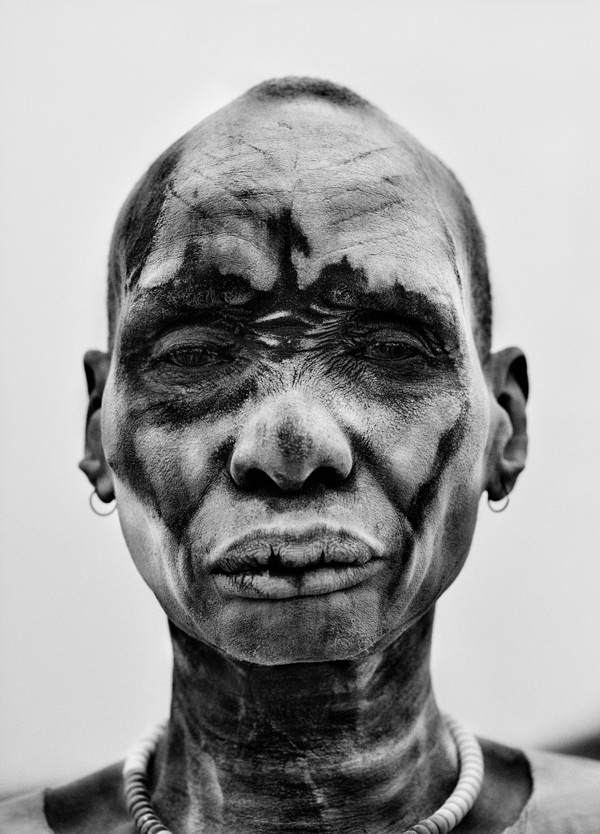

Sebastião Salgado’s journeys have taken him to the farthest reaches and most remote communities of the planet and the photographs he’s brought back tell tales of humanity in all its wonder. With his latest book ‘Genesis’, the Brazilian photographer presents an intimate portrait of our world.

The first glimpse of Sebastião Salgado’s eyes is striking. Crystal blue, they transfix, seeming to swim with the tales etched into their gaze.

Amazonas, his Paris-based agency, is housed in an office facing the Canal Saint Martin. As I enter, Salgado greets me with a warm, weathered regard that has clearly witnessed the modern world at close quarters, in all its harshness and splendour. The studio is spacious, its façade covered with windows that stretch from floor to ceiling. Towering wooden cabinets, built to hold decades of work, run along the far wall.

Amazonas, his Paris-based agency, is housed in an office facing the Canal Saint Martin. As I enter, Salgado greets me with a warm, weathered regard that has clearly witnessed the modern world at close quarters, in all its harshness and splendour. The studio is spacious, its façade covered with windows that stretch from floor to ceiling. Towering wooden cabinets, built to hold decades of work, run along the far wall.

Building plans for the Ara Pacis Museum in Rome are strewn across the table to my right. He points out the interior installation models that accompany them. “This is my wife’s work,” he says, proudly. “She plans all of my exhibitions and designs all my books.” Intimacy is a key component in Salgado’s work, whether as manifest in his collaboration with loved ones or in his insistence on photographing his subjects in some of the harshest environments known to humankind. He admits that he thrives on this human contact.

Salgado has explored humanitarian issues for decades, documenting famine, war and catastrophic cruelty. During those years, he developed an understanding of the people he photographed, a connection that shines through all of his work. He became known for his humane and intimate style.

Born in Brazil, the photographer spent his youth in a rapidly transforming country, once referred to as part of the Third World and today, an emerging global economic power. Salgado’s origins have given him a deep understanding of the instability created by development and the consequences projected by its hurtling advances. He has travelled the world as economist and photographer, capturing humanity’s gift for splendour and atrocity on every continent.

“I am a person who was born in the Third World, who grew up in the Third World. My country now is a developing country but was an underdeveloped country for many years,” he explains, underlining sentiments he has clearly considered before. “When I went to photograph some of these regions, it was like I was in my home, like it was my place. Even if it wasn’t my country, I was in a context that I knew. The problems were similar and we were inside the same level of comprehension and of feelings.”

For the viewer of photographs, it can be fundamentally perplexing – nauseating, even – to gaze into the eyes of the suffering. For a photographer, the attempt to capture moments of chaos, conflict and the all-too-human consequences of inhumanity can be ethically and morally destabilising. Nonetheless, Salgado’s images act as witness to realities that, without photography, might easily be ignored by an oblivious world.

