Let’s take a moment to look into the not-too-distant future. Imagine that a robot has stolen your job and pushed you into a lower-wage occupation, if not out of the workforce altogether. Now, this isn’t science fiction, for a University of Oxford study estimated that due to advances in artificial intelligence and automation, 47 per cent of US jobs may be at risk within the next two decades. Moreover, last year, the White House Council of Economic Advisers estimated that workers making below 20 USD an hour would have an 83 per cent chance of losing their jobs to robots in that span. The odds drop as workers’ education and income levels grow but as software gets smarter, that too is subject to change: companies will eliminate even the jobs that were previously considered immune from technological displacement.

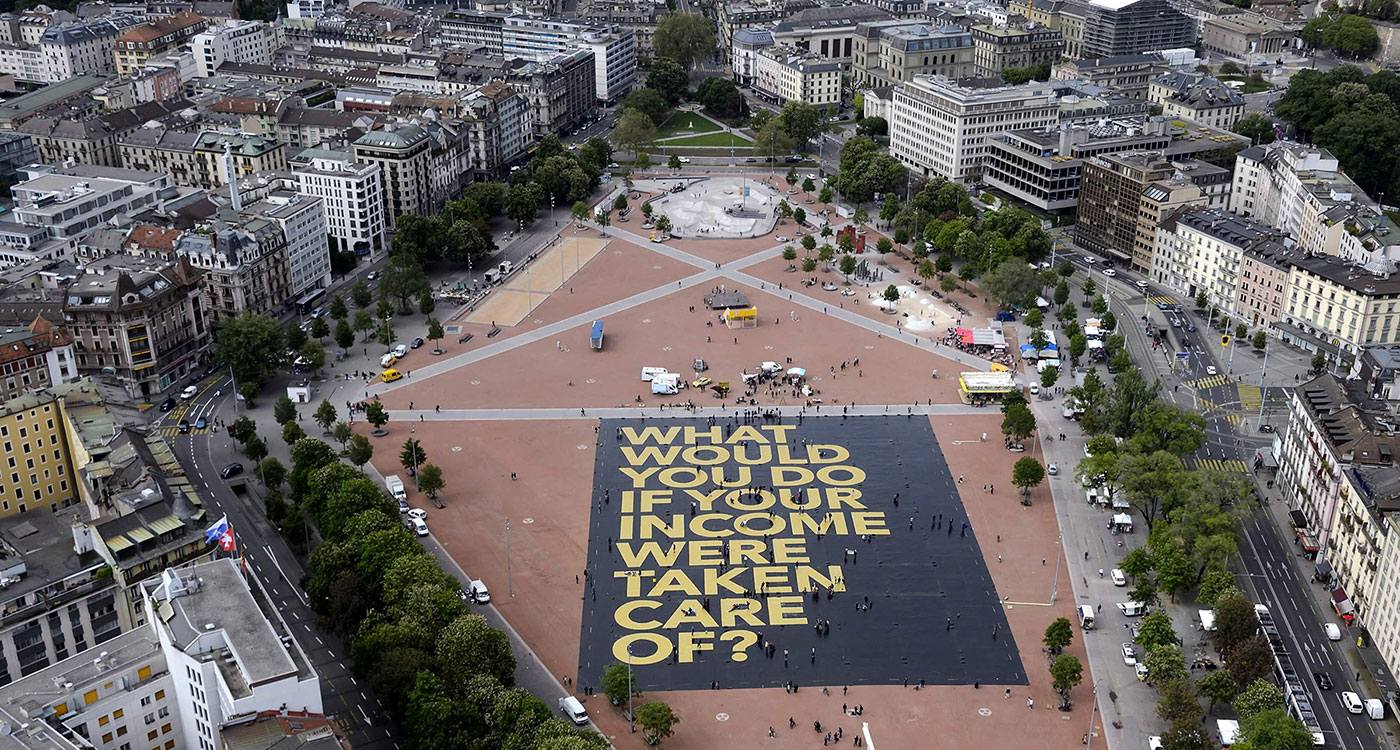

This brings us to the only viable alternative to anarchy and mass uprising: UBI. But, how does it work? Well it’s simple really, everyone regardless of whether they have a job or not, receives a fixed sum, let’s say 1,500 USD a month, with no strings attached. So, what would you do with that? Would you travel? Pay down some bills? Give it to a relative in need? Maybe go back to school? Would you even bother going back to work? UBI raises many questions but that’s because it’s nothing less than the most ambitious social policy of our times. And while it has a growing number of high profile endorsers – including the world’s best-known CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, who made a case for it during a speech at the 2017 Harvard commencement when he said, “We should have a society that measures progress not just by economic metrics like GDP, but by how many of us have a role we find meaningful. We should explore ideas like Universal Basic Income, to make sure that everyone has a cushion to try new ideas” – it also has its fair share of critics who claim it will undermine productivity by rewarding laziness.

This brings us to a 2013 study by the World Bank that specifically examined if poor people waste their handouts on alcohol and tobacco when they receive it in the form of cash. The clear answer was that they don’t. In fact, the World Bank found the opposite to be true, in that the richer you are the more likely you are to consume alcohol and drugs. It would seem then that the lazy drunk welfare abuser is a false stereotype. So what data is there on laziness? In fact, minimum income studies conducted in Canada in the 1970s showed that just 1 per cent of the recipients stopped working (mostly to take care of their kids) and on average people reduced their working hours by just ten per cent with the extra hours being used to go back to school and look for better jobs. That sounds amazing right?

Sure, but is UBI even affordable and what will it do to inflation? If everyone is richer, then surely prices would just rise and end up leaving everything as it was before? The answer to that is, since the money is not being created by magic, or printers, it needs to be transferred from somewhere, hence UBI is actually more of a shift of funds than the creation of new ones, and that means inflation won’t be an issue. Nevertheless, the answer to how states would afford UBI is not so straightforward. It would first require a consensus as to what kind of UBI we want and what we are willing to give up to pay for it. The simplest solution though would be to abolish welfare entirely. Not only would this jettison a lot of government agencies (and create further savings), it would also eliminate a lot of bureaucracy.

Interestingly, a recent study in the US showed that a UBI of 1,000 USD per month would actually grow the GDP by 12 per cent over 8 years, as it would allow poor people to spend more and thus increase overall demand. Still though, before we hail UBI as the saviour of society, there needs to be a lot more research, including more and bigger test runs. But its potential is huge and it certainly looks like it has the power to be the most promising model to sustainably eliminate poverty. What’s more, it could also make humankind happier, and that’s one thing we can all get behind.