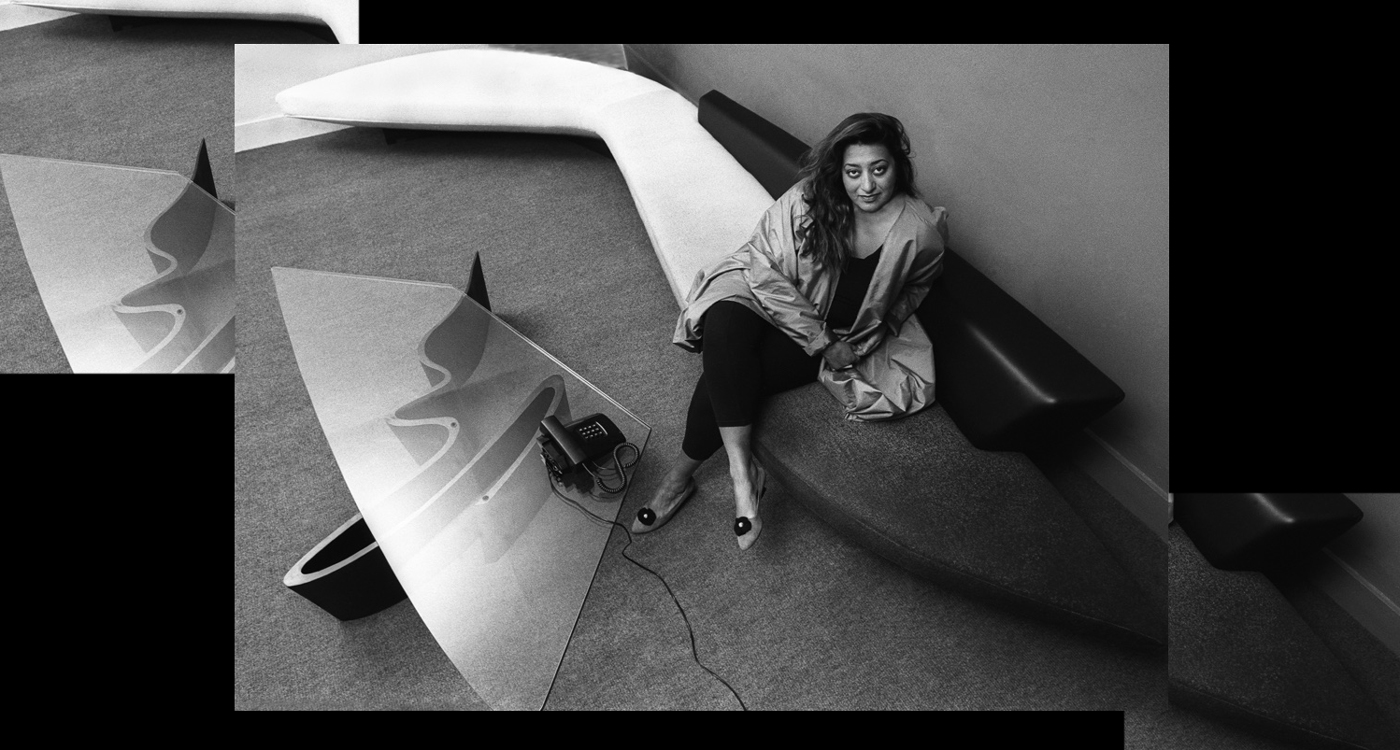

When she was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize for Architecture in 2004, Iraqi-born Zaha Hadid was not only the first Arab to win but also the first woman. Her work is both genius and thought provoking with multiple perspective points and fragmented geometry supposed to evoke the chaos of modern life.

The Club lounge concierge and I arrive at Zaha Hadid’s suite at the Phoenicia Hotel at the same time as two maids from Housekeeping. We ring the bell. A minute or so later, Hadid opens the door and is momentarily nonplussed by the presence of not one, but four unfamiliar faces at her door.

