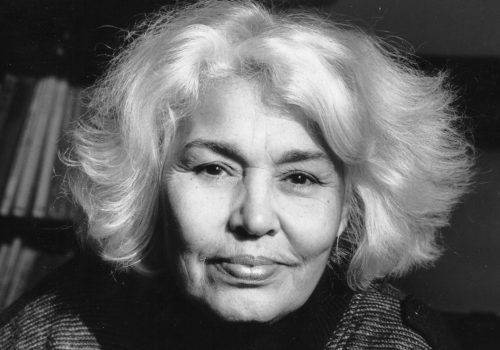

In Nadine Labaki’s office, on the first floor of a well-located Ashrafieh building, you can trace her career, past and present, by looking at the walls. The slapdash approach to decor in the utilitarian space is perhaps a reflection of the year Labaki and her team have had: framed film posters are slapped up next to production stills, printed-out photographs from advertisers and location scouts, hundreds of Post-Its and marked-up whiteboard calendars mapping out the next few months of screenings, releases, film festivals, and, in February, the 91st Academy Awards. Labaki’s new film ‘Capharnaüm’, which she directed and co-wrote, is Lebanon’s submission for Best Foreign Language Film. The team plans to win the Oscar. With a schedule like this, interior design has had to take a backseat.

‘Capharnaüm’ is an unrelentingly dark tale of grinding poverty, institutional injustice, and desperation set in the shadowy margins of Beirut. The film follows two children and an undocumented Eritrean domestic worker as they grapple with issues related to their unacknowledged, paperless existence in Lebanon. Casting an unwavering gaze at difficult issues has helped make a profound impact so far among early audiences: it earned not only the Jury Prize at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, but a 15 minute standing ovation at its screening.

It’s difficult to watch, and Labaki knows it. In fact, she intended it that way. “As a viewer I want you to be stuck in your seat and see what I’m showing you. I’m making you watch it even though it’s uncomfortable. We need to talk about and face this problem, even though it might seem so huge we want to look away. But we need to see it.”

