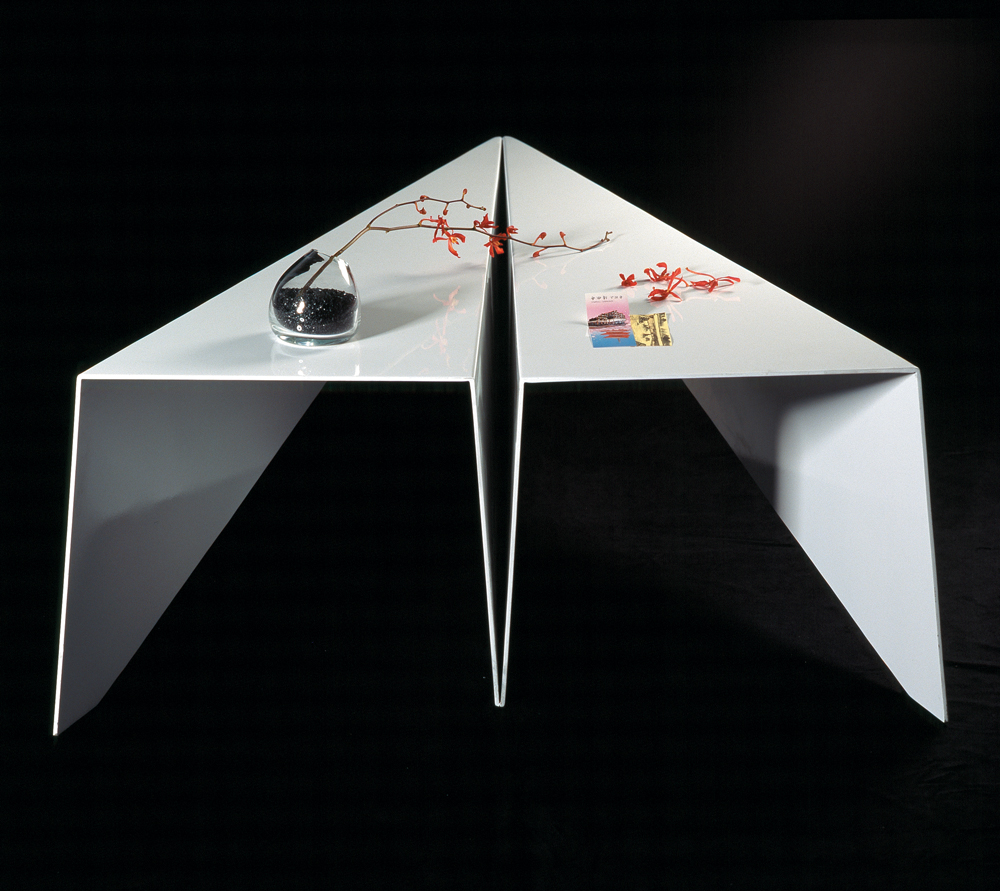

It may look like a paper aeroplane, almost split in two but this triangular coffee table is cast in metal. With a massive hand-folded sheet of aluminium, Iqar is polished to a mirror-like finish.

Bespoke speaks to vanguard designer Karen Chekerdjian about her lovingly crafted handmade objects and her influence in the design world.

There is something raw about Karen Chekerdjian’s store. There’s her logo etched into the floor that you stumble upon as you enter and the dictum facing you on the opposite wall that proclaims “things we make, things we love.” Maybe it’s the handcrafted yet industrial-looking objects in limited editions, like the tinned brass ‘flower bowls’ or the perforated fruit plates and cake trays. Then there’s the fact that her high-ceilinged studio used to be a warehouse for metal bars and in redecorating, she left some walls left untouched so the bricks remain visible through grey plaster.

Wherever this visceral element comes from, her current shop window exemplifies it: a spartan fairytale staged behind the expansive glass facade. A piece of untreated leather lies on an unevenly shaped table, with a carpet of curled wood shavings lying beneath. There’s an illustrated backdrop of Hansel and Gretel, depicted as shadowy figures against a barren-looking forest, and a real gingerbread cake studded with colourful Smarties. “It’s like kids at the very edge of the world of cruelty,” she remarks, in reference to the faintly morbid undertones of the setting.