She is smaller than I had expected. Not, you understand, that I had given any thought at all to how tall Zaha Hadid might be. It’s just that given everything I have heard and read about her, I honestly wouldn’t have been surprised if the door had opened to reveal a 2-metre tall Amazon, such is her stature on the global stage.

So delirious – to borrow a favourite adjective from her former mentor, friend and fellow starchitect, Rem Koolhaas – is Hadid’s reputation that you would almost have to have spent the last 10 years under a rock, or else in a nunnery, not to have heard of her at least once. The woman, who once said that as there are 360 degrees, she could see no reason to restrict herself to just one, is in Beirut for two reasons. The first is to visit relatives – Hadid and her family left their native Iraq at the start of Saddam Hussein’s reign – and the other is to follow up on a couple of the projects she has, or soon will have, underway.

These include the Issam Fares Institute on the American University of Beirut campus, a strikingly sculptural department store for the Beirut souqs she is planning with Aishti owner, Tony Salemeh, an interior design project for the headquarters of the Mawarid Bank and, rumour has it, maybe even a museum for Baalbek too.

Hadid knows Beirut intimately. She studied here during the turbulent, politically charged years of the early 1970s, graduating from the AUB with a degree in mathematics, leaving just before Lebanon descended into its civil wars to study architecture at the AA in London, where she has lived ever since.

Hadid knows Beirut intimately. She studied here during the turbulent, politically charged years of the early 1970s, graduating from the AUB with a degree in mathematics, leaving just before Lebanon descended into its civil wars to study architecture at the AA in London, where she has lived ever since.

Looking out of the window at the evolving city/reconstruction site that is central Beirut, I ask her if coming back is a saddening experience, given how drastically the city has changed since she was a student.

“No, I like it, there’s still a buzz here,” she says, before adding that the reconstruction of the city has wiped away so much of Beirut’s past. “It’s just that as an architect, you always look at things and think ‘I wish they’d done it that way’.“

I feel compelled to dig and so I ask what she would have done differently. Of course, the question is unfair, both to Hadid and to Beirut. Rebuilding a city ruined by war is never an easy thing and it is easy to criticise with hindsight.

“They had to erase the war, they had to do something immediate because if they hadn’t done something, it would still be rubble, frankly,” she says, with the assurance of someone who has pondered the question many times before. “So I understand the desire and the need to stitch it all back together but I think the strategy wasn’t right. I came here 12 years ago and it was still in ruins, you were standing here by the sea and you could see every layer, read the city despite everything. Whoever was working on the city completely misunderstood it. They made a tabula rasa. Beirut is not Berlin. Berlin has a thousand blocks, Here, they have ten. Tearing it all down doesn’t work.”

Neither, of course, does leaving everything in place but then that isn’t what Hadid is suggesting. Rather, she believes that those who rebuilt Beirut tried to do so in an overly simplistic way, one that ignored what she calls its ‘layering’.

“I think they are quite conservative here but actually an extreme approach [to reconstruction] would have been more relative, more what this city is about,” she says. “Historic cities like Beirut were all based on complexity, layers of history and use, they went here, there, everywhere.” A bit, I wonder naughtily, like her buildings?

Hadid has said in the past that she is inspired by “the compelling beauty of living organisms”. This is perhaps why although her buildings can be hard, angular and asymmetrical, nothing if not (wo)man-made, they also exude an energy and fluidity more reminiscent of organic than mechanical structures. It must also be why, despite the rather startling impression they can give of being alien artefacts, even her most otherworldly buildings do not, on reflection, appear to have landed from space as much as they appear to have sprouted from the ground.

“People ask why are there no straight lines, why no 90 degree angles, well, life is not made in a grid. Now, it could be interesting at times to have a grid but if you think of a landscape, it’s not even, it’s not straight. People go to natural places and say it’s very relaxing. I think that one can achieve the same thing in architecture.”

Certainly, Hadid is trying. Even when captured in something as static as concrete, her designs aren’t fully at rest. Long flowing walkways, rippling walls, unusual intersections and her innovative division of interiors, frequently conceived as a single morphing space that eschews obvious hierarchy, all contrive to keep the gaze, the feet and the mind, moving.