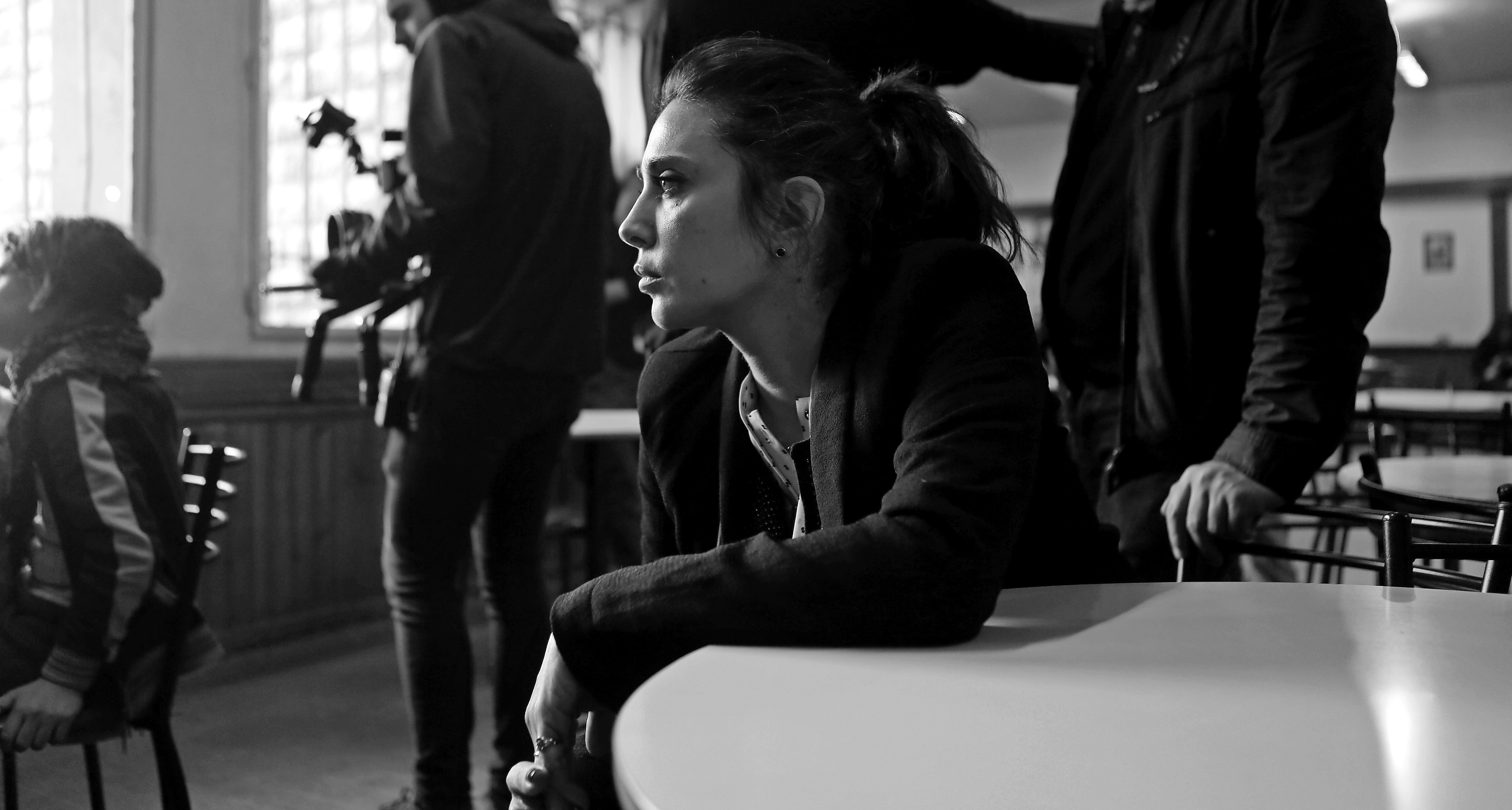

Labaki had breezed into the room where I was waiting among her harried staff, scanned the room for people she didn’t know, then walked over and shook my hand. “Hi,” she said, not bothering with an introduction. She was in a diaphanous, off-the-shoulder black silk top that looked like a continuation of her shiny dark hair.

It’s possible, of course, to recognise that someone is beautiful from seeing them in a photograph or on a screen. It’s also true that Labaki is extremely striking in person, an archetype of Mediterranean feminine loveliness with black hair, luminous olive skin and saucer-like amber eyes. But part of her charm is the way she talks. Sitting in her office, I’m struck by her self-assuredness, honesty and the extent to which she trusts her instincts (that is to say, a lot).

Labaki’s inspiration for ‘Capharnaüm’ comes from a place of anger, and that is clearly manifested in the pic. (Labaki even appears in the film through a cameo role as a public defender, and in court scenes the rage seethes from her huge Bette Davis-esque eyes.) Making a film, she says, “felt like a normal way to express my anger toward injustice, whether it’s paperless children, child labour, domestic workers, the sponsorship system in Lebanon, the fact that people without papers are not allowed to love or have kids or have a life, the fact that we completely dehumanise them. I wanted to turn this anger into something positive.”

Her artistic inspirations include the French cinéma vérité movement from the 1960s, which placed increased emphasis on naturalistic gestures and dialogue, as well as more modern films from Iranian directors. “I’m fascinated with how [these directors] work with actors,” she says. “You don’t feel as though they’re acting at all. The stories are about human nature and human behaviour.”

Reflecting this artistic foundation, Labaki and her casting director Jennifer Haddad sought out non-professional actors for the leading roles in ‘Capharnaüm’, in particular the two children (one of whom, Boluwatife Treasure Bankole, was a toddler at the time of shooting). Both children deliver astonishingly powerful performances; this is due, Labaki says, to her policy of staying out of the actors’ way. “It’s about being aware that we need to be at the actors’ service and not the other way around. I can’t ask Zain [Al Rafeea, the nine-year-old actor who stars in the film] to memorise text. He can’t even read! I can’t ask him to act. I need him to be who he is.”