Chekerdjian carefully runs her fingers along the table’s rough-hewn edges. “You lose a lot of substance when you cut and clean wood,” she explains. “But time does its own work, if you let it be. I wanted to work with the imperfections and the different thicknesses that were already there.” This is part of her affinity for “real materials,” fresh from nature. If you ask her how she designs, she will say that she follows her gut and the input she gets from the small team of artisans she collaborates with on projects.

Her designs weren’t always this primordial. She mentions that her work has evolved from being more conceptual to more instinctual. Her first object to be produced (a suspended system of irregularly formed hangers called Mobil, which was designed while she was studying product design at Milan’s Domus Academy) was brought out in 1999 by prestigious Italian furniture manufacturer, EDRA. In 2002, she collaborated with Icelandic artist Tinna Gunnarsdottir to create a series of spherical containers called Rolling Stones. Part of an installation exploring the nature of free objects, they were so popular that they are now on display in Copenhagen’s Design Museum.

Chekerdjian’s minimalist aesthetic now increasingly relates to the joys and pains of childhood. “Call me rebellious, but I’m against plastic toys,” she says in reference to her recently completed toy collection entitled Adam’s. Made up of Lego-like building blocks of varying colours, the idea was “to sensitize children to different forms of wood”, which are enclosed in old tin boxes, much like those the designer remembers were used to store Arabic sweets when she was a child.

It isn’t just Chekerdjian’s demeanour that is youthful, she admits that even her drawings can be mistaken for a child’s. But while her early years may serve as muse, this mother of two projects a mature vision of functionalism and beauty, of innovative domestic arrangements and the way metal can allude to, and even embody, motion.

These hints of softer matter can be found in her brass poufs, for instance, whose lattice-like lids are hand-stitched to the base with metal wires, as if they were threads. Her inspiration, she says, was the way rattan is woven into furniture. Then there’s her Cookie Paper tables, which may be made of brass, but fold in and out like pleated lampshades. “They make me think of skirts,” Chekerdjian says, a trace of mischief in her voice.

It is with this same impish flair that she devised Iqar, a triangular coffee table made from a single massive hand-folded sheet of aluminium. Divided almost completely down the middle by a huge fold, it is immediately reminiscent of paper planes. Part of the Disappearance of Objects series, Iqar was exhibited at New York’s design fair, ICFF, together with some of Chekerdjian’s other asymmetrical objects in the series, unstructured stainless steel forms polished to such a degree that they ‘disappear’ by reflecting their surroundings and give you the sense that you are missing an angle here and there.

Her bulbous Hiroshima lamp (2004), also in stainless steel draws from her fascination with the weaponry of war and its “seductive aesthetic.” When looked at from certain angles, the lampshade creates the optical illusion of floating above its base. There’s even a hint of war in her massive platform-like coffee tables in brushed brass or lacquered wood, made of differently-sized cubes clustered together to resemble rocky landscapes, which Chekerdjian thinks looks like a “futuristic warship.”

In the wider struggle against both the war-making machine and its factory counterpart, you will find that almost every object Chekerdjian designs comes with its story of humility and discovery. Inspired by pictures of old safari lodge chairs, traditionally made from bamboo, that she found in a magazine from the 1970s, Chekerdjian set out to link the animals hunted from those lodges to the chairs themselves and so the Elephant Chair was born. Using real elephant leather and beechwood, it has foreshortened stumps for legs, curved inward at the back, as if bending from the weight of its low-slung body. “When you think of an elephant,” she explains, “ a bulky image comes to mind.”

Despite the dearth of raw materials accessible to designers in Lebanon (as opposed to Italy, where “everything can be found and mass-produced”) Chekerdjian has overcome limitations by revolutionising the materials and techniques that exist. Working with local craftsmen, she tries to push her materials beyond their limits, ignoring protests by her partners, who often answered all her requests by telling her that what she wanted to do was impossible. Disregarding the constraints of her materials, if she wants to crease metal, she will and if she needs to treat a 3-sided piece of rosewood like a four-legged rectangular table, she’ll do that too. One thing about Chekerdjian’s work is certain, it will continue to challenge the rules of what’s possible in the world of design.