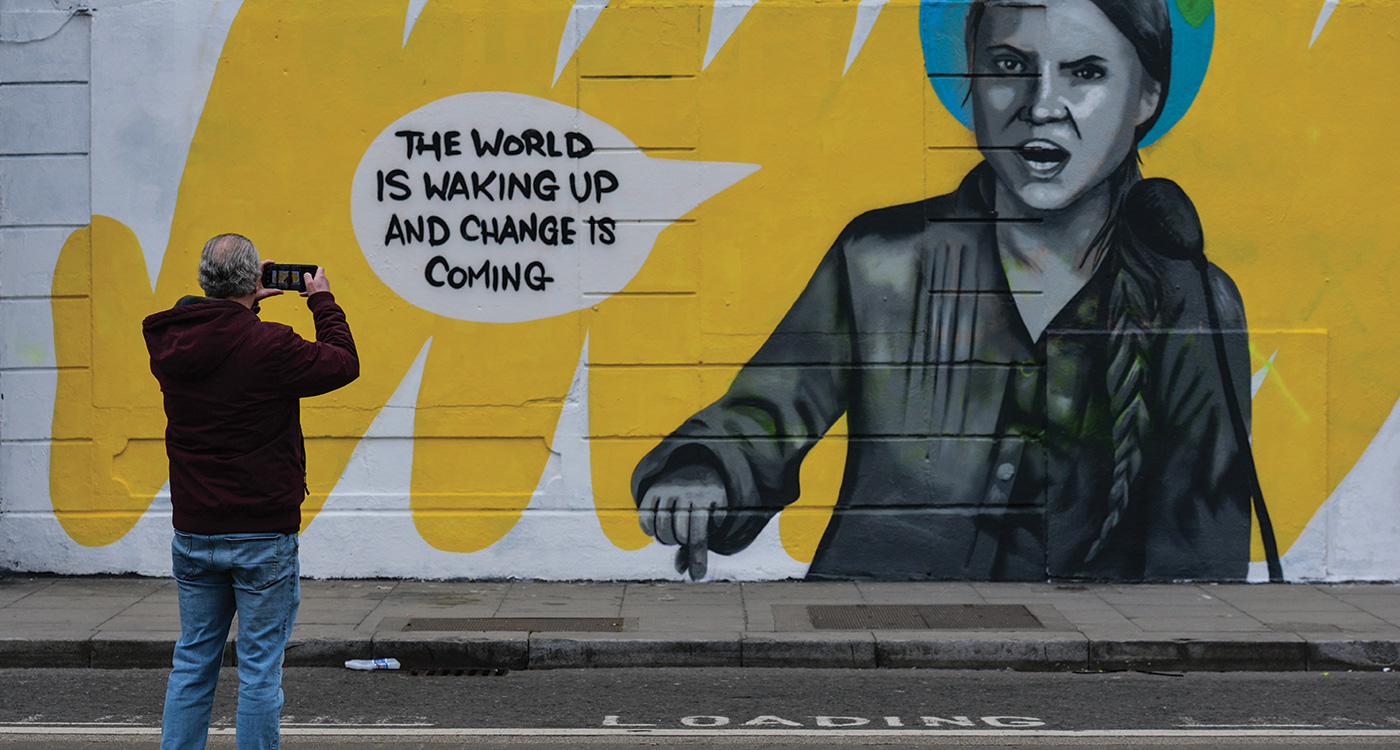

It’s crazy to think that Greta Thunberg, the Swedish environmental campaigner and pioneer of the school strike movement, is already 18. It feels like only yesterday that she appeared on the international stage – an impish 15-year-old prophet of doom telling world leaders they were stealing her future. She certainly looks more grown-up now, chatting to us over Zoom from her flat in Stockholm. “It feels very strange,” she admits, when asked about this landmark age, “but I’m not the kind of person who celebrates birthdays very much.”

Admittedly, it is that disconcerting maturity that propelled Thunberg onto the international stage, when in 2018 she began a “school strike” outside the Swedish parliament to raise awareness of the climate crisis. She was inspired by pupils in the US who had protested against gun laws after a school shooting and had tried to find others to join her, with no luck. She sat on the pavement alone in a raincoat, with a placard and an angry frown that has become quite familiar in the intervening years. Soon camera crews were interviewing her and the news spread around the world, inspiring a movement under the name ‘Fridays for Future’. In fact, in 2019 an estimated four million young people participated in climate strikes inspired by her.