Haddad and Labaki cast Al Rafeea after seeing him playing in the street with his friends in Beirut’s Nabaa district. Now 13, the Syrian boy from Daraa, who sought refuge in Lebanon with his family in 2012 after clashes began in his hometown, has been working since a young age rather than going to school. “It’s a miracle that we found him,” Labaki says. “I truly believe that Zain is not in this film out of coincidence; he was destined to be in this film. Our casting director sent me a video on WhatsApp as soon as she interviewed him, and we all knew it was him.”

It’s obvious from the film that he is angry too, and he’s not the only one. “In Lebanon there are thousands and thousands of children growing up with no education, who are angry and numb. They’ve been through so much neglect, abuse, rape… there are hundreds and hundreds of girls being married at 11 or 12, thousands in child labour in Lebanon alone.”

Amplifying the voices of the marginalised has been a lodestar for Labaki throughout her career. A graduate of Saint Joseph University in Beirut, she got her start directing music videos for Lebanese pop superstar Nancy Ajram. Though a woman like Nancy probably can’t be described as a marginalised voice, it’s Labaki’s casting of the glamorous Ajram that belies the former’s subversive tendencies; in one famous video for ‘Ah w Noss’, Ajram plays an Egyptian villager, hand-washing clothes on the roof while scolding a pesky stalker. In another, Labaki casts Ajram as the working-class owner of a smoky café who wipes down tables before busting out the requisite sexy dance moves. In a music video climate of glossy, inaccessible beauties, these projects were radical.

Amplifying the voices of the marginalised has been a lodestar for Labaki throughout her career. A graduate of Saint Joseph University in Beirut, she got her start directing music videos for Lebanese pop superstar Nancy Ajram. Though a woman like Nancy probably can’t be described as a marginalised voice, it’s Labaki’s casting of the glamorous Ajram that belies the former’s subversive tendencies; in one famous video for ‘Ah w Noss’, Ajram plays an Egyptian villager, hand-washing clothes on the roof while scolding a pesky stalker. In another, Labaki casts Ajram as the working-class owner of a smoky café who wipes down tables before busting out the requisite sexy dance moves. In a music video climate of glossy, inaccessible beauties, these projects were radical.

Labaki’s first feature, developed during a residency sponsored by the Cannes Film Festival, shined a light on Beirut stories that don’t make it to the front pages of newspapers. ‘Caramel’, released in 2007, fondly follows five women of various ages orbiting around a beauty salon in Beirut, with all the attendant experiences of love, disappointment, friendship, and aging that women experience in reality that are rarely depicted on screen. Labaki herself plays the radiant star, Layale. The film became the most successful Lebanese film ever, with distribution in over 40 countries and official selection at the Cannes Film Festival.

There aren’t many – or any – Middle Eastern women who have enjoyed the same level of success as Labaki in the film industry. But, Labaki insists, she’s not interested in representing anyone but herself. “I do hope that I’m not representing Arab women the wrong way, but I don’t need to be up to any level,” she says. “I don’t feel [the issue of representation] as a weight on my shoulders, never. I’m just who I am. You just have to be true to yourself and let life take care of everything else. There’s never anything over-analysed, it’s just instinct.”

Her instinct, now, is to push ‘Capharnaüm’ as far as it can go, with the goal of instigating real change in Lebanon when it comes to child labour and abuse. Despite the difficulties of working with a government like Lebanon’s, Labaki keeps the fire burning. “Hope is my fuel. If I believed that there was no hope then I would die. This is what keeps me going. I’m also betting on the humanity of people. Even in this corrupt government there are some good people who want to make a change but don’t know where or how to start. Some people think I’m naive or too ambitious and that nothing’s going to change, but what do we do? Do we just live with the problem? I don’t think this is the right way to exist in the world.”