His lens isn’t focused on representing distress and misery as isolated conditions. Submerged in the chaos of political and natural upheaval, he strives to depict the binding quintessence of community in the grandest sense: the dignity and mutual respect we each own as a birthright. “Everyone I photographed was part of a larger community. If they were dying because they lacked material resources, they were dying inside of a larger group. There were people crying for them, protecting them, until the last minute.”

The stories of Salgado’s subjects became his story and his work drew closer, infinitely closer, to his soul. After decades of bearing witness to genocide, famine and forced migration, he set aside his camera and gave up his art, his faith in humanity deeply disturbed.

“Those people,” he continues, talking of his former subjects, “have a strong sense of dignity and personality. Many people thought they were in misery. They were never in misery. Misery is another thing. Misery is isolation from your fellow humans. To not be part of a society.”

Salgado recently completed an 8-year project entitled ‘Genesis’. It is one of the first large-scale projects he has produced since that rupture. The book is the culmination of his life’s process, a return to the essence of nature and how man fits into it. The images captured, the miles travelled and the years spent on the ground making ‘Genesis’ are, in a sense, the manifestation of one man’s rekindled hope for humanity.

Salgado recently completed an 8-year project entitled ‘Genesis’. It is one of the first large-scale projects he has produced since that rupture. The book is the culmination of his life’s process, a return to the essence of nature and how man fits into it. The images captured, the miles travelled and the years spent on the ground making ‘Genesis’ are, in a sense, the manifestation of one man’s rekindled hope for humanity.

“These things that I photograph are what is pristine in this planet and we must protect them in order for them to remain,” he says, his voice building with a sense of urgency, “and we must rebuild at least part of the things that we have destroyed.”

And so Salgado sought out communities scattered around the globe that have escaped the tangling coils of modernity. From the Indians of the tropical Amazonian rainforests in Brazil, to the nomadic Arctic tribes of the northern-most reaches of Siberia, the photographer tracked humanity to its remotest homes. He lived with his subjects in their tepees and hunted with them using their bows and arrows. Each trip lasted two months. The proximity and intimacy clearly expressed in his record of his journeys is of the kind that can only spring of well-nurtured and mutual trust.

He leaves his seat and motions me toward a mammoth book lying on the table nearby. Genesis will be produced by Taschen, the German artbook publishers, who are renowned for their quality and artistic regard. All but overwhelming the table, the book is presented like a handwritten Bible, bound with minute precision, its contents selected as carefully as a museum exhibition.

Salgado runs his fingertips across the pages, which are printed in strikingly nuanced hues of grey, full of deep shadows and floating expanses of white. The volume has become a faithful portfolio of his journeys: a masterpiece in itself that the photographer is evidently proud to include among his work. The grandeur of this collection is well suited to his all-encompassing mission:

“A work can become an artwork but to become an artwork, it must be long-term and become representative of a historical moment that we live… I did this because it was my life,” he says, turning the pages of ‘Genesis’, smiling, sometimes murmuring a word or something incomprehensible that means nothing to me but which to him, must be triggered by memories of each cherished encounter captured here. “Photography has an incredible power. It is a powerful language.”

Salgado stops at a page depicting an Arctic landscape that is the home of the Nenet in northern Siberia. Nomads, following the routes they’ve traced across the ice for thousands of years, surviving on raw fish and reindeer blood, the Nenet are steadfast in their fight to preserve their language and traditions.

The tribe define Minimalist. Herding reindeer and living in the tundra during the harshest of winter months, they own only what can be carried on their back, or heaped on the dogsled. The dark forms of men and women stand out against pristine white, as some unpack their immense sleds and others construct their tepees for the night. Animal skins lie on the frozen ground, their sleds sit further in the distance. A sense of order and organisation reigns over the scene. Salgado smiles. “I learned with these guys the meaning of the word ‘essential’. They can only take what they can put inside the sled. If I give them a gift they will not take it because they can’t carry it.”

These communities represent a luminous renaissance for the photographer. In an effort to preserve our sacred bond with nature, Sebastião Salgado has sought out the last pristine swathes of it that remain for us to inherit, photographing them, preserving them, creating ties with the communities that live in them and who still haven’t forgotten what is most crucial to our existence.

‘Genesis’ is an ode to our origins and an optimistic perspective of our world and all its natural glory, an intimate portrait and an unmissable opportunity to see, in a million shades of black, white and grey, the possibilities, the people and the places that most of us never even knew existed.