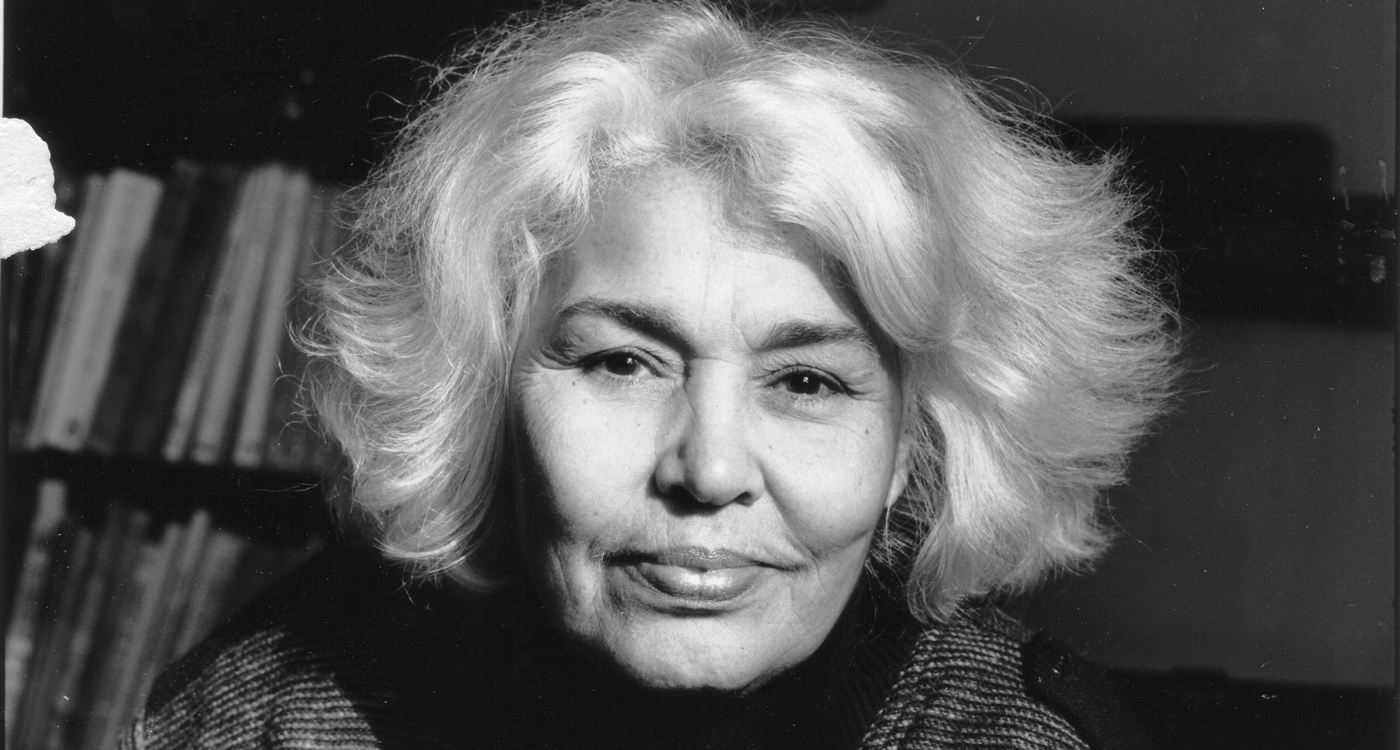

The Egyptian feminist writer, activist, physician and psychiatrist, Nawal El Saadawi, has braved prison, exile and death threats in her fight against female oppression. It’s a fight she wants to see through to the end.

The first thing Nawal El Saadawi does when we speak for the first time, is correct my use of the term Middle East.

“I’m very critical of the word,” she says in her elegant drawl. “Middle? Middle to whom? We were given the name Middle East by the British colonisers, so I never use it.”

Point taken (but with just a smidgen of embarrassment). Despite her charming laugh, the octogenarian icon is not shy of offering stern correction to points she disagrees with, which only adds to the intimidating prospect of interviewing her in the first place. She, after all, is the ultimate bastion of Arab feminism, the writer, novelist and activist who has inspired countless generations of men and women to stand against gender-based oppression and who was thrown in jail because of it.

