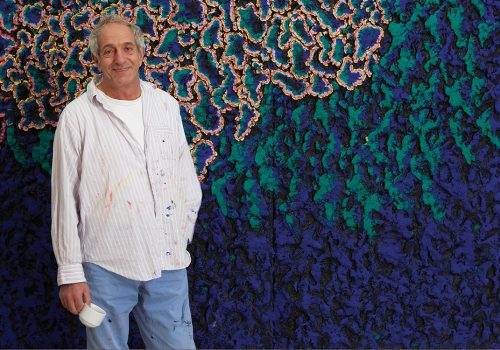

Then there’s the museum-worthy art collection that he’s established with his wife Maria Sukkar, a renowned expert in the field. Sukkar describes it fondly as “something from the heart.” He particularly admires the “wonderful strong beauty” of Jenny Saville’s oils and Thomas Houseago’s “meaningful” sculptures. “I’m petrified at the thought of drawing a chair,” he says modestly. “So, I’ve always appreciated the amazing talents of those who are able to use their talent to project their fears and aspirations to the world. Whenever I am surrounded by art it takes me to a different place where things are either hyper-real and scary, or hyper-ideal and inspirational. Depending on the day, I like to be in one of those two places.”

Helming the emerging world’s leading waste and recycling company is no mean feat, but Sukkar remains down to earth and pragmatic in his manner and sees Averda as a local business. “Our business is people’s waste and how they deal with it – it’s very specific to the market in which we operate. Rules in Saudi Arabia are very different to rules in Morocco, South Africa and India. But the standards, expectations and professionalism are always the same. We make sure the service and level of satisfaction is the same but serve our clients to maximise local legislation.”

Sukkar explains that companies like Averda are closing the gap in a circular global economy, by collecting discarded waste and preparing it for reuse. “We are in the right business at the right time. People take a very clear view of circularity today and, thankfully, it has given us a big market and we have grown significantly over the last ten years.”

Last year Averda’s responsibilities to the planet stepped up when they received a 45 million USD investment loan from the US government’s International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) to create plastics recycling facilities in Africa and India and divert materials from landfill. “The more we can get institutions like the DFC and IFC to help us with funding and make sure the markets in which we operate are better served; the better it is for the world.”

This social conscience is evident on Sukkar’s Twitter feed. The graphic on his profile page isn’t Averda’s corporate logo or a catchy marketing strap-line, but an image of the ocean and a sea turtle captioned ‘our world without waste.’ I ask him if he sees himself as an environmental influencer. “No,” he replies without hesitation. “I’m someone who is influenced. If you dive into the ocean or drive in the mountains, you see the damage that we humans do. We can’t be oblivious to this reality.”

Despite citing his deep knowledge of the economics of pollution – he explains that cleaning-up was once around ten times the initial cost of the pollution – he doesn’t class himself as a ‘big thinker’ like Al Gore, or Unilever’s Paul Polman. “There’s no shortage of thought or opinion, but there is a shortage of action. I put myself in the second camp. So, those guys can do the thinking and we can do the heavy lifting. We need to make sure that plastic doesn’t end up in the ocean and food doesn’t end up in landfill – we’re putting our money where our mouths are.”

But, isn’t he concerned that the world won’t meet the UN Biodiversity Conference COP 15’s 2030 targets to “cut global food waste in half and significantly reduce over-consumption and waste generation”?

“It might not happen by 2030, but if it happens by 2035, we’re still in better shape than if we had just given up and not done anything.” It’s that pragmatism talking again.

Photography: Ilan Godfrey & Thais Breton