Harley Davidson motorbikes have spawned generations of devotees, even producing a cult in Lebanon. Habib Battah traces the journey travelled by the bike brand from being the favourite of Lebanon’s police force to being banned by major capitals in the region.

A muscular bald man with a blondish goatee hunkers over the steel frame of an unfinished motorcycle. Amid the clanging of his cluttered metal shop, the gregarious 39-year-old describes his proudest achievement to date: rebuilding a 1977 gold-plated Harley Davidson. The scene may be reminiscent of the reality television series, American Chopper but the hulky protagonist is not Paul Teutal, the show’s hot headed host, but rather Charlie Khalil tinkering away in the Lebanese coastal town of Jounieh. He is one of around 100 proud members of the country’s Harley Davidson club which enjoys a rich Harley heritage stretching back to the 1930s.

Indeed the American motorcycle manufacturer, which has been making the much sought-after bikes for over a century, is just as much a producer of culture as it machines. A former kickboxing champion, Khalil is perhaps an extreme example of that trend.

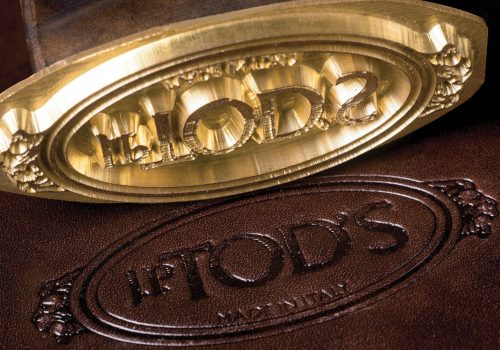

In addition to the gold-plated Electra Glide, a once dilapidated police bike which lies on display in his living room, Khalil rolls out another completely restored 1977 model from his garage adorned with an extensive array of chrome skulls. But that’s just the beginning. His closet is brimming with Harley T-shirts and black leather vests. Many are decorated with an assortment of pins which Khalil proudly explains were gifts from fellow riders befriended during major Harley events that have taken place across the Middle East in recent years. Harley memorabilia lurks ubiquitous throughout his apartment; Harley matchbox cars and coffee mugs; a Harley telephone and tea kettle, even Harley kitchen cabinets with glass cupboards designed to bear the emblematic bar and shield logo.

For Khalil, the brand is central to his life and his livelihood. While running a small aluminum business out of the basement of his apartment building, he’s restored twelve 1970s era models and built three from scratch, all retired bikes from the Lebanese police, one of the oldest Harley consumers in the Middle East. But he shrugs off any comparison to the reality show. “They just take the engine out of the box, four screws and that’s it. For me,” he adds with religious-like conviction, “it’s completely different.”

For Khalil, the brand is central to his life and his livelihood. While running a small aluminum business out of the basement of his apartment building, he’s restored twelve 1970s era models and built three from scratch, all retired bikes from the Lebanese police, one of the oldest Harley consumers in the Middle East. But he shrugs off any comparison to the reality show. “They just take the engine out of the box, four screws and that’s it. For me,” he adds with religious-like conviction, “it’s completely different.”

An obsession? Perhaps; yet Khalil’s passion for everything Harley is evident among many of the company’s customers, where buying a bike becomes the beginning of a broader addiction. Marwan Tarraf, owner of five Harleys, would know.

“Without noticing, you find yourself wearing Harley clothing,” he says, speaking from the underground garage of a new bike shop he is getting ready to open on a busy Beirut intersection. He is surrounded by over a dozen sparkling new motorcycles ranging in price from 15,000 USD – 60,000 USD. Tarraf, a film producer, is also vice president of the Lebanese Harley Club and professes a seemingly encyclopedic knowledge of the bikes as well as the inevitable catch phrases that surround them. Harley owners are typically over 30 years old, he says; “people who have worked and achieved.” In fact, many rarely ride outside of special gatherings or other occasions. “It’s not a bike you ride everyday,” he adds; enthusiasts often occupy themselves with engine upgrades or purchasing accessories while the actual bikes are “hidden not ridden.” Tarraf even stores his most prized ride, a limited-edition 100th anniversary Screaming Eagle model, in a special oxygen tent for preservation. “It’s cleaner than the air that we breathe,” he explains with a wry smile. “Maybe they are not better than other motorcycles but it’s the only motorcycle connected to a culture.” Unfortunately politicians in many Arab countries have not always made it convenient to foster that culture.

In Lebanon, motorcyclists were faced with a series of regulations beginning in the late 1990s including special registration, periodic bans and curfews on night riding. Authorities blamed the move on a surge in purse snatchings at the time, but many Harley riders complained that laws were being applied haphazardly and that they were being unfairly punished for crimes committed by others, especially small-time criminals on cheap scooters or groups of young speed bikers notorious for racing and stunt riding on Lebanon’s highways in the early hours of the morning. As a result of circumstance, Lebanese Harley lovers suddenly found themselves waiting in long lines for new permits and although the tiny Mediterranean nation boasts a plethora of scenic mountain roads ideal for cruising, cross country travel become increasingly difficult.

In Lebanon, motorcyclists were faced with a series of regulations beginning in the late 1990s including special registration, periodic bans and curfews on night riding. Authorities blamed the move on a surge in purse snatchings at the time, but many Harley riders complained that laws were being applied haphazardly and that they were being unfairly punished for crimes committed by others, especially small-time criminals on cheap scooters or groups of young speed bikers notorious for racing and stunt riding on Lebanon’s highways in the early hours of the morning. As a result of circumstance, Lebanese Harley lovers suddenly found themselves waiting in long lines for new permits and although the tiny Mediterranean nation boasts a plethora of scenic mountain roads ideal for cruising, cross country travel become increasingly difficult.