El Saadawi was born in 1931 in Kafr Tahla, a village about an hour’s drive from the centre of Cairo. The second of nine children, she was blessed with a father she credits with being unusually progressive for his time.

A doctor by training, El Saadawi graduated from Cairo University in 1955. Although she ended up practicing psychiatry for most of her career, she was a qualified surgeon and during the 1967 war with Israel, she volunteered as a doctor in the trenches and in the Palestinian camps, an experience she has said radicalised her.

El Saadawi began writing early on, as is evident from the size of her canonical oeuvre, which spans more than 49 novels, plays, essays and memoirs. She has consistently courted outrage with her work and deals with a range of issues traditionally deemed taboo. The common thread binding all her work together is a feminist zeal and desire for social justice.

WOMEN ARE TAUGHT SINCE THEY ARE CHILDREN THAT THEY SHOULD OBEY. THEY OPPRESS THEMSELVES, BECAUSE THEY ARE OPPRESSED AND THE OPPRESSED BECOMES THE OPPRESSOR HERSELF.

“Women’s problems are universal,” she tells me, perhaps weary of being boxed in as just a feminist for Arab women. “We are one world, dominated by the same system: a capitalist, patriarchal, military, religious and racist system. If I am going to speak about women’s challenges in the Arab world or North Africa, it applies somehow, to women in the US and Europe or Asia.”

From Islamic fundamentalism to American imperialism to domestic violence and female genital mutilation (FGM), El Saadawi has done and spoken out against it all – often in quite graphic detail, which has frequently put her life in danger.

From Islamic fundamentalism to American imperialism to domestic violence and female genital mutilation (FGM), El Saadawi has done and spoken out against it all – often in quite graphic detail, which has frequently put her life in danger.

“The most difficult moment of my life, was of course when they came and broke down the door to my home and took me to prison, under Sadat,” she recalls with characteristic defiance. In 1972, she lost her job at the Egyptian Ministry of Health because her book, ‘Women and Sex’, had just been published and had ruffled too many feathers. In the book, which was banned by both political and religious authorities, El Saadawi wrote of FGM, female desire, religion and linked sexual problems to political and economic oppression, in line with her Marxist-feminist ideologies.

“My books were censored under Sadat and Mubarak,” she says of the oppressive regimes of Egypt’s former despots. “I was censored in the media – so many progressive voices in Egypt, both men and women, were silenced.”

With her increasing activism, came her eventual arrest. In 1981, then-president Anwar Sadat threw her in jail for ‘crimes against the state’. She was jailed for three months and released shortly after his assassination.

She took to prison with her typical dynamism, using her jail time to pen a memoir of her experience; ‘Memoirs From The Women’s Prison’. She wrote this on a roll of toilet paper with an eyebrow pencil, both smuggled to her by a fellow prisoner from the prostitutes’ ward. Despite her release from jail, the feminist activist remained besieged by death threats, issued by various religious groups, eager to see her eradicated from the socio-political landscape.

This led to her second “most difficult moment”: living in exile. In 1988, El Saadawi fled her homeland, fearing death. “To find your name on the death list to be killed in your own country?” she says, the outrage still seared in her memory, still present in her voice. “This was very tough. I had to fight – fight just to survive.”

She found herself in the United States, where she taught at Harvard, Duke and other prestigious universities, lecturing, rather aptly, on dissidence and creativity. She wrote prolifically during her eight-year exile in America but her work continued to be censored in her home country, just as it continues to be censored in today’s Egyptian media, she says, “because of the Muslim Brothers.”

WOMEN’S PROBLEMS ARE UNIVERSAL. WE ARE ONE WORLD, DOMINATED BY THE SAME SYSTEM: A CAPITALIST, PATRIARCHAL, MILITARY, RELIGIOUS AND RACIST SYSTEM. IF I AM GOING TO SPEAK ABOUT WOMEN’S CHALLENGES, THEY APPLY TO WOMEN EVERYWHERE.