Thunberg is a heroine, an icon, a role model, and an idol who is unquestionably making change happen by living what she preaches. For example, she won’t buy new clothes, doesn’t eat meat, and refuses to fly. Famously, in August 2019, she sailed across the Atlantic from Plymouth to New York, in a 60-foot, solar-powered yacht equipped with underwater turbines. She’s also now a published author, with a new book that came out last year, entitled ‘No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference’.

What’s more, environmental policies now top the political agenda, and for the first time climate change is front-page news. How much of it was driven by her? “There has been a welcome change in the way we speak about the climate crisis, it has got much more focus now than it had before. The school strike movement could have played a part in that,” she agrees. “But with every day that goes by we can see more evidence that we are in crisis.” She denies that she is the leader of anything – the movement “should not be top down”, she says, but the strikes were her idea and were startlingly effective. What better way to jolt the masses out of their complacency than by being lectured over the breakfast table by their own kids; it is hard to think of any other social movement that has been led so firmly by the young.

Thunberg is now a pin-up for the environmentally conscious, a three-time nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize (2019-2021) and a Time magazine person of the year, at a time when public discourse has never felt more toxic. She has been personally attacked by world leaders including Putin, Bolsonaro and Trump. “If you start thinking about where you are and what is being said about you and how much focus you’re getting, you would develop a self-image that wouldn’t be very sane,” she says. Instead she understands it as a tactic. “Rather than speaking about the climate crisis, they try to make this a debate about me or my personality or my appearance or my parents or my sister or whatever, so you just have to come to terms with that very early on.”

She has certainly handled it adeptly. When Trump, who took the US out of the Paris Climate Agreement, tweeted: “Greta must work on her anger management problem, then go to a good old-fashioned movie with a friend! Chill Greta, Chill!”, she updated her Twitter biography to say: “A teenager working on her anger management problem. Currently chilling and watching a good old-fashioned movie with a friend.” Then, as Trump raged over losing the presidential election, tweeting “STOP THE COUNT!”, Thunberg coolly echoed his “chill” tweet back to him. That a teenager could make presidents look foolish is a curious sign of the times. And she is under no illusions about what the election of Joe Biden will bring. “Of course, it will mean a change but just because of that shift we shouldn’t be relaxing and thinking everything is all right now.”

She is equally underwhelmed by Boris Johnson’s ten-point plan for the environment, announced with great fanfare at the end of last year. “Sure, you could see it as better than nothing, and of course everything is better than nothing, but that plan has also received a lot of criticism from the scientific community, who say that it is not enough to be in line with the Paris agreement.” And that’s the Thunberg we’ve grown to love: the headmistress grudgingly awarding her elderly pupils a C-minus for effort and telling them to try harder as she sends them out of the door. She refuses to be drawn on specific policies. “If I were to talk about taxes or green new deals then it would become a question about party politics and the climate crisis is beyond party politics,” she says. Her mantra hasn’t changed: “We need to treat the crisis like a crisis and we need to listen to the science.”

Yet, Thunberg is an accidental hero. She grew up in a middle-class family in Sweden, the daughter of an actor turned stay-at-home father, and a well-known opera singer mother. At about 11 years old she developed an eating disorder. Her parents were told to monitor everything she ate as well as the time it took for her to eat it. A typical entry reads: “Lunch: 5 gnocchi. Time: 2 hours and 10 minutes.” The psychologist at Thunberg’s school suggested that their daughter might be on the autistic spectrum but it would be years before they got a diagnosis; then she got several at once. Thunberg was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome (a high-functioning form of autism), obsessive-compulsive disorder and selective mutism. It was only then that her parents began to understand what their daughter had been going through. There is a heartbreaking passage in her mother’s book ‘Our House Is on Fire’ when her father accompanies her to the end-of-year ceremony at school and realises that the other children are openly laughing and pointing at Greta in front of him. But the diagnosis helped change all that. “It definitely helped me,” Thunberg says. “You could understand yourself better. You understand why you aren’t like the others, why I’m so socially awkward and so on.”

