Picture a successful fashion designer 50, 20 or even ten years ago, and you’d likely be thinking of a white man tailoring evening gowns in London or Paris. But today, one of the world’s most watched, most discussed designers is a black man from Chicago; the 37-year-old son of Ghanaian immigrants no less. He arrived in fashion with a degree in civil engineering and another in architecture, he designs as many hooded sweatshirts as dresses, and his clothes sell out across Europe, Asia and the US at prices that might make your eyes water. And his rise to head up Louis Vuitton’s menswear makes him only the third black man to take the helm of a major heritage fashion house (after Ozwald Boateng, who headed up Givenchy men from 2003 to 2007, and Olivier Rousteing, who’s still the creative director at Balmain).

For his cooperation with Nike, Abloh created ten new silhouettes by reconstructing ten of their most iconic models. The incredibly sought after shoes were then sold in limited supply at dedicated ‘Off Campus’ pop-up shops around New York and London.

Virgil Abloh is the polymath behind the brand Off-White. If you’d heard of him five years ago, it would most likely have been in connection with Kanye West – Abloh has been on the rapper’s team as a creative consultant since 2002, with input into everything from sets to tour merchandise (“We’re still very close,” he says). But it was in December 2013 that he launched Off-White, taking the American street style born of 1990s hip-hop and throwing it straight into the polished, expensive world of high fashion.

I probably wouldn’t have done this interview if I didn’t think 17-year-olds would read it and be like, ‘Wait, I have good ideas, I’m articulating my culture, I can possibly end up successful, too.

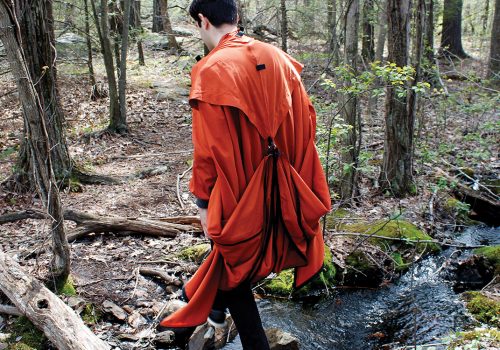

Four years later, Abloh’s reputation within that industry has grown exponentially and outstripped that of his famous friend (West has his own clothing brand, Yeezy). Off-White’s designs are worn by a flock of A-listers, mainly of the type we follow in our millions via Instagram: Rihanna, Kendall and Kylie Jenner, Kim Kardashian, Beyoncé, Justin Bieber, Bella Hadid, Joan Smalls, Solange Knowles. In 2015, Abloh was the only American finalist for the prestigious LVMH Prize for designers. Industry bible businessoffashion.com says that Off-White’s sales grew 100 per cent from 2015 to 2016 (although the company refuses to confirm that figure). Abloh has collaborated with Nike, Moncler, Levi’s and Jimmy Choo and is soon to launch a collection with Ikea. In 2019, there will be an exhibition of his work at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

His latest womenswear show, which took place in September and cited Diana, Princess of Wales, as its surprising muse, was the most exciting of Paris Fashion Week. It was closed by Naomi Campbell, dressed in a sharply tailored, ruffled white blazer and Off-White-logoed cycling shorts. If you think it’s typical for her to make an appearance for a four-year-old brand, you’d be mistaken. “When Naomi walked out, people were cheering and clapping, and they did it again when she came out with Virgil,” recalls Lauren Indvik, head of news and features at Vogue International. “It felt like a real moment of arrival. It was hard to believe that, just two years before, he was doing small runway shows with some white cut-out T-shirts and deconstructed Levi’s.” Previously, the industry had been interested; now, it is on the edge of its front-row seat.

Abloh is a tall, handsome man. He speaks in a Chicago drawl, chooses his words carefully, and bats away topics he doesn’t want to discuss. He answers next to nothing about West, though he will confirm a tale I’ve read about how they met: Abloh located the graphics shop in Chicago where the rapper printed his merchandise, dropped off some of his own designs incorporating the logo of West’s record label, and persuaded the shop’s manager to show West’s team. He was working for him within a month. In 2009, they interned at Fendi together, and later both received mentoring from the esteemed Central Saint Martins professor Louise Wilson. But that’s about it for Abloh’s formal industry education. “Streetwear is my fashion school,” he says.

Top: One of the many Off-White ‘Industrial’ belts that have proved very popular for the brand. Botton Right: The Off-White x Jimmy Choo Spring/Summer 2018 collaborative collection. Bottom Left: A hoodie produced as part of the Off-White x Moncler partnership.