The act of censorship for El Saadawi remains a central point of frustration. She speaks fondly of the many who have taken to her brand of activism, inspired by her dissident material. But what about ordinary men and women, as of yet unpainted by the dissident brush? How can they ever change, if they don’t have access to progressive voices?

This question comes up several times throughout our interview, as I press her on why she chose to fight on behalf of Arab women, when many choose not to fight for themselves. “Women are brainwashed,” she says. “It’s slavery. Women are taught since they are children that they should obey the man, obey the husband, obey God, they should be veiled, they should be modest and humble. Women oppress themselves, because they are oppressed and the oppressed becomes the oppressor herself. Women aren’t even aware of their rights!”

So how do you change this, if progressive women are censored? “Ordinary women,” she continues, “need to hear the voices of the progressive women.” The narrative of post-uprising nation building – particularly in Egypt – has been gendered. But look to Tawakkol Karman and her dogged fight for women’s rights in Yemen and you begin to understand the winds of change, however faint they might yet be.

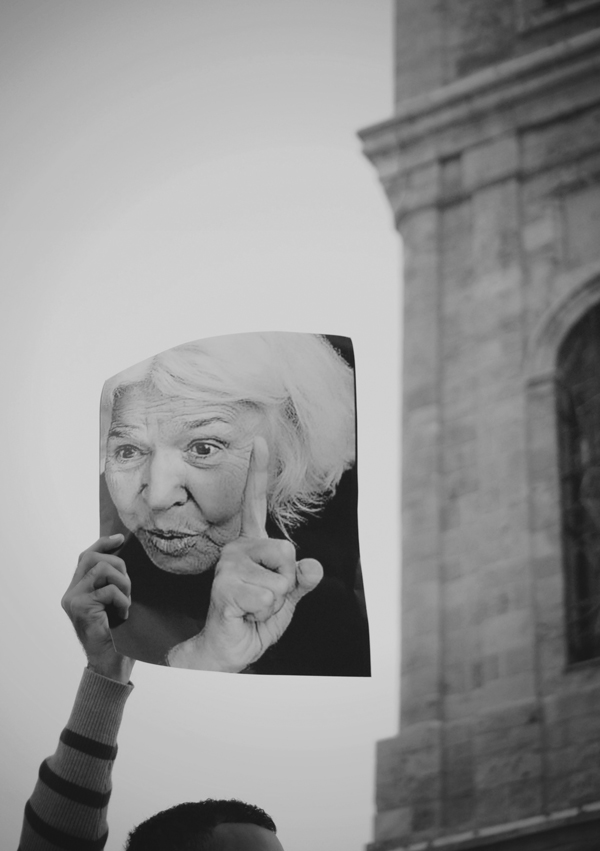

On January 25th, 2011, El Saadawi was given a golden opportunity to spread her gospel beyond her living room and its perennially revolving groups of activists and intellectuals, to ordinary Egyptian citizens. She camped day and night in Tahrir Square along with protestors decades her junior.

Once Tahrir’s initial eighteen days were over, El Saadawi immediately set about (re)establishing the Egyptian Women’s Union. The goal of the EWU is to “challenge the backlash” against Egyptian women that President Mohammad Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood have created.

“Suzanne Mubarak,” a name El Saadawi utters with pointed disdain, “banned the [original] EWU in the 1990s.” Egyptian women were left, disbanded, something she hopes will be rectified with her union.

“Women in Egypt, without unity, cannot be liberated, cannot protect their rights in the state and the family and cannot participate equal to men in their public and private lives,” the EWU’s 2011 charter stated. Today, she says, most of the EWU is made up of youth – young women and men, from different revolutionary groups. She notes that 50 per cent of the women’s union are young men, around 20 to 25 years old.

“I asked one of the young men why did you come [to join EWU]? He said, ‘I have sisters who are oppressed by my family, who force them to be veiled. I want to help my sisters challenge my parents. My sisters are afraid to join but I am the boy. I am the man. I am free. So I can join the EWU to help my sisters to be liberated.”

It is being among such progressive young thinkers, both men and women, which gives Nawal El Saadawi hope. “In spite of everything I have hope. The revolution will win. Yes. Yes. The Revolution will win.”