The school strike for climate (Skolstrejk för Klimatet), also known variously as ‘Fridays For Future’ (FFF) is an international youth movement started by Greta Thunberg. The idea is for school students to skive off classes, on select Fridays, in order to participate in demonstrations that demand climate change action from political leaders. One global strike, held last September (2020), gathered over 4 million protesters, making it the largest climate rally ever.

Clearly intelligent with a voracious appetite for facts, there are clips of Thunberg at eight or nine reciting the periodic table by heart. She has called Asperger’s her superpower and still sees the condition as a positive thing: “Some people see Asperger’s or ADHD or any of these letter combinations as something negative, but of course it doesn’t have to be – it can be something you use as an advantage.”

She started thinking seriously about climate change after a lesson in which a teacher showed a documentary about the island of plastic floating in the Pacific. Thunberg started to cry. Others in the class were distressed too, but they moved on when the school bell rang. Thunberg could not. It has been pointed out that people with autism are overrepresented within the climate movement and I’m interested to know why she thinks this is. “Humans are social animals. We copy each other’s behaviour, so if everyone else is acting as though there’s no crisis then it can’t be that bad. But we who have autism, for instance, we don’t follow social codes, we don’t copy each other’s behaviour, we have our own behaviour,” she says. “It’s like the tale of The Emperor’s New Clothes; the child who doesn’t care about his reputation or becoming unpopular or being ridiculed is the only one who dares to question this lie that everyone else just silently accepts.”

Over the years there has been a lot of speculation about the influence her parents have over her profile and her campaigning, but it is very clear when you talk to her that Thunberg thinks for herself. And she’s convinced that her fame is going to end as abruptly as it began. “I think it is very strange that this attention and focus has stayed for so long. I won’t have this platform for long, so that’s why I’m trying to do as much as I can to use my position, or whatever it is, to do what I can in this limited amount of time,” she says.

She also confirms that she writes all her own speeches and delivers them as she chooses. But what about those tears, the visceral swell of emotion that makes white-haired politicians squirm and the rest of us wish she wouldn’t take life so seriously: Does climate change really hurt her that much? “No, of course not, people think I’m depressed but those are just metaphors to get people’s attention. Of course, I don’t think about the climate like that, I don’t sit and speculate about how the future might turn out, I see no use in doing that.” I’m digesting this bombshell when she continues: “As long as you are doing everything you can now, you can’t let yourself become depressed or anxious.”

She is decidedly laid-back about other people’s choices too. I ask what she makes of celebrities who talk about the environment while flying around the world. “I don’t care but there is a risk when you are vocal about these things and don’t practise as you preach, then you will become criticised for that and what you are saying won’t be taken seriously.” Nor does she agree that having children is bad for the planet. The whole issue is a distraction, she says, and one that scares people away. “I don’t think it’s selfish to have children. It is not the people who are the problem, it is our behaviour.” But her own choices demonstrate what she believes is the right way to live. She stopped flying years ago – she famously sailed to America to speak at the 2019 UN climate summit. She is a vegan and has stopped “consuming things”. What does that mean, I ask. Clothes? She nods. What if she needs something? “The worst-case scenario I guess I’ll buy second-hand, but I don’t need new clothes. I know people who have clothes, so I would ask them if I could borrow them or if they have something, they don’t need any more,” she says. “I don’t need to fly to Thailand to be happy. I don’t need to buy clothes, so I don’t see it as a sacrifice.”

Thunberg’s quiet puritanism is effective. It certainly seems to have worked on the people around her. Her mother’s international career ended in 2016 when she decided to stop flying too. None of the other young activists in the school strike movement fly, she says, they are used to communicating on Zoom: “So when the pandemic hit, we already had methods to communicate online.”

She took a year’s sabbatical to travel and has two more years of school before she needs to make decisions about university. “I wanted to study natural sciences, but then I thought maybe where I will be most useful is in another direction, like policies.” She may still change her mind, she says. “My life is so strange and things are changing constantly, so it’s hard to plan anything.”

How will she know when she has done as much as she can and is free to move on? “That’s difficult with the climate crisis because it’s such a complex issue. Even though I say in speeches that it’s black-and-white, of course it’s not black-and-white, there is no magic number that we can surpass.”

Photography: Artur Widak