Take her extraordinary fire station in Weil-am-Rhein, with its sharply angled-roof, a little like a launchpad and walls that almost seem to be sliding past each other. Or the dynamic Bergisel ski jump in the hills above Innsbruck, a structure that is imbued with so much coiled energy, it only barely manages to keep still and which poses the question as to whether it is the jump or the skier that is about to take off. Then there is the Rosenthal Contemporary Arts Centre in Cincinnati, a giant puzzle box of a place made up of interlocking concrete slabs and glass walls and, most recently, the audaciously cantilevered Phaeno Science Centre in Wolsfburg, every part of which is forced to ‘multi-task’, effectively erasing the line between the building’s structure and its function but unlike, say, Paris’ Pompidou Centre, to sculptural rather than industrial effect.

“My architecture is different things at different moments. The last 10 years have been a quest to achieve the ultimate in mobility and fluidity,” she says. “I understand when people say my buildings are extreme. They do not belong to this boxy kind of world that everyone’s used to. If they have become more extreme, it’s because [increasingly] they have had to accommodate so many different needs in a single solution.”

“My architecture is different things at different moments. The last 10 years have been a quest to achieve the ultimate in mobility and fluidity,” she says. “I understand when people say my buildings are extreme. They do not belong to this boxy kind of world that everyone’s used to. If they have become more extreme, it’s because [increasingly] they have had to accommodate so many different needs in a single solution.”

In addition to projects in Beirut and a prize-winning entry for a cultural centre in Amman, Hadid is also working on several much larger-scale projects in the Gulf. There is an apartment complex in Dubai, dubbed the ‘Dancing Towers’ for the way they appear to bend and flex; the Dubai Opera House, sinuously interlocking curves that appear to have been sculpted by wind and water; then there is the magical water-front Performing Arts Centre on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island cultural complex, which looks from renderings like it will be built from frozen water and butterfly wings.

As for inspiration, in previous interviews, Hadid has spoken of trips to the floating villages of the Shatt al-Arab and of her admiration for the early Modernists and the Russian Avant Garde. Less expected is the role the past plays in the vision of such an uncompromisingly futuristic designer one who, almost single-handedly, has redefined what a building can mean, creating in the process the first genuinely 21st Century architectural aesthetic.

“I went to see the Umayyad Mosque [in Damascus] a few years ago and I was told that everything, the floor, the walls, the columns, the ceiling, everything used to be covered in mosaics. Can you imagine someone walking into that kind of space back in those days? It must have been heavenly, I mean literally, a heavenly space on earth,” she says. “This connects back to a very contemporary idea, the idea of seamlessness. I think people have always aspired to invent such spaces, and it isn’t easy. It is uplifting to go into a great space, a heavenly space, that’s why over the centuries people have invested so much time to make it possible.”

Recalling her time at AUB, I ask Hadid if she ever imagined she’d be building in Beirut and beyond that, what it is like to be building in the Middle East. “Because I’m an Arab, it means a great deal to me,” she says, “but working here is totally different to everywhere else.”

I hesitate to ask exactly what she means by that, if only because I suspect it may have something to do with the ‘I want it now, I want it big and I want it for at least 50 per cent less than you’ve quoted’ attitude that, if not unique to the region, does heavily pervade this part of the world. But I am curious to know what she makes of the instant cities of the Gulf, especially given her fondness for history.

“I love Dubai,” she says, “if only because I think that it conveyed a message of optimism for the Arab World, it showed a degree of optimism and enthusiasm and the ambition to compete, to make great things and surely that’s not such a bad thing.”

But what of Dubai’s urban planning, the dependency on cars, the traffic bottlenecks, even the quality of its hastily erected buildings? “The urban planning was not up to the game. [Dubai] is based on one strip and the strip city is not a new idea and not necessarily a good one. But there are not many places where you can actually demonstrate,” she pauses, collecting her thoughts, “where you can build what you mean by certain ideas and it was possible there for a while. I think that’s very exciting.”