“It was a mess to drive a bike,” says Rafle Khoury, whose grandfather imported the first Harley to Lebanon in 1936. The Harley dealership remained in his family for decades until he sold it off in 2004 due to what he says was a slowing economy compounded by overbearing government regulations. According to Khoury, movement across the south of Lebanon became nearly impossible when motorcycles were completely banned in the southern town of Sidon following the assassination of four judges there in 1999. The assailants were believed to have escaped the crime scene on motorbikes. “It’s a good thing they didn’t use cars,” Khoury quips, “or else they would have banned cars in the country.”

Blanket legislation also took effect in Jordan following a fatal accident witnessed by a member of the Royal family, say local Harley owners. And in neighbouring Syria, as is the trend in the Hashemite Kingdom, Harley owners may exist but they tend to be very close to the leadership or connected to government officials. A trip to visit the late King Hussein, an avid Harley owner, was telling in that most of his companion riders were armed, Khoury says.

But ‘average’ Harley riders do exist across the Arab world. There is particularly strong growth in the Gulf countries, where up to 200 Harley bikes are sold per year in places like the UAE and Saudi Arabia, according to Khoury, although he warns that at least half of consumption is to expatriates. But in Lebanon annual sales have fallen from a peak of 40 bikes per year in the late 1990s down to around a dozen today, he adds. Things did seem to be looking up in 2005 however, when much of the curfews and permit requirements were finally lifted. It was then that Tarraf became excited about re-opening a Harley shop in the country, despite some of the political turmoil that had begun to materialize shortly after the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Al Hariri. And even as the security situation fluctuated, he had planned a major group ride to the south with about 40 riders last summer.

For Tarraf and others, Lebanon, with its picturesque geography and moderate climate, is one of the best locations in the world for Harley riding. “It’s the only place you can ride 300 days per year,” he says. Unfortunately political factors are not as forgiving as the weather, and as the clouds of war began to gather last summer, the trip to the South was scrapped. In fact, over the last two years many local Harley enthusiasts have kept their bikes locked up, weary, like most Lebanese, about stability and more immediate concerns.

“The country is not in the mood,” says Khoury, who hasn’t ridden in six months. Moments later he is interrupted by a phone call from a fellow rider inquiring about necessary straps to latch on to his bike in order to truck it to a Gulf country. The sombre mood among Lebanese Harley owners is perhaps best captured by one of the country’s most prominent politicians, Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, a statesman with a reputation for wearing blue jeans and riding bikes.

Holed up in his mountain compound, Jumblatt says fears over an assassination attempt on his life have severely restricted his mobility and thus he no longer drives his own car, let alone the Harley. “It’s been more than two or three years I’m not riding,” he says, visibly distraught and unsure if he’ll ever be taking out his bike again. Ironically, Jumblatt, clearly distracted by political developments in the country, could probably use a ride now more than ever. “It gives you some sense of relaxation to be alone, to have ride at summer time at night sometimes. I can’t now because of the security situation,” he says with a heavy sigh.

Holed up in his mountain compound, Jumblatt says fears over an assassination attempt on his life have severely restricted his mobility and thus he no longer drives his own car, let alone the Harley. “It’s been more than two or three years I’m not riding,” he says, visibly distraught and unsure if he’ll ever be taking out his bike again. Ironically, Jumblatt, clearly distracted by political developments in the country, could probably use a ride now more than ever. “It gives you some sense of relaxation to be alone, to have ride at summer time at night sometimes. I can’t now because of the security situation,” he says with a heavy sigh.

Yet in spite of all the drama, 50 shiny new Harley models were imported to the country a few months after the end of the war with Israel last summer. The client was one of the oldest Harley customers in the Middle East: the Lebanese police, known as the ISF or Internal Security Forces. According to General Lahoud Tannoury, head of the ISF’s vehicle repairs division, the Lebanese police received their first shipment of nine Harley Davidson’s in 1946, many featuring a classic side car. Tannoury says the most recent shipment of bikes, a donation from the UAE government, brings the force’s total number of Harleys to just over 300, compared to around 180 other bikes of various other Japanese makes in the fleet. He touts Harleys’ sturdiness and durability, ideal for rugged use and mountain ascents. Plus, “it has protection if it falls,” Tannoury explains, noting that most street bikes will tip all the way over at a 90 degree angle, whereas a Harley with its bulky side wings remains higher off the ground even when lying on its side. Harley culture is clearly imbedded across Lebanon’s motor police brigades with officers seemingly excited to get their hands on the new bikes, all 2006 Road King models measuring in at 1,400 cubic centimetres in engine size.

There is even a bit of Harley folklore in the air at the crumbling colonial era ISF repair station located in Beirut neighbourhood of Gemmayzeh. Many say that one of their own, a young mechanic of Armenian descent, was so skilled in Harley work that he was hired on at the company’s headquarters in Milwaukee, Wisconsin when visiting the US as part of a training workshop. Whether or not there is shred of Lebanese influence somewhere among the molten steel plants of the Midwest, the devotion to Harleys seems somehow resilient here, despite the series of national tragedies.

Even though Tarraf is not very optimistic about turning a profit at his sleek new shop, he says the project is just as important as a relief effort to supply parts and services to fellow riders.

“I don’t think it will be a good business,” he muses. “Maybe, it would if you’re living in a stable country.” Tarraf’s stream of anecdotal tales never seems to run dry, even as he walks me to the elevator shaft used both to transport bikes and visitors to the showroom level. “I know guys who make 400 USD a month and have two kids. They really can’t afford a Harley but they have one anyway.” The rationale? “If you can’t hear it before you see it, why bother?”