His triumph is a product of several things converging at once. Most obviously, there has been a collective movement away from formality: men can now wear trainers and sweatshirts in contexts where shiny black shoes and a blazer would once have been de rigueur. Off-White is one of the brands that has enabled casual streetwear to climb into the luxury bracket; another is the New York label Supreme – a huge inspiration for Abloh – which recently did a sell-out collaboration with Louis Vuitton. Soon afterwards, investment firm Carlyle Group took a (rumoured) 50 per cent share of Supreme for 500 million USD. Not bad for a label that sells logo T-shirts.

Then there’s the cult of celebrity: Abloh’s starry connections got his name circulating before he had even launched his company. Another factor is the increasingly urgent feeling within fashion that people of colour need to be better represented (and beyond that, that they may be the only ones able to lead the industry out of creative stagnation). You can see it in the recent appointment of Edward Enninful (also the son of Ghanaians) as Editor of British Vogue, and the placement of the British Fashion Council’s model of the year, Adwoa Aboah, on that magazine’s cover.

Abloh also argues that Instagram has been crucial to his success. “I think I might be one of the first luxury brands burst from that platform. I made Off-White from that, I made it thinking about it – it was the only way for anyone to know about the brand. It wasn’t going to be through pages in a magazine.

Had it been five years earlier without social media, I don’t think I would have had the platform I have.” He and Off-White have 3.7 million Instagram followers between them.

There are a couple of magic ingredients particular to Abloh, of course. One is his understanding of the culture around him. “Virgil really captures the zeitgeist in all his projects, which is what makes him important outside the fashion industry, too,” says Ida Petersson, Browns’ womenswear buying director. “He has an effortless sense of what’s going on and applies this across fashion, art and music.”

His other great strength is boundless energy. His “typical African parents” wanted him to be an engineer, hence his first degree. (“They’re still not certain exactly what it is I’m doing, but they’re happy,” he says with a laugh.) On the side, he started to work as a DJ. “The DJing was just as important to me then as school was supposed to be. It taught me how to multitask, how to get three things done on time at the same time, and do it in a certain way.”

Abloh is married to his high-school girlfriend, Shannon, and they have two children aged four and one, yet he takes around 300 flights a year, whether that’s to perform in Las Vegas or to visit Off-White’s office in Milan. How does he manage a personal life? “It’s easy,” he replies, as though baffled by the question. “This is how I work. This is how I’ve always been.

I dedicate every day to being creative and thinking and working. Vacations are foreign to me. Relaxing isn’t my natural pace.” Is your wife the same? “I don’t know that many people are the same,” he says.

His goal was to run a major fashion house – to join the ranks of designers such as Maria Grazia Chiuri, Olivier Rousteing or Demna Gvasalia, who’ve revamped Dior, Balmain and Balenciaga. And the dream has come true thanks to Louis Vuitton, despite rumours linking him to Givenchy and Versace.

He won’t name the luxury brands that he most admires – it wouldn’t be very diplomatic – but says, “I think the ones that are resonating, the ones you see on the street that people are adopting and wearing, are a marker of what’s working.” He is almost certainly thinking of Balenciaga, the 98-year-old Paris fashion house which, under the creative direction of Georgian designer Gvasalia, is now selling offbeat sweatshirts and trainers that have attracted an army of young fans. It’s the same ethos as Abloh’s own brand and, indeed, he has DJed at one of Gvasalia’s aftershow parties.

While Off-White has just launched an affordable-ish capsule collection, For All, which includes T-shirts for 95 USD, equivalent pieces in the main line cost around 320 USD. A new-season varsity jacket costs 3,750 USD. Isn’t there something a bit hypocritical, I ask, about taking fashion ideas from working-class kids and turning them into something that sells for hundreds or indeed thousands of dollars? “Off-White is definitely a contradiction,” he allows. “So I get it if people say, ‘Streetwear is our thing and it shouldn’t be in a luxury space,’ but those questions are more aimed for other brands, not this one.”

His success is likely to open doors for younger people – other designers of colour, anyone who doesn’t come from the narrow, privileged world traditionally associated with fashion. “I probably wouldn’t have done this interview if I didn’t think 17-year-olds would read it and be like, ‘Wait, I don’t have to go to fashion school. I have good ideas, I’m articulating my culture in my little brand and, from my bedroom, I can possibly end up successful, too,’” he says. “To me, it’s a way of paying back for the culture that made me. We were talking about streetwear kids feeling like, ‘Why is this shirt 300 USD?’ The larger picture is that you can do it, too. There’s no golden ticket.”

Abloh may never have been given a golden ticket, but he’s worked his way to a point where the heavy doors of a long-established fashion house have swung open for him. Still, I suggest, bringing his dynamic, always flying, working-with-the-kids approach to one of those unmovable behemoths will be a whole new challenge. “I’m not demotivated by how difficult it could be,” he says dismissively. “I’m inspired by how awesome